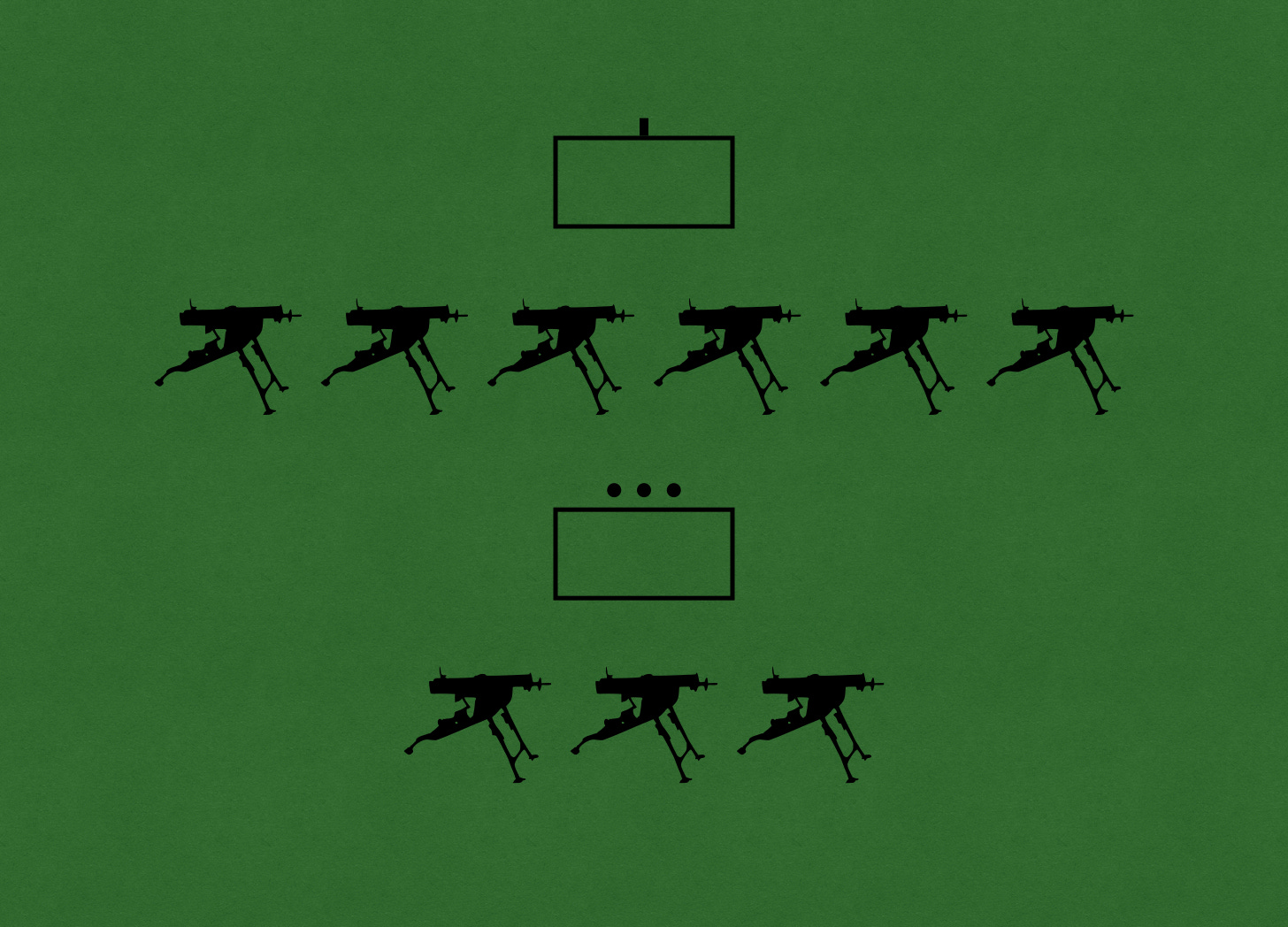

At the start of the First World War, all the machine guns assigned to a typical German infantry regiment belonged to the regimental machine gun company. Numbered as the thirteenth company of its parent organization, this unit fielded three platoons, each of which was armed with a pair of sled-mounted Maxim guns. In addition to these fully crewed weapons, the company also rated a seventh machine gun, which traveled with the baggage train as a spare.

