At the very start of World War I, the British Army mobilized infantry divisions of two basic types. The six infantry divisions of the Regular Army were formed upon one framework. The fourteen infantry divisions of the Territorial Force were laid out on another.1

Designed by the same people at the same time, these two structures had much in common. Indeed, the chief difference between them lay in the armament and organization of the divisional field artillery. The infantry divisions of the original Expeditionary Force were provided with an ample number of thoroughly modern artillery pieces. A shortage of these first-class weapons, however, forced the Territorial Force infantry divisions to make do with a substantially smaller number of obsolescent guns and obsolete howitzers.2

In the course of the twelve months that followed, shortages of one or more of the indispensable ingredients of field artillery units would continue to plague the British Army. Thus, while the authorities who assembled the many infantry divisions sent out to reinforce the Expeditionary Force were invariably able to provide them with close copies of the infantry, cavalry, engineer and logistics establishments that had been designed before the war, they could not do the same for their field artillery establishments. The result was a degree of organizational chaos that would not be fully remedied until January 1917.

Composed exclusively of infantry divisions of the Regular Army, the original Expeditionary Force had only one way of organizing the field artillery of its infantry divisions. By the end of 1914, the number of distinct infantry division field artillery establishments employed by British Empire forces on the Western Front had grown to four. (Two of these establishments were for divisions composed mostly of units of the peacetime Regular Army that had not been assigned to the original ExpeditionaryForce. The fourth was for the two infantry divisions of the Indian Corps.) Six months later, the presence of a Canadian division, six Territorial Force divisions, and eight New Army divisions increased to seven the number of different organizational patterns for the divisional field artillery of the Expeditionary Force.3

The range of these structures was such that one infantry division might have twice as many field pieces (seventy-two rather than thirty-six) as another. It was also possible for one division to be entirely equipped with the most up-to-date field pieces available to any army on the Western Front while a neighboring formation had to make do with inferior substitutes – weapons that were deficient in range, rate of fire or weight of shell. As a result, the already overworked staff officers, artillery officers, gunners, drivers and horse teams of the Expeditionary Force were subjected to the additional strain of shifting batteries from one part of the front to another. (On 10 March 1915, for example, twenty-one of the forty-six field batteries taking part in the attack upon Neuve Chapelle had been borrowed from divisions that were not otherwise participating in the attack.)4

