Prior to the Boer War, the “brigade divisions” of the Royal Field Artillery were temporary organizations. In 1900, however, the brigade division became a unit in its own right, with a small but permanent staff and component component batteries that were assigned on a long term basis. Over the course of the five years that followed, the cumbrous title of “brigade division” gave way to “brigade,” a program for quartering all three batteries of a brigade in the same location begun, and the practice of sending batteries overseas as individual units was replaced by the rotation of complete brigades. The field artillery brigade was thus becoming “a little regiment,” a social, administrative and disciplinary unit that was beginning to become much more than a mere assemblage of batteries.1

Notwithstanding the growing influence of field artillery brigades (and thus the lieutenant colonels who commanded them), the start of World War I found the commander of a British field artillery battery with substantially more autonomy than his counterparts in other arms. Tradition held that batteries were the unit of account for field artillery, the echelon at which fire was controlled, and level at which the science of gunnery was reconciled with the art of tactics. The introduction of quick-firing field pieces, which extended both the range and the firepower of a battery, had the effect of increasing this autonomy, as well as increasing the complexity of the technical and tactical problems the battery commander was expected to solve.

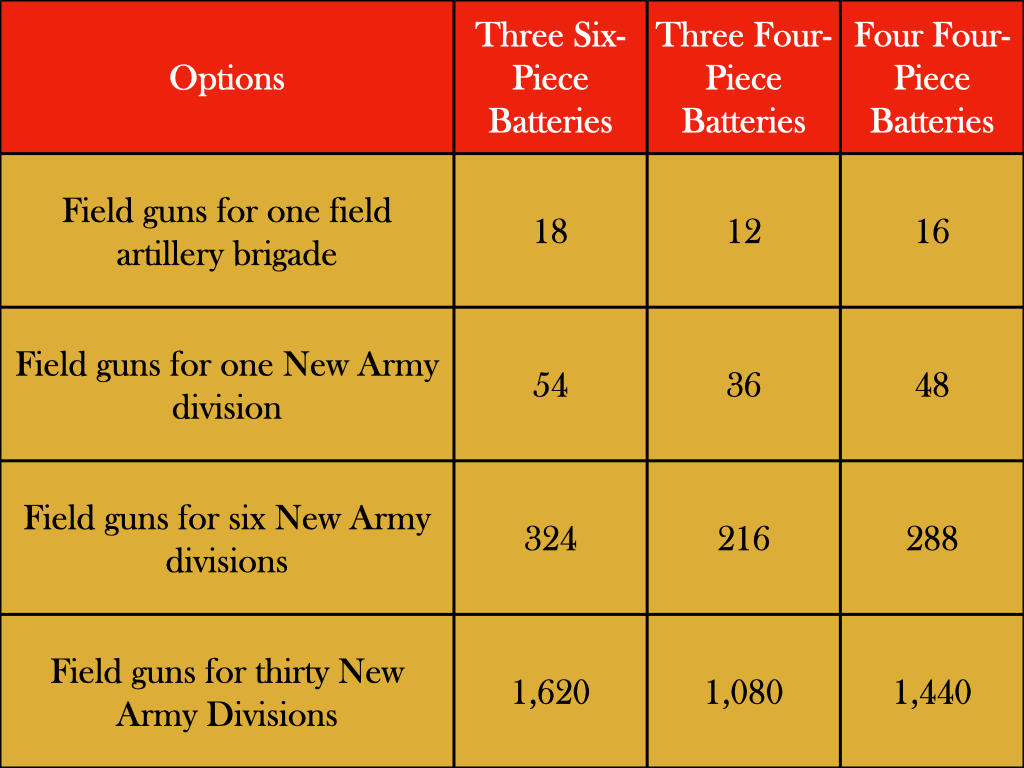

In a mature force of long-service professionals, finding a sufficient number of officers capable of commanding autonomous six-piece batteries had been hard enough. In an army expanding by a factor of five in the course of a single year, providing a qualified commander for each such unit was proving to be an impossible task.