In the course of the first year of the war, the war ministries of the German Empire reinforced the regimental machine gun companies with several hundred ‘field machine gun platoons’ [Feld-Maschinengewehr Züge]. Commanded by a lieutenant, each of these modules employed three machine guns of the aforementioned type.

I have yet to find an explanation for the third machine gun in each field machine gun platoon. As it was provided with the same sort of crew as the other two bullet-spitters in the organization, it cannot have been a spare. Thus, I find myself imagining that someone in Berlin divided the number of available machine guns by the number of available lieutenants. (I cannot say that this actually happened. However, if the archival documents I have perused over the decades are any indication, such adventures in arithmetic appealed greatly to folks who wielded pencils in the war ministries of the age of steel and steam.)

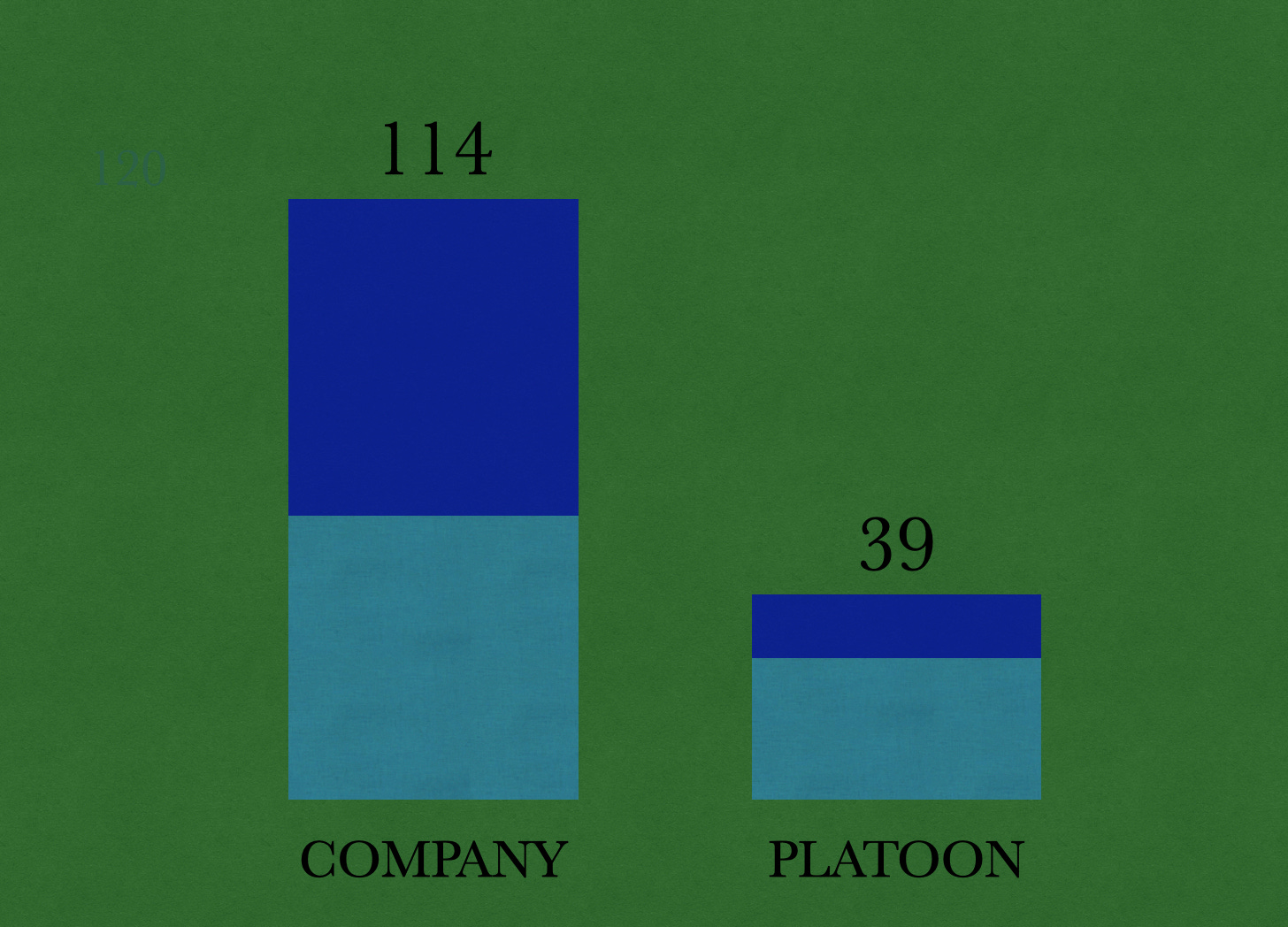

