The oldest and, at the same time, the most common (by far), of the field pieces employed by the Finnish Army was the 76.2mm (three-inch) field gun adopted by the Imperial Russian Army in 1902. Also known as the Putilov (from the company that built them), these had much in common with the other quick-firing field guns adopted by various European armies in the decade that began in 1897. That is, it could send projectiles weighing seven kilograms or so (roughly fifteen pounds) over relatively flat trajectories to out to ranges that rarely exceeded seven kilometers (four miles.)

The Russian field gun of 1902 enjoyed one clear advantage over most other weapons of its class. Where the shells fired by most other quick-firing field guns began their journeys through the air at speeds that varied from 465 to 510 meters per second, projectiles projected by the Putilov pieces flew much faster, with a muzzle velocity of some 590 meters per second. (The comparable figure for the runner up in this competition, the famous French 75mm field gun of 1897, was 525 meters per second.)1

For the first dozen years of its existence, the 76.2mm field gun of 1902 served chiefly as a means of firing shrapnel shells. As the speed with which such shells traveled provided the cloud of bullets released by such projectiles with the lion’s share of their ability to do damage, the high muzzle velocity of the Putilov piece gave it an edge over its competitors.

During the First World War, shells filled with high explosive, which gained little benefit from speed, displaced shells filled with dozens of little lead balls. Thus, what had been an advantage became a cost. (For one thing, high speed shells traveled over a relatively flat trajectory, thereby complicating attempts to strike enemy soldiers on the far side of hills. For another, the larger propellant charges needed to impart additional impetus to shells added greatly the wear and tear experienced by the interior of the piece each time it fired.)

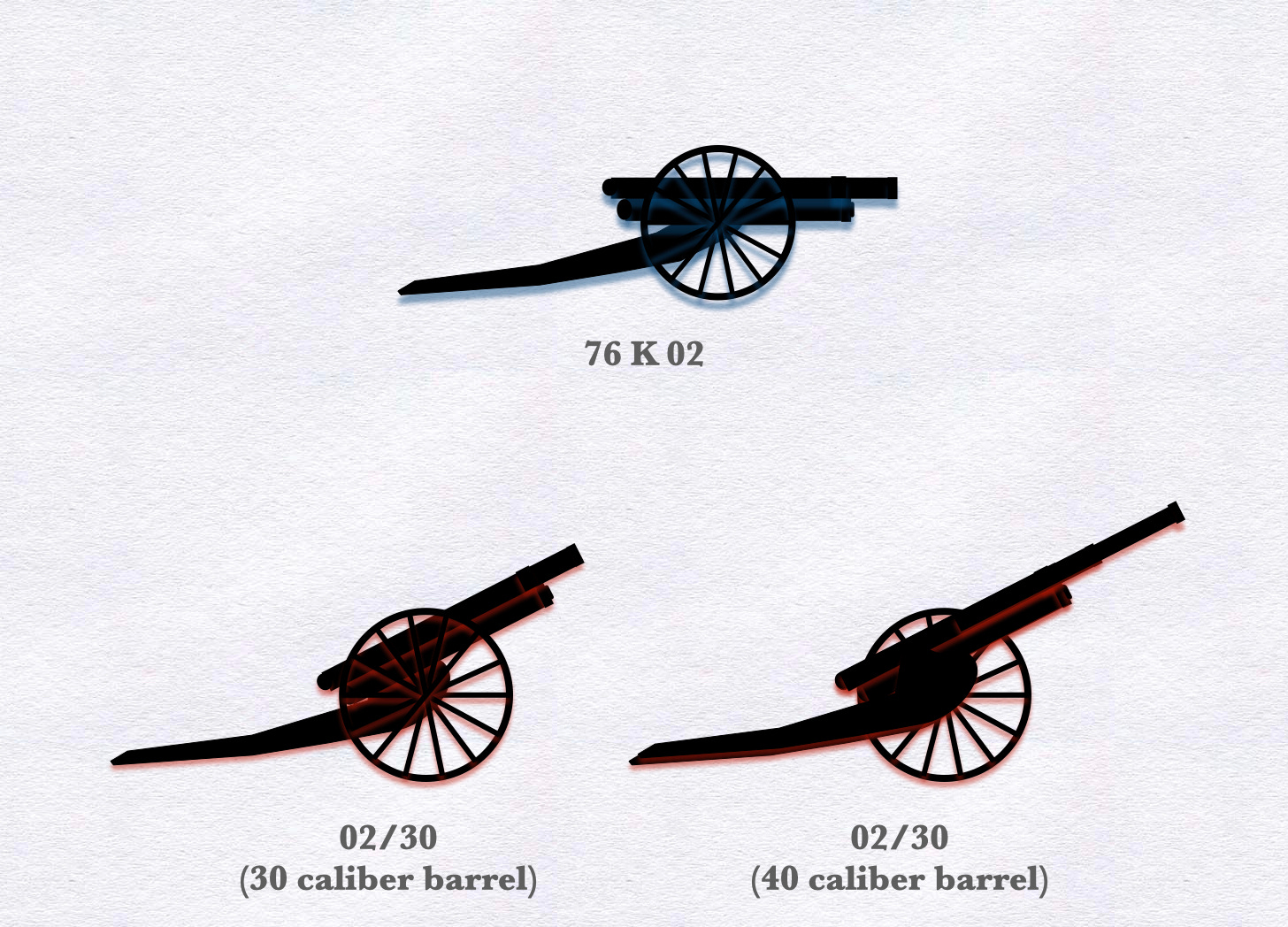

Nonetheless, in the 1920s, when gunners in the service of the new Soviet state went looking for a light field piece for the Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army, they settled upon an updated version of 76.2mm field gun of 1902. To be more specific, they mounted the barrel assembly of the Czarist field piece upon a new carriage, thereby increasing the highest achievable elevation of the barrel from 17 degrees to 37 degrees.

The ability to fire at higher angles allowed the improved field gun, which was adopted in 1930, to reach more distant targets. It also increased the ability of Soviet gunners to drop shells behind hills, ridges, and other bits of high ground that shells fired by the original field piece would not have been able to reach. (As the distance that a given shell could fly depended on both the peculiarities of its design and the specifics of the propellant charge employed, figures for the maximum range of the two versions of the three-inch field gun vary widely. That said, I think that it is safe to say that, all other things being equal, a shell sent skywards by the updated field gun of 1930 could travel two kilometers further than one delivered by its immediate ancestor.)

In the early 1930s, Soviet gun founders placed a 40-caliber barrel upon the carriage of the improved three-inch field gun. (The barrels of the first two guns in the series were but 30 calibers long.)2 The resulting weapon retained some elements (such as the breech mechanism and wheels) of the model of 1902. However, given the much longer barrel and the changes made to the recoil mechanism in order to accommodate it, this second descendant of the Putilov gun of Czarist times might well be described as an entirely new weapon.

For Further Reading:

The muzzle velocities quoted presume the use of a shell that weighed seven or so kilograms. The French 75mm field gun also fired a smaller shell that, due to its weight of five and a half kilograms, began its journey through the air at 584 meters per second. All of the figures quoted in this paragraph come from Hans Linnenkohl Vom Einzelschuss zur Feuerwalze (Bonn: Bernard und Graefe Verlag, 1996) pages 66-74.

When used to describe the length of the barrel of an artillery piece, a caliber is a unit of measure equal to the diameter of the bore. Thus, the 30-caliber barrel of a 3-inch gun is 90 inches (2.28 meters) long.

Were there more improvements before the start of WW2?