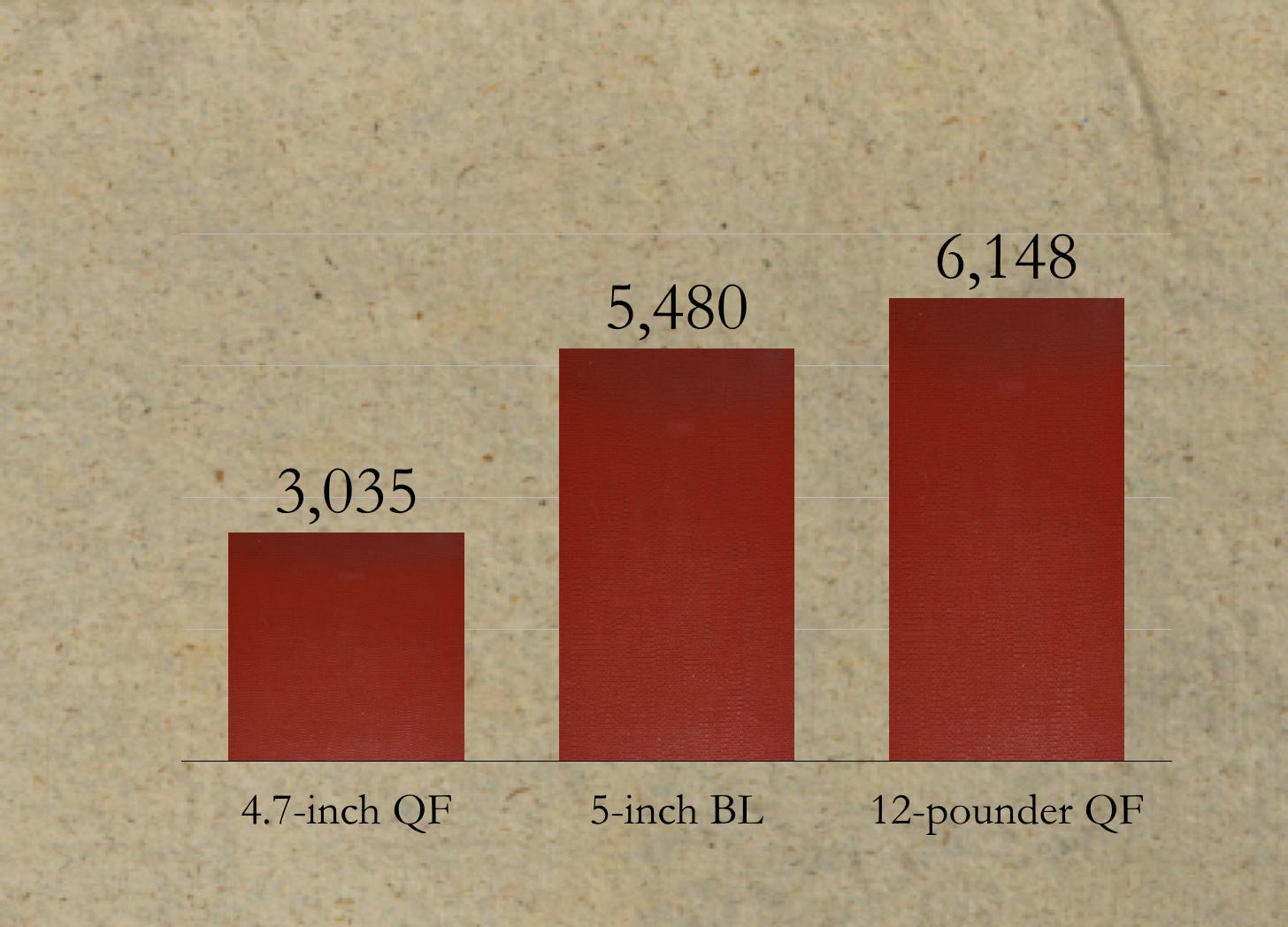