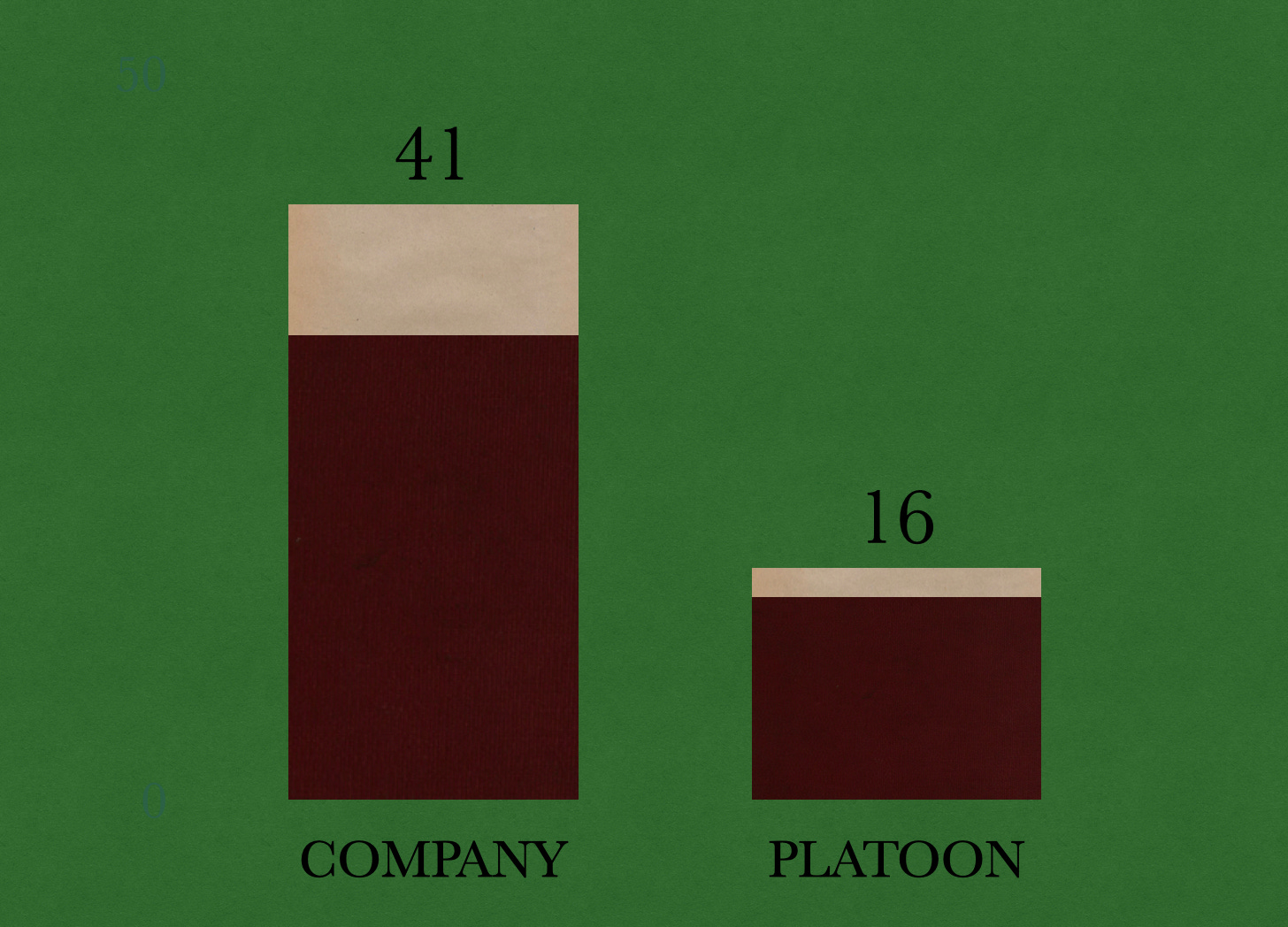

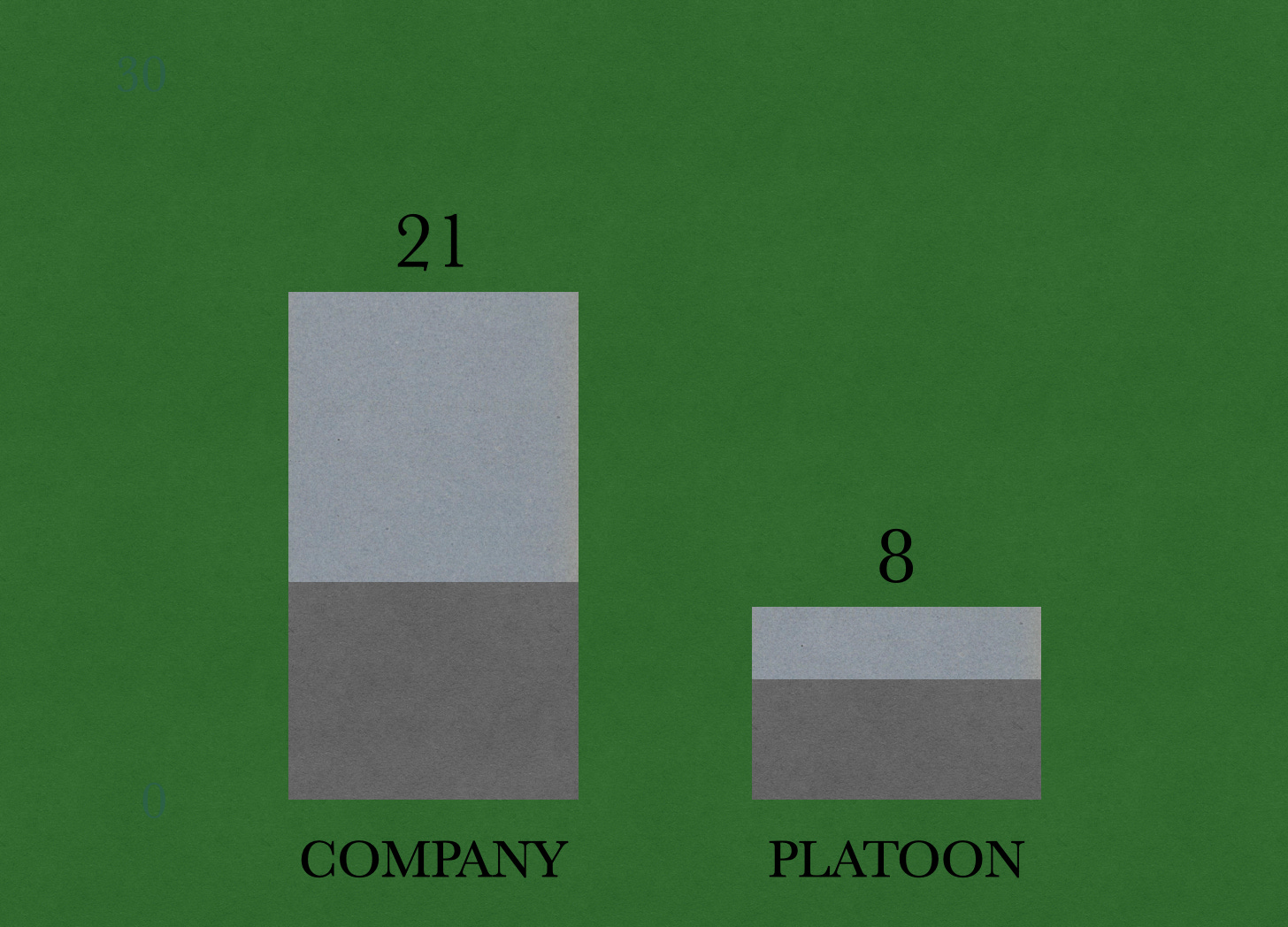

Arithmetic also suggests that the field machine gun platoons should have resembled machine gun companies that had been cut in half. That, however, was not the case. Rather, the relatively large overhead of the six-gun machine gun company - that is, the men who did things other than hump, hide, feed, or fire machine guns - meant that it was much more than twice as large as a three-gun field machine gun platoon.