The promotion of every captain who had been serving either as second-in-command of a Regular Army field battery or adjutant of a Regular Army field artillery brigade at the outbreak of the war would have yielded one hundred and eighty majors.2 The appointment of every one of those brand-new majors to the command of one of the three hundred and sixty batteries needed to provide thirty New Army divisions with proper field artillery establishments would have filled half of the anticipated vacancies. To fill the rest, the War Office would have to make battery commanders out of the four hundred or so officers who had been senior lieutenants at the outbreak of the war. To put things bluntly, half of the officers commanding New Army field batteries would necessarily have been much less experienced than the officers who had commanded batteries of the Regular Army in times of peace.

Reducing the number of field pieces in each battery from six to four promised to solve this potential problem by simplifying the work of battery commanders. With four guns or howitzers to control rather than six, a relatively inexperienced officer would have a command that was easier to move, hide, supply, administer, and register on a given target. His battery sergeant major, who would, in all probability, lack the degree of experience normally associated with that rank, would have had a third fewer men to oversee. His similarly unseasoned farrier would have fewer horses in his care, as well as a smaller number of shoeing smiths to supervise.3

In brigades made up of four-piece batteries, the small number of officers who had commanded, or served as seconds-in-command of, six-piece battery before the war would play important roles. The more senior of these experienced officers would take command of brigades, which they would necessarily keep on a tight rein. The less senior, whether commanding batteries of their own or serving as brigade adjutants, would spend a lot of time mentoring the relatively junior captains commanding many, if not most, batteries.

The names given to the field batteries and field artillery brigades of the New Armies reflected the relationship between the two types of organization. Prior to 1914, field batteries of the Regular Army bore numbers that had no necessary connection to the designations of the brigades to which they were assigned. Similarly, most units of the Territorial Force had been named after the communities in which they were located, with batteries named after smaller places and brigades after larger ones. Thus, XL Brigade started the war with the 6th, the 23rd and the 49th Batteries, while the 4th East Lancashire Brigade consisted of the 1st Cumberland Battery (Carlisle) and the 2nd Cumberland Battery (Workington).