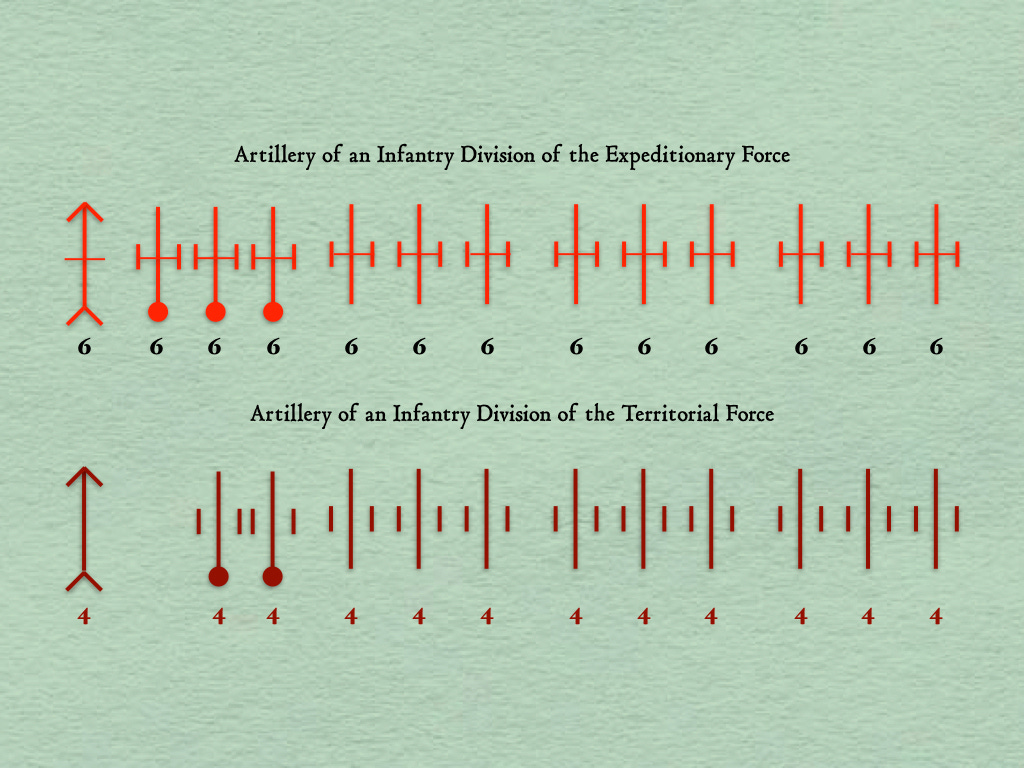

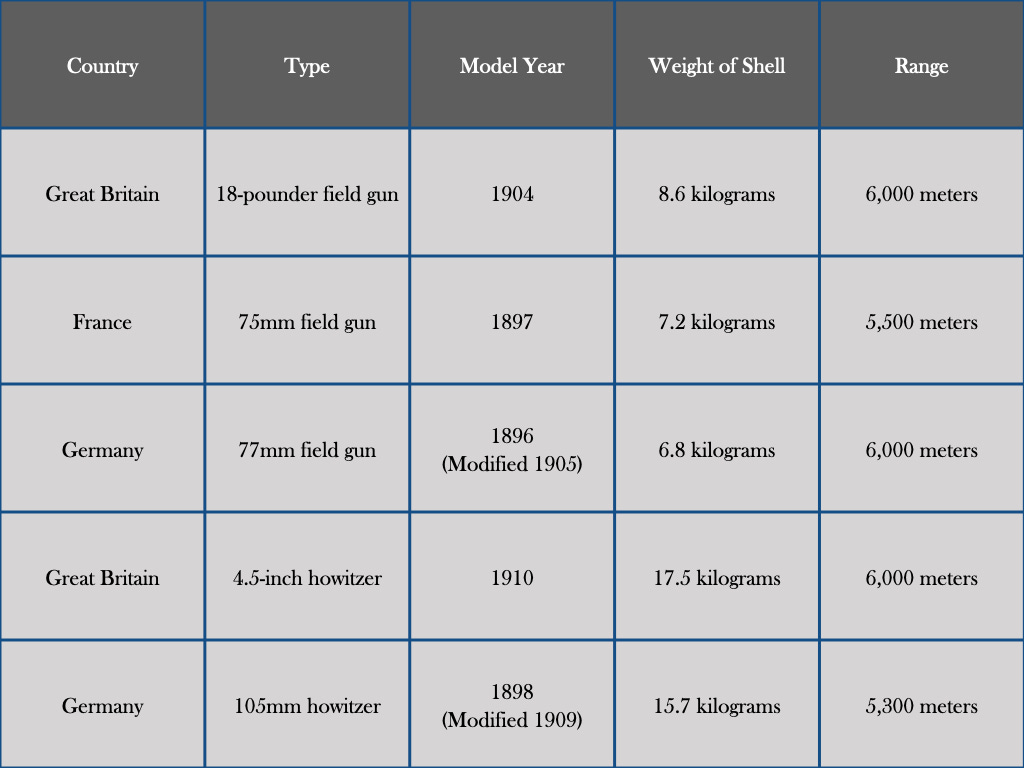

Ironically, the Expeditionary Force began the war with a field artillery component that was strong in numbers, uniformly organized and extraordinarily well equipped.5 Each of the six infantry divisions of the original Expeditionary Force was provided with fifty-four 18-pounder (84mm) field guns and eighteen 4.5-inch (114mm) howitzers.6 A comparable German infantry division (one of the fifty-two most favored divisions of the mobilized German Army) had the same number of field guns and howitzers as an infantry division of the original Expeditionary Force. These weapons, however, were somewhat older and much less powerful than their British counterparts.7

A contemporary French infantry division was in an even worse position. Its famous 75mm field gun enjoyed a rate of aimed fire that was superior to that of an 18-pounder, but fired a shell that was substantially lighter. A French division, moreover, had no howitzers at all.8

The field artillery establishments of the six infantry divisions of the original Expeditionary Force were organized into four groups known as “brigades.” Three of these brigades were armed, at a rate of eighteen guns each, with 18-pounder field guns. The fourth was armed with eighteen 4.5-inch howitzers. Apart from the difference in armament, the four field artillery brigades of a division of the original Expeditionary Force were nearly identical. Each was commanded by a lieutenant colonel and consisted of a small headquarters, an ammunition column and three six-piece batteries.