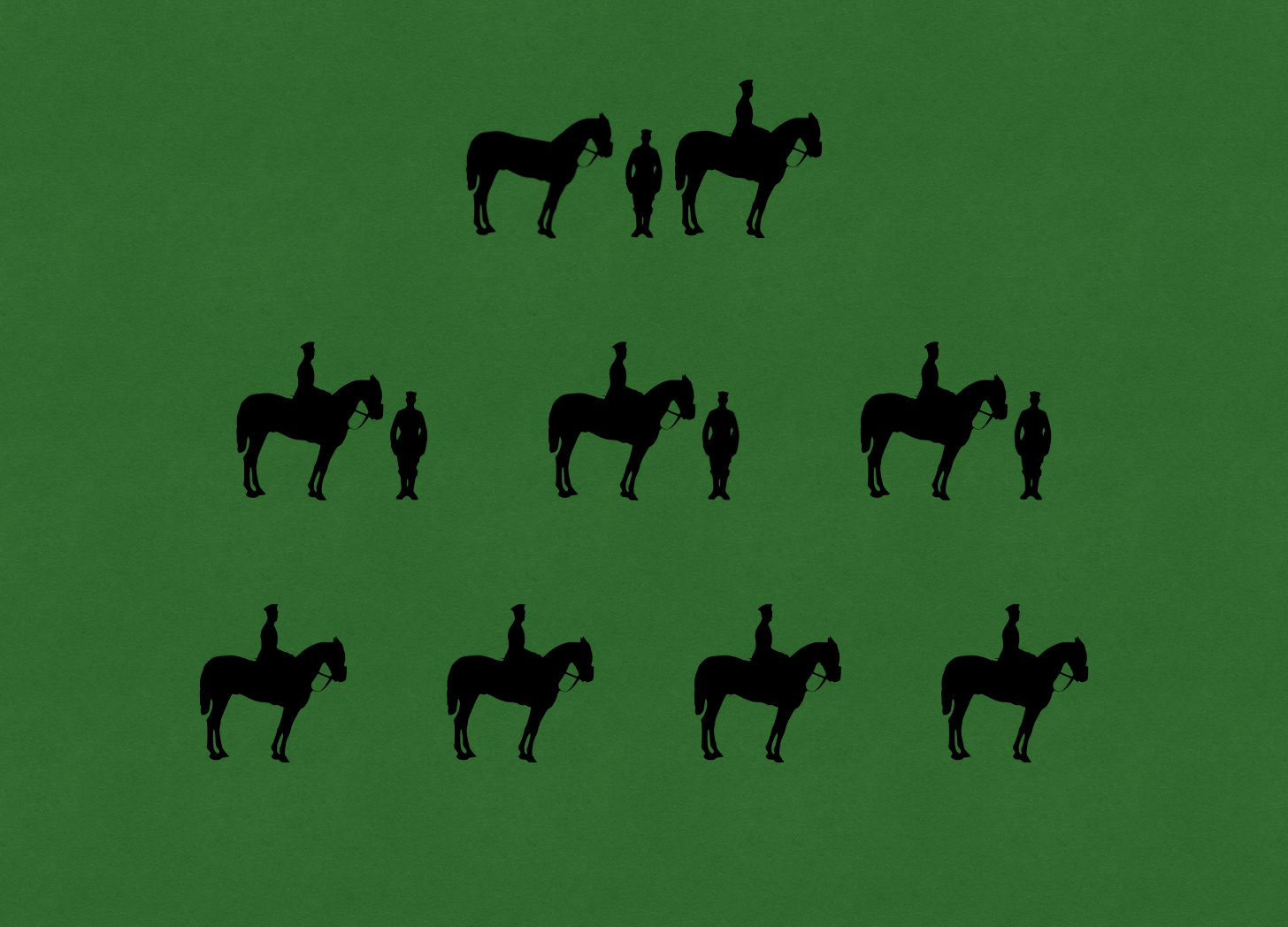

Horses

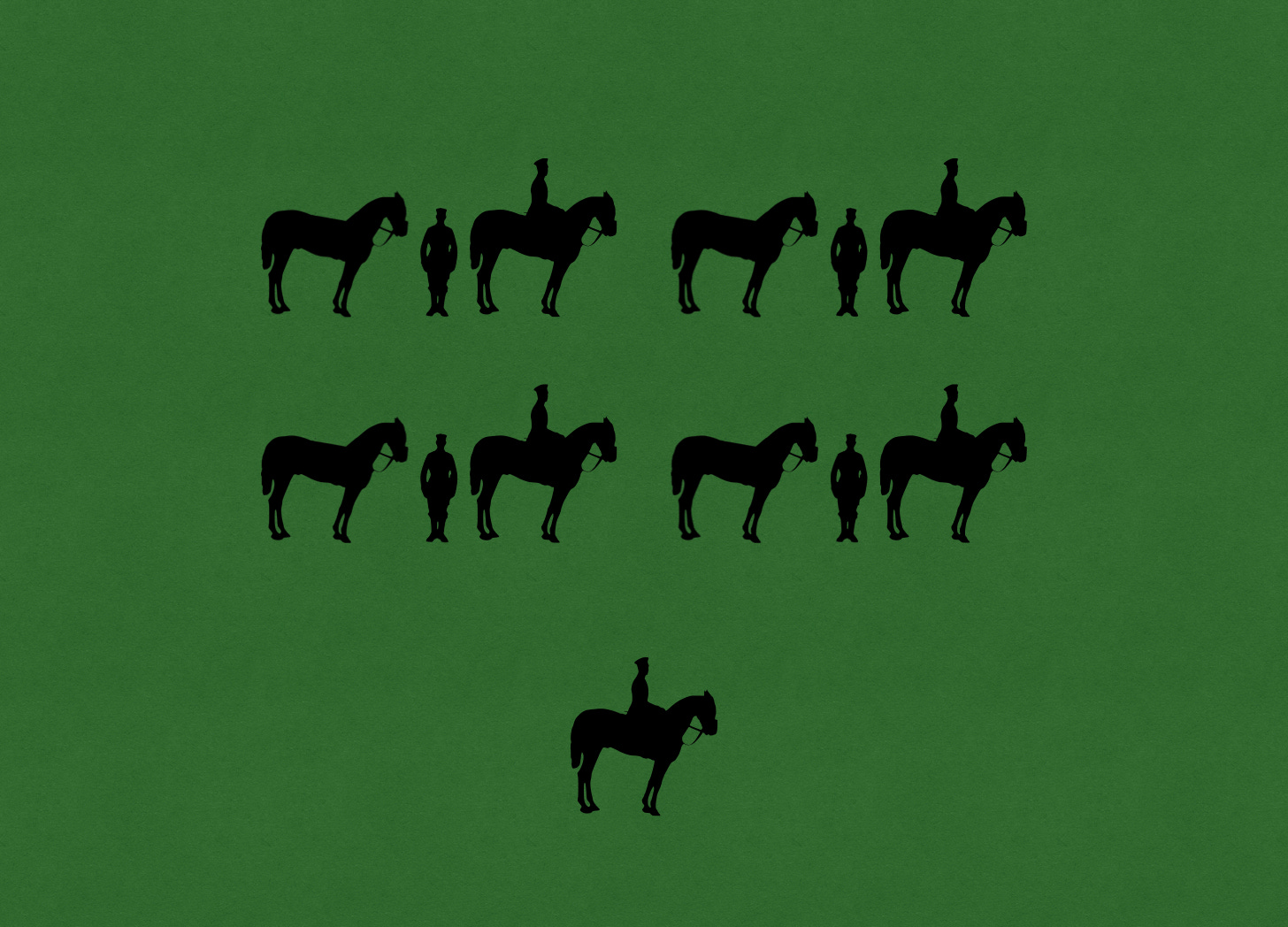

The larger ‘tail-to-tooth’ ratio of the machine gun company owed much to the relatively large number of horses allocated to it. Where the larger unit possessed 32 draft horses and 9 riding horses, the smaller outfit made do with 14 draft horses and 2 riding horses. Likewise, where the company rated 21 soldiers defined by duties related to the leading, feeding, watering, driving, and holding of horses, the platoon received but 8 men who specialized in services of that sort. (Most of these men ranked as privates. One or two, however, could have worn the collar buttons of a Gefreiter.)

Some of the horse handlers of infantry machine gun units, called ‘drivers’ [Fahrer], drove the two-horse wagons that carried machine guns and machine gun ammunition. The rest, known as ‘train soldiers’ [Train-Soldaten] served either as grooms for the chargers ridden by officers or as drivers of the wagons that carried things (such as food, fodder, baggage, or equipment) other than items of ordnance.