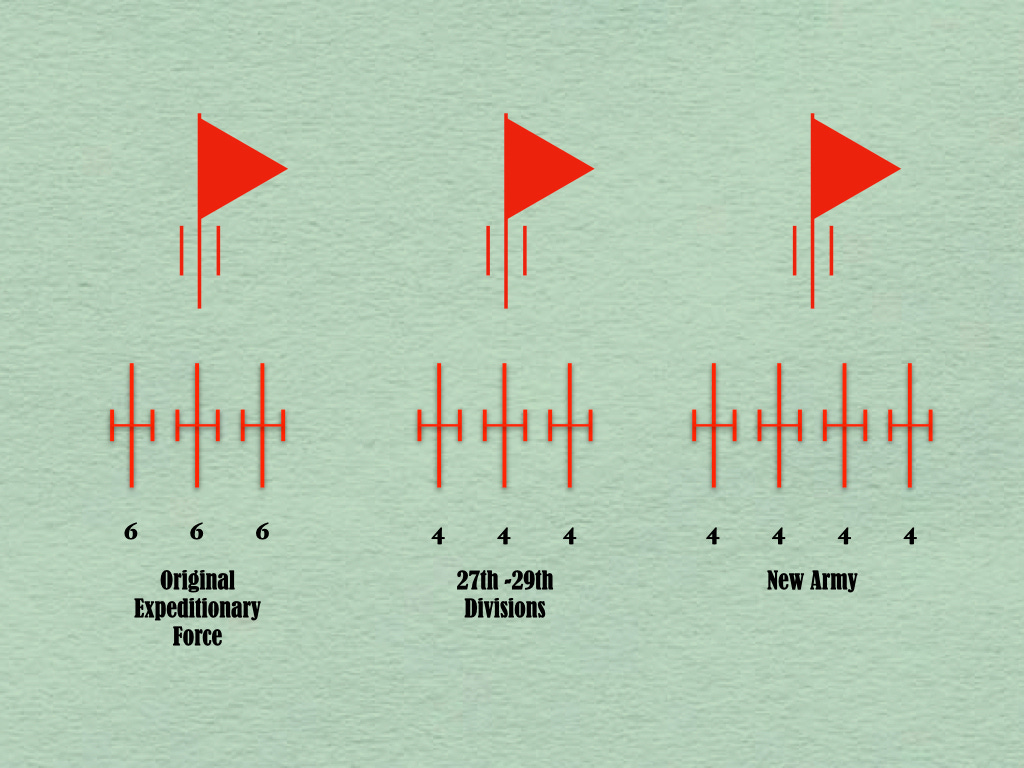

In sharp contrast to these practices, designated of each New Army field battery was created by by combining a letter of the alphabet with the name of the battery’s parent brigade. In other words, New Army field batteries were named in much the same way as the component companies of infantry battalions or the squadrons of cavalry regiments. Thus, for example, when three six-piece batteries of the senior field artillery brigade of First New Army (the 148th, 149th, and 150th Batteries) were recast into four four-piece batteries, the resulting units became known as A, B, C and D Batteries of the XLVI Brigade.4

