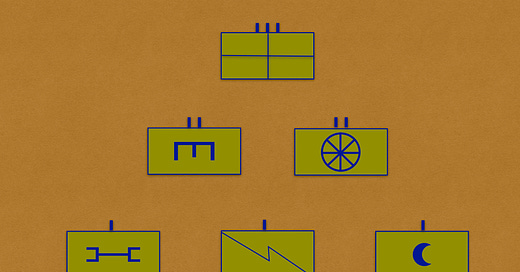

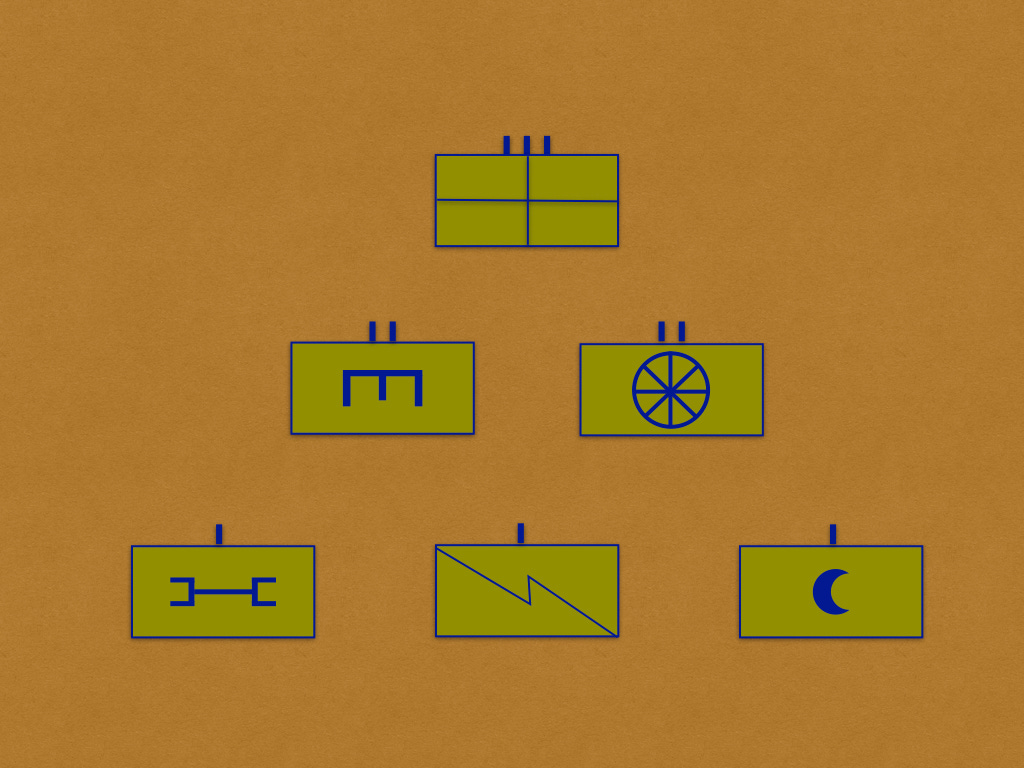

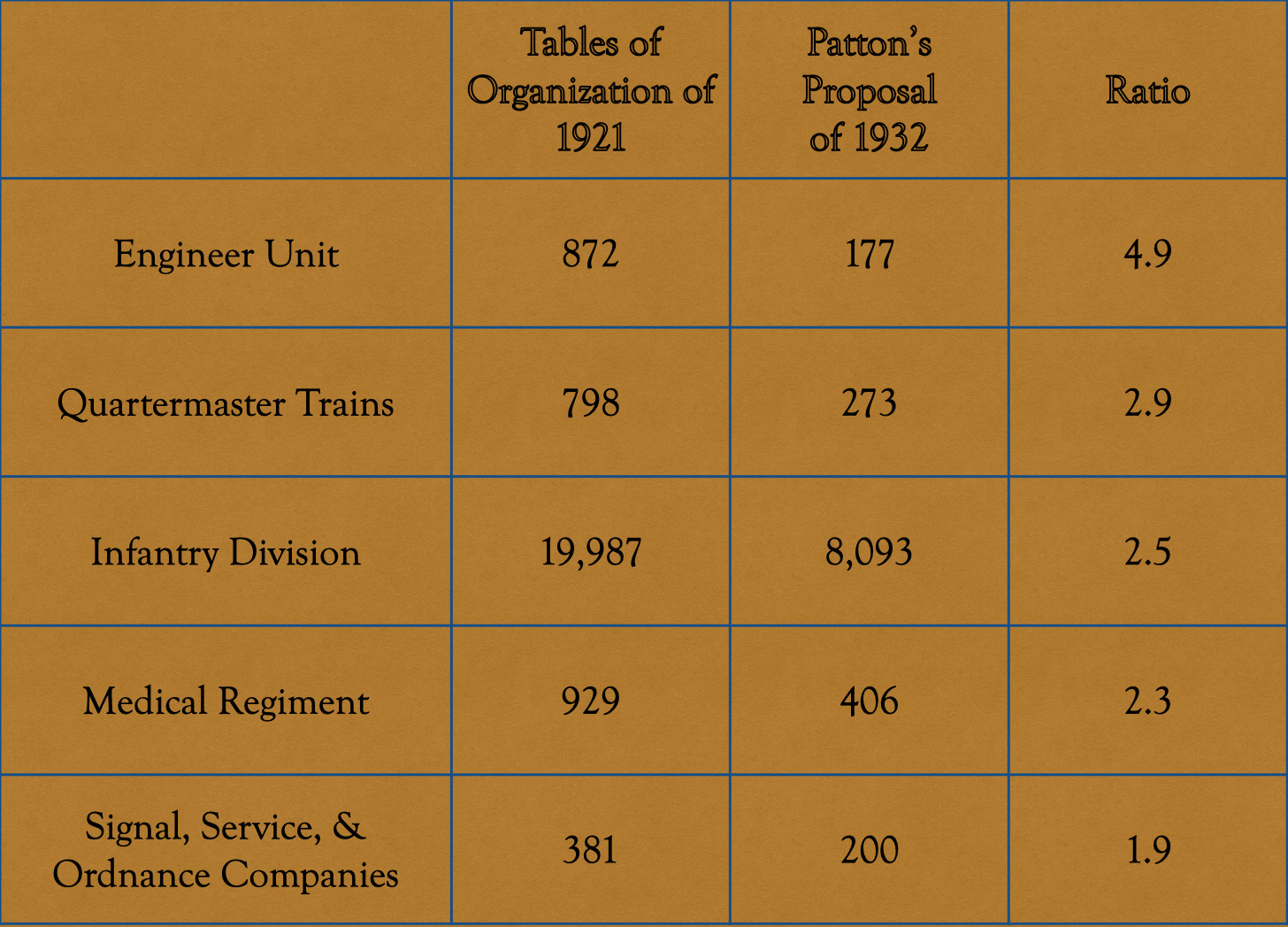

The combatant units that Major Patton included in the infantry division he designed in 1932 differed considerably, in conception as well as size, from the ones that the interwar US Army of that year planned to form in the event of mobilization. The structure of the organizations that provided support and services to those fighting outfits, however, owed much to the latter set of establishments, which had been in force since 1921.1 Indeed, the logistics elements of Patton’s ideal infantry division might well be described as smaller versions of their official counterparts.

The reduction in the size of service and support units did not, however, reflect the reduction in the size of the infantry division as a whole. In some cases, such as those of the medical regiment, the signal company, service company and ordnance company, the units in question shrank less than proportionality would have predicted.2 In other instances, such as those of the engineer element and the quartermaster train, the loss was greater than it would have been if Major Patton had followed a policy of “fair shares for all.”

Major Patton declined to provide explanations for the changes he made to the structure of service and support units. Nonetheless, the justifications he provides for his designs for both combat units and the division as a while sheds some light on his thinking. In particular, the substantial shrinkage suffered by sappers accords with Patton’s desire to avoid position warfare. Likewise, the disproportionate reduction in the size of the quartermaster trains (and thus the number of supply trucks in the division) seems to reflect his assumption that a formation that preferred rapid movement to sustained bombardment would consume less in the way of artillery ammunition.

The modest changes to the service company, which made meals for members of units too small to run their own messes, tally with both the drastic reduction in the overall strength of the infantry division and the increase in the number of battalions. Thus, while all companies and battalions of the infantry division of 1921 but one (the division air service) belonged to a unit of regimental size, the division designed by Major Patton possessed six autonomous battalions and one independent company.3

In much the same way, the increase in the number of armored fighting vehicles (from 24 tanks to 39 tanks and 5 armored cars) and the motorization of field artillery batteries seems to have counter-balanced the decrease in the work-load of the ordnance company that resulted from the reduction in the total number of artillery pieces, infantry weapons, horse-drawn vehicles, and cargo trucks worked by Major Patton.4

The size of the signal company also seems to stem from the interplay of two opposing forces. On the one hand, the presence of so many independent battalions increased the number of commanders who reported directly to the commanding general of the division as a whole. On the other hand, the aforementioned aversion to position warfare reduced the need for soldiers who specialized in the creation and care of wire-based communications networks.

Sources:

George S. Patton, Jr The Probable Characteristics of the Next War and the Organization, Tactics, and Equipment Necessary to Meet Them (Washington, DC: Army War College, 1932)

John B. Wilson Maneuver and Firepower: The Evolution of Divisions and Separate Brigades (Washington, DC: Center for Military History, 1998)

US Army General Service Schools Tables of Organization: Infantry and Cavalry Divisions (Fort Leavenworth: General Service Schools Press, 1921)

For Further Reading;

For a quick overview of the infantry division of 1921, see the article on the subject that was published in the first (ink-and-paper) incarnation of The Tactical Notebook in June of 1992.

In Major Patton’s ideal infantry division, the term “special troops” described a battalion in all but name that consisted of a signal company, an ordnance company, and a service company. In the infantry division of 1921, the same name was applied to a unit of regimental size that, in addition to companies of the aforementioned types, possessed a tank company, a military police company, and the division headquarters company. Thus, rather than comparing the special troops units of the two divisions, the chart compares the combined strengths of their signal, ordnance, and service companies.

The regiments of the infantry division of 1921 were the four infantry regiments, the two field artillery regiments, the engineer regiment, the medical regiment, the quartermaster trains, and the special troops. The autonomous battalions of Major Patton’s ideal division were the tank battalion, the cavalry squadron, the air service, the engineer battalion, the quartermaster trains, and the special troops. The independent company was the division headquarters company.

This may be the longest sentence I have written in a decade. Mark Twain would probably have said that this came from reading too many German books.

Clearly Major Patton envisioned sustainment troops with more arms and legs than normal soldiers or perhaps they were not allowed to sleep? Alternatively, he might have assumed that nothing would ever break and that no enemy, who does get a vote BTW, or strategic situation, would ever force his ideal Division into positional warfare. This service and support structure is even less robust than the old US Light Division concept of the 1980s, which was great for strategic mobility, but not so good for endurance during combat operations.

One wonders if Major Patton had heard of tactical radios at all. I know they were AM only at this point, as FM communications were not developed until 1933, but they did have portable radio transmitters and receivers by this point, so the small size of the signal unit is very bad.

Redo!

“This may be the longest sentence I have written in a decade. Mark Twain would probably have said that this came from reading too many German books.” 🤣🤣🤣

However, it is a very clear one.