Of the thirteen train soldiers of the machine gun company, four served as grooms for the horses of the four officers allowed to each unit of that type. (Each officer, whether the company commander or one of the three platoon commanders, took two horses into the field with him.)

The farrier [Fahnenschmied] of each machine gun company was the only enlisted man within a machine gun company to rate a mount. However, that non-commissioned officer, who ranked as a sergeant [Unteroffizier] and supervised the routine health care of creatures of the equine persuasion, got by with neither a groom nor a second horse.

Instead of nine riding horses and four grooms, each field machine gun platoon got by with two mounts (both of which belonged to the lieutenant who commanded the unit) and a single horse-holder.

Sergeants and Specialists

A machine gun company rated eleven non-commissioned officers. Of these, six received specific mention in the table of organization for that unit and five were listed simply as ‘sergeants’ [Unteroffiziere].

The named non-commissioned officers were the first sergeant [Feldwebel] and the deputy first sergeant [Vize-Feldwebel], the farrier [Fahnenschmied] and the fodder-master [Futtermeister], the armorer [Waffenmeister-Unteroffizier], and the medical sergeant [Sanitäts-Unteroffizier]. Apart from the first sergeant and his deputy, all of these soldiers wore the edged coat collars of an Unteroffizier.

Most of the unspecified sergeants seem to have served as leaders of machine gun crews. One, moreover, may have led the four-man telephone team authorized to each company of an infantry regiment. However, as there were but five sergeants for these seven jobs, one or two of the six machine gun crews in the company would have been led by senior Gefreiten.

A field machine gun platoon was authorized no more than five non-commissioned officers: a deputy first sergeant [Vize-Feldwebel], an armorer, and three unspecified sergeants. The deputy first sergeant also served as the fodder master for his unit. The armorer might have ranked as an ‘armorer sergeant’ [Waffenmeister-Unteroffizier] or an ‘armorer’s assistant’ [Waffenmeister-Gehilfe]. (In the latter instance, I presume that the armorer would have been a Gefreiter.)