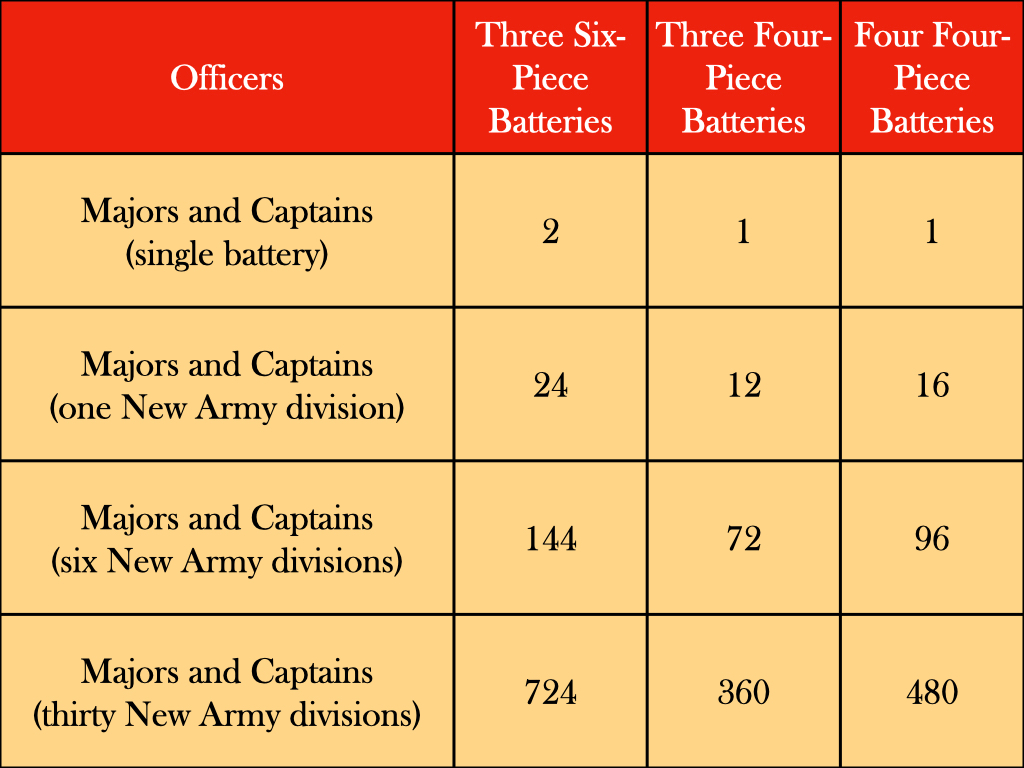

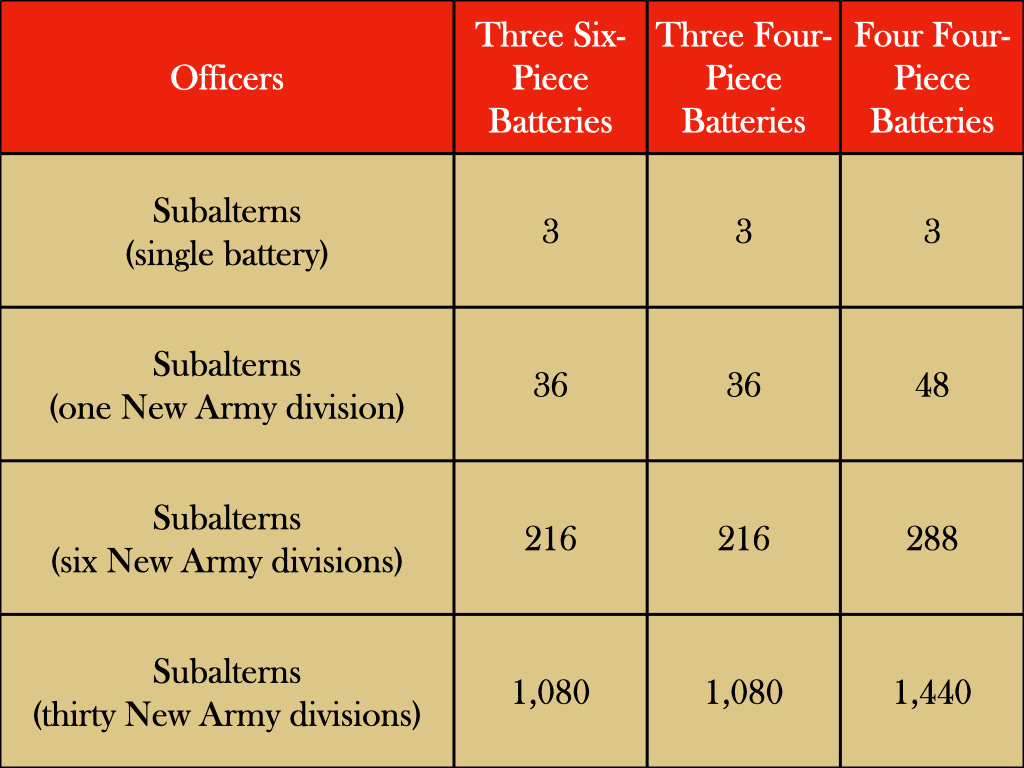

In keeping with the policy of diminishing the degree of independence enjoyed by batteries, the establishments for the New Armies reduced the number of captains and majors serving with those units. Regular Army batteries rated a major (commanding officer), a captain (second-in-command), and three subalterns (one for each section of two guns or howitzers).5 Though four-piece units, Territorial Force batteries were likewise permitted a major, a captain and three subalterns.6 After the imposition of the four-by-four structure, however, the establishments of New Army field batteries authorized the appointment of no more than four officers: a captain or major (as commanding officer), a relatively senior subaltern (as second-in-command) and two junior subalterns (as section commanders).7

The impact of this seemingly minor change in war establishments becomes evident when the number of officers allowed for each type of battery is multiplied by the thirty divisions’ worth of field batteries being formed. The “four-by-four” structure required three hundred and sixty additional subalterns. At the same time, it eliminated the need for two hundred and forty captains and majors. While certainly welcome, this saving of captains and majors was not the decisive argument in favor of the ‘four-by-four’ organization. After all, any structure based upon four-piece batteries would have provided the same benefits. Indeed, if reducing the number of captains and majors had been the only criterion for determining the best organizational scheme, the “expansible battery” (four pieces now, two more later) would have been the preferred option.