The chief organizational difference between the two types of field artillery brigade stemmed from the fact that each field gun brigade was formally affiliated with a particular infantry brigade. This meant that, whenever possible, each field gun brigade would be located in close proximity to its affiliated infantry brigade. It also meant that, under normal circumstances, the ammunition column of a field gun brigade would only supply small arms ammunition to battalions belonging to that brigade.9

Howitzer brigades, however, were free of any formal connection to particular infantry brigades. Their ammunition columns, which were exclusively concerned with the carriage and issue of howitzer ammunition, were therefore somewhat smaller than those of field gun brigades.

This article belongs to a series, the other installments of which can be found by means of the following links.

British Infantry Divisions (1914-1918) (I)

British Infantry Divisions (1914-1918) (II)

British Infantry Divisions (1914-1918) (III)

British Infantry Divisions (1914-1918) (IV)

British Infantry Divisions (1914-1918) (V)

British Infantry Divisions (1914-1918) (VI)

British Infantry Divisions (1914-1918) (VII)

The organization of the Highland Division differed slightly from the structure of the other thirteen infantry divisions of the Territorial Force. Where the other divisions possessed nine batteries of field guns, the Highland Division had six batteries of field guns and three batteries of mountain guns. Archibald F. Becke, Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 2A (Newport, Gwent: Ray Westlake, 1989), pages 104-5.

Upon mobilization, the Regular Army and Territorial Force divisions also differed where the allocation of mounted troops were concerned. These differences, however, were eliminated in October 1914. Becke, Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 2A, page 150.

The New Armies were created on 6 August 1914 when Parliament authorized the recruitment of 500,000 volunteers for the Regular Army, to serve “for a period of three years or until the war is concluded.” They would eventually provide 30 infantry divisions to the land forces of the British Empire. For organizational details, see Archibald F. Becke, Order of Battle of Divisions, Parts 3A and 3B, (Newport, Gwent: Ray Westlake, 1989).

Untitled Notes, Papers of A.F. Becke, Box 1, Royal Artillery Institution

Before 5 August 1914, the term “Expeditionary Force” was applied exclusively to the field army of six infantry divisions and one large cavalry division that had been created to conduct major campaigns in places other than the British Isles. Once this original contingent began to receive substantial reinforcements, the term “Expeditionary Force” was increasingly applied to all British forces serving on the Western Front. (As late as the middle of August 1914, however, military members of the Army Council were referring to what would become the First New Army as “the New Expeditionary Force.”) Later, when the arrival of other expeditionary forces (e.g. the Canadian Expeditionary Force) led to confusion, the term “British Expeditionary Force” came into general use.

Each of the infantry divisions of the original Expeditionary Force were also provided with a battery of four 60-pounder (127mm) heavy guns. While able to deliver large shells to distant destinations, the 60-pounder was so heavy that, even when provided with large teams of especially powerful horses, batteries armed with that weapon were frequently unable to keep up with other elements of their parent divisions.

The defects of German field artillery equipment were, to a large extent, the function of poor timing. Having rearmed their field artillery batteries just prior to the start of the quick-firing revolution, the German authorities decided to retrofit those pieces with on-carriage recoil mechanisms. As a result, the standard German field pieces of 1914 were inferior to weapons that had been designed, from the ground up, as quick firing weapons. Herbert Jäger, German Artillery of World War I, (Marlborough: Crowood Press, 2001), pages 14-18.

Hans Linnenkohl, Vom Einzelschuß zur Feuerwalze, (Koblenz: Bernard & Graefe Verlag, 1990), pages 66, 74, 76, 86, 89, and 91. Range figures for the shrapnel shell gun are from J. Schott, “Die gegenwärtige Ausrüstung der Feldartillerie mit Kanonen,” Militär-Wochenblatt, 1905, pages 3,326-3,332.

John Headlam, The History of the Royal Artillery, From the Indian Mutiny to the Great War, Volume II (1899-1914), (Woolwich: Royal Artillery Institution, 1937), pages 168 and 213