Where the armorer of a machine gun company enjoyed the services of three assistants [Waffenmeister-Gehilfen], his counterpart in a field machine gun platoon worked alone. Similarly, where the farrier of a machine gun company could count on the help of a blacksmith [Beschlagschmiede], the blacksmith of a field machine gun platoon was the only practitioner of his trade in the latter unit. Finally, where a machine gun company was authorized a saddle-maker [Sattler], a wheelwright [Stellmacher], and the aforementioned medical sergeant, a field machine gun platoon possessed no organic means of fixing its wagons, repairing items made of leather, or patching up its people.

Refinements

On 28 March 1915, the War Ministry of the Kingdom of Prussia revised the establishments for mobile machine gun units of the contingents subject to its wartime jurisdiction. In doing so, it provided them with the means of establishing telephone networks, redistributed riding horses, and gave a fourteenth wagon to the machine gun company, and made provision for ‘shield bearers’ [Schild-Träger].

The document that promulgated these changes added 8 telephonists [Fernsprecher] to each field machine gun platoon. At the same time, it mentioned that the issue of protective shields [Schützschilden] and telephone equipment to each machine gun company resulted in the assignment of 15 additional men to outfits of that type. Unfortunately, neither the author of the cover letter that explained this change, nor the draftsman who drew the associated table, explained how many of the fifteen new men strung wire and how many carried steel shields.

The redistribution of riding horses deprived all lieutenants of their second chargers. In machine gun companies, the horses made available by this change allowed the mounting of three non-commissioned officers: the first sergeant, the deputy-first sergeant, and the fodder master. In field machine gun platoons, the second horse of the platoon commander became the mount of the deputy first sergeant.

Cooperation and Expansion

The organization of field machine gun platoons suggests that the designers of such units presumed that nearby machine gun companies would provide them with a number of important services. Indeed, in the spring and summer of 1915, a number of infantry regiments went so far as to merge attached field machine gun platoons into their organic machine gun companies.

On 8 July 1915, the Prussian War Ministry published a letter forbidding this practice. Field machine gun platoons, it explained, were complete units that, while attached to particular infantry regiments, remained at the disposal of the Supreme Command [Oberste Heeres-Leitung]. The same letter, however, made provision for the assignment of an additional machine gun crews to units that had managed to obtain additional machine guns. (A machine gun company or field machine gun platoon was allowed one sergeant and eight men for each machine gun, whether German or captured, that it added to its inventory. Moreover, for every two supernumerary machine guns it obtained, it rated a mounted platoon commander and three additional privates.)

Source: Prussian War Ministry, letters of 28 March 1915 and 8 July 1915, preserved in folder PH 3 1238 by the German Federal Archives [Bundesarchiv].

For Further Reading:

To Share, Subscribe, or Support:

In 1984 the Marine Corps returned the M-2 .50 cal machine gun to infantry battalions. Designated “heavy machine gun platoon” which was part of weapons companies.

Designed to be deployed in general support of the battalion or distributed to the line companies.

In general support it could be deployed as a reconnaissance element or as part of anti armor killing teams.

T/E was 8 heavy machine guns with tripods and traversing and elevation mechanisms or mounted on M151 jeeps and later hummers.

Then 8 M-60 machine guns.

This configuration was created during the hight of the cold war and was designed to enhance a infantry battalion’s ability to hold the line against a soviet attack into NATO specifically Norway which was the Corps responsibility.

I was assigned as a platoon commander (as a gunnery sgt) for this unit in 1st Battalion 2nd Marine Regiment which was the Corps designated cold weather regiment. We deployed to Norway during that time and moved our equipment vis akios which is a toboggan pulled by 4 Marines in snow shoes.

Needless to say my Marines where bulls.

I retired in 2007 so most likely that unit may no longer exist in that table of organization and equipment.

"I find myself imagining that someone in Berlin divided the number of available machine guns by the number of available lieutenants. (I cannot say that this actually happened. However, if the archival documents I have perused over the decades are any indication, such adventures in arithmetic appealed greatly to folks who wielded pencils in the war ministries of the age of steel and steam.)"

I wonder if you might share some other cases where such a logic was present, or at least very highly probable. It's the kind of oob/personnel-policy detail I find absolutely fascinating, but it can be so rare to find even in otherwise excellent scholarly works.