The consideration that gave the “four-by-four” structure the decisive advantage over other alternatives was its ability to make full use of the limited number of officers qualified to take up key appointments in the headquarters of field artillery brigades. The placing of a fourth battery in each brigade increased by a full third the number of guns or howitzers that could be managed by a brigade commander and his principal assistant, the senior captain who bore the title of "brigade adjutant." (In contrast to infantry battalions and cavalry regiments, field artillery brigades had no seconds-in-command.)8 At a time when the shortage of experienced artillery officers was painfully obvious and the volume of orders for new artillery pieces was expanding rapidly, such an advantage would have been very tempting indeed. By the same token, it is probably no accident that the most prominent opponent of the ‘four- by-four’ structure was Sir Stanley Von Donop, who was, at this time, openly pessimistic about the ability of British arms manufacturers to produce, in a timely fashion, all of the artillery pieces needed by the New Armies.9

The ‘four-by-four’ organizational scheme was officially imposed on the field artillery establishments of New Army divisions by a War Office letter dated 6 January 1915.10 The decision to adopt this structure seems, however, to have been made several weeks earlier. The first set of war establishments published for the 27th and 28th Divisions, which were issued (respectively) on 7 December 1914 and 16 December 1914, called for the provision to each division of three field gun brigades of the “four-by-four” variety. (The implementation of this plan was prevented by the decision to assign twenty-four field pieces originally set aside for the 27th and 28th Divisions to the newly-formed 29th Division.)11

During that same period, the military authorities in Ottawa ordered the Canadian Division to modify its structure in ways that increased its similarity to its British Army counterparts. Where infantry was concerned, this involved the replacement of the old eight-company battalion with the new four-company battalion.12 For the field artillery, the chief reform was the replacement of brigades organized in the style of the pre-war Regular Army (with three six-piece batteries) with ‘four-by-four’ brigades of the type adopted by for the New Army divisions.13

This article belongs to a series, the other installments of which can be found by means of the following links.

British Infantry Divisions (1914-1918) (I)

British Infantry Divisions (1914-1918) (II)

British Infantry Divisions (1914-1918) (III)

British Infantry Divisions (1914-1918) (IV)

British Infantry Divisions (1914-1918) (V)

British Infantry Divisions (1914-1918) (VI)

British Infantry Divisions (1914-1918) (VII)

H.C. Williams-Wynn, “The Brigade System in the Royal Field Artillery,” Journal of the Royal Artillery, April 1905, pages 17-18

War Office, War Establishments, Part I, Expeditionary Force, 1914, (London: HMSO, 1913), page 83

On the acute shortage of shoeing smiths, see the bound collections of War Office Instructions, TNA, WO 293/1 and WO 293/2.

Becke, Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 3A, page 40

War Office, War Establishments, Part I, Expeditionary Force, 1914, (London: HMSO, 1913), page 83

War Office, Territorial Force, War Establishments (Provisional) for 1908-1909, page 38

War Office, War Establishments (New Armies) for 1915, (London: HMSO, 1915), page 28

The absence of full-time seconds-in-command from the establishments of field artillery brigades seems to have been an artifact of the days when the brigade was little more than a loose confederation of otherwise independent batteries. As might be imagined, this made the job of brigade adjutant a particularly demanding one.

Writing after the war, Von Donop ascribed the decision to adopt the ‘four-by-four’ structure to the Army Council. As he was a member of the Army Council at this time, it is unclear whether he became convinced of the virtues of the “four-by-four” system or was outvoted by the other members. For Von Donop’s autobiographical writings on this subject, see the papers of Sir Stanley Von Donop, which are divided between the Imperial War Museum (IWM 69/74/1) and the British National Archives at Kew (TNA, WO 79/79 through WO 79/84).

Becke, Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 3A, page i

Establishments of the 28th Division (19 December 1914), TNA, WO 24/900.

Minutes for the Meetings of the Military Members of the Army Council, entry for 10 December 1914, TNA, WO 163/45.

Four Canadian war diaries, all of which are on file at the Canadian National Archives (RG9, III-D-3), record this restructuring: 1st Canadian Field Artillery Brigade (Volume 4964, Reel T-10784), 2nd Canadian Field Artillery Brigade (Volume 4964, Reel T-10784), 3rd Canadian Field Artillery Brigade (Volume 4910, Reel T- 10702), and 1st Canadian Divisional Artillery (Volume 4958, Reel T-10775)