Depicting Infantry Guns

Tactical Symbols

In the days when field artillery pieces frequently fired over open sights, batteries could assist nearby infantry units by rolling up a gun or two to engage particularly obstreperous obstacles. When, however, gunners adopted the custom of indirect laying, and moved several thousand meters to the rear of the places where foot soldiers fought, the infantry found itself bereft of such support. It is thus not surprising that, as early as the autumn of 1914, the armies fighting in Europe, and the armourers who supplied them, began to look for new ways to provide infantry units with the means of delivering relatively large projectiles at relatively close ranges.

The armies of the German Empire quickly settled upon two solutions to this problem, both of which used relatively light weapons to deliver projectiles of roughly the same caliber as those fired by the standard (7.7 cm) field guns of the day. The first of these was the light (7.58 cm) Minenwerfer (“mine thrower”), which tossed its shells at high angles. The other was the Russian (7.62 cm) “anti-assault gun,” which turned out to be an excellent means of shooting shells over short, relatively flat, trajectories.

In 1917, German formations at the front began to take delivery of a model of light Minenwerfer that could deliver its shells over a wide variety of trajectories. This proved so handy that, soon after the end of the First World War, the army of the new German Republic adopted it as a dual-purpose Infanterie Geschütze (“infantry gun.”) (To be more precise, the German Army of the interwar period provided each infantry regiment with a company armed with six of the new light Minenwerfer and two medium Minenwerfer, which fired shells that weighed in at 50 kilograms.)

To depict these weapons, the companies equipped with them, German draftsmen employed variations on the Minenwerfer symbol used during the First World War.

In the latter half of the 1930s, the rapidly expanding German Army replaced its dual-purpose light Minenwerfer with weapons of two very different types. While it planned to provide each infantry battalion 81mm mortars of the Stokes-Brandt persuasion, it also resolved to provide each regiment with eight direct descendants of the repurposed anti-assault guns of the First World War. Six of these, designated as “light infantry guns,” would fire 7.5 centimeter shells that weighed six or so kilograms apiece. The other two, called “heavy infantry guns,” would fire 38 kilogram shells with a diameter of 15 centimeters.

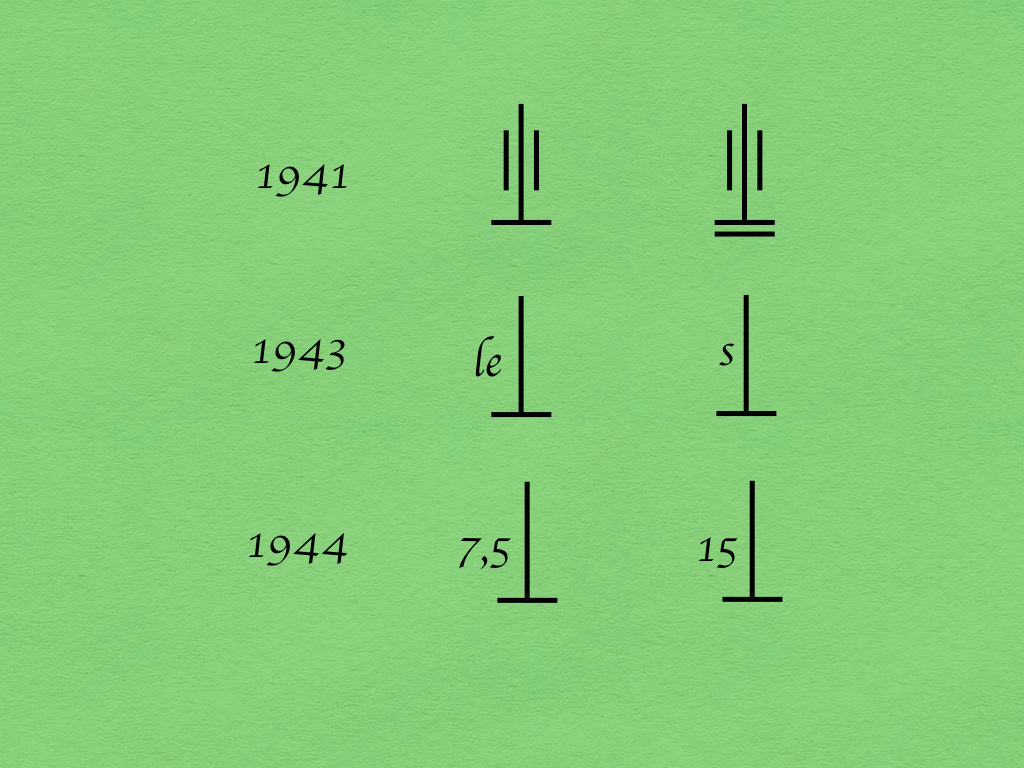

As the Stokes-style drop-fired mortars inherited the hieroglyph previously used to indicate the presence of Minenwerfer, German draftsmen needed new symbols to represent the two types of infantry gun. They created these by the simple expedient of placing the old symbol for light field gun (which also served as the generic symbol for a field piece of any sort) on top of horizontal lines. (One line identified the weapon in question as a light infantry gun. Two lines depicted a heavy infantry gun.)

In 1943, simplified symbols replaced the slightly more complicated hieroglyphs used to depict infantry guns. When, however, the new symbols were drawn on maps, it was often hard to distinguish infantry guns from anti-tank guns. Thus, clever draftsmen adopted the convention of placing the radical representing a gun pit on top of the glyphs for each type of ordnance.

Note:

The symbols showcased in this article were found in various order-of-battle diagrams for German formations. For a systematic explanation of the tactical symbols used by the German Army in World War II, see the guides posted on the website of Leo Niehorster.

For further reading:

To Support, Subscribe, or Share: