Enlistment in the Royal Engineers on the Eve of the First World War

The British Army of 1914

Welcome to the Tactical Notebook, where you will find more than five hundred tales of armies that are, armies that were, and armies that might have been.

In the years leading up to the outbreak of the First World War, an institution known as the “trade test” distinguished the engineer branch of the British Army from that of most other armies. Before being permitted to enlist in the Royal Engineers, a man had to show that he could lay a course of bricks, maintain a steam engine, frame a house, or put an iron tire on a wagon wheel. As these skills were usually obtained in the course of a formal apprenticeship, the trade test meant that enlistment as a sapper was effectively restricted to “tradesmen” – members of the top tier of the British working class of the day.1 As such men tended to have more options in life than the unskilled laborers who provided the bulk of peacetime recruits to other arms, prospective sappers had to be induced to join the Royal Engineers by such things as additional pay and a three-year term of active service.2

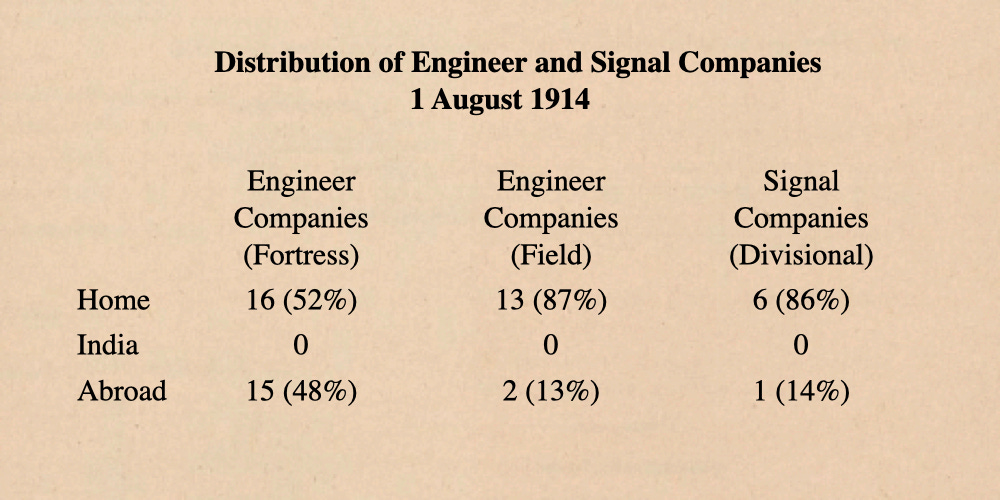

In the view of most British military officers of the pre-war era, a three-year term of active service was an impediment to efficiency. In particular, it complicated the task of maintaining the strength of overseas garrisons by increasing the number of men who could not be sent abroad. (This category of “non-deployable men” was chiefly composed of recruits who had yet to complete their initial training and men who were a few months short of completing their periods of active service.) In the case of the engineer units associated with infantry divisions – field companies and signal companies – this problem was mitigated by the fact that the vast majority of such units were serving at home. (While the field formations of the Indian Army relied upon the British Army to provide a substantial proportion of their infantry and cavalry, as well as all of their field artillery, they were entirely self-sufficient where engineer units were concerned.)

In the case of fortress companies, however, the problem of maintaining the strength of overseas units was exacerbated by the large number of such units serving overseas. Because of this, fortress companies at home suffered from a poor state of readiness. In additional to being chronically understrength, they were burdened by an excessively large number of new recruits and an unhealthy proportion of “time expired” men, sappers who had recently returned from overseas assignments and were awaiting imminent transfer to the Army Reserve.

The three-year term of active service for men of the Royal Engineers was not entirely bereft of advantages. In particular, this peacetime burden created a set of resources that proved very useful upon the outbreak of war. The combination of three-year active service with a nine-year reserve obligation created a pool of reservists that was proportionally larger than the reservoirs created by arms with longer terms of active service. (A three-year term of active service produced twice as many reservists as a six-year term and nearly three times as many as an eight-year term.)

The need to accommodate a constant influx of new recruits forced the Royal Engineers to maintain a disproportionately large training establishment. The relatively short period of time available to train new recruits encouraged the use of systematic training methods, techniques that were much more suitable to large-scale mobilization than the “on-the-job training” techniques favored by organizations that, like the coast defence companies of the Royal Garrison Artillery, were designed around substantially longer terms of active service.

Sources:

Report of the Kitchener Committee on Organization and Training of the Corps of Royal Engineers The National Archives (Kew) WO 32/11378

War Office Statistics of the military effort of the British Empire during the great war, 1914-1920 pages 162, 165, and 166

To Subscribe, Share, or Support:

Men who wished to enlist in the Royal Engineers as drivers, telegraph operators or bandsmen also had to prove their skills in their respective areas. However, because their work lay outside the realm of building things and operating machinery, they were not classified as “sappers.”

All of those who enlisted in the Regular Army incurred a twelve-year service obligation. The number of those years actually spent in uniform, however, varied greatly from one arm to another. Most infantrymen, cavalrymen and gunners served for six, seven or eight years “with the colours” and spent the rest of their twelve-year term of service in the Army Reserve. Sappers served three years as full-time soldiers and nine years as reservists.

That's interesting. Today's army wouldn't get recruits that know how to change a tire, or even the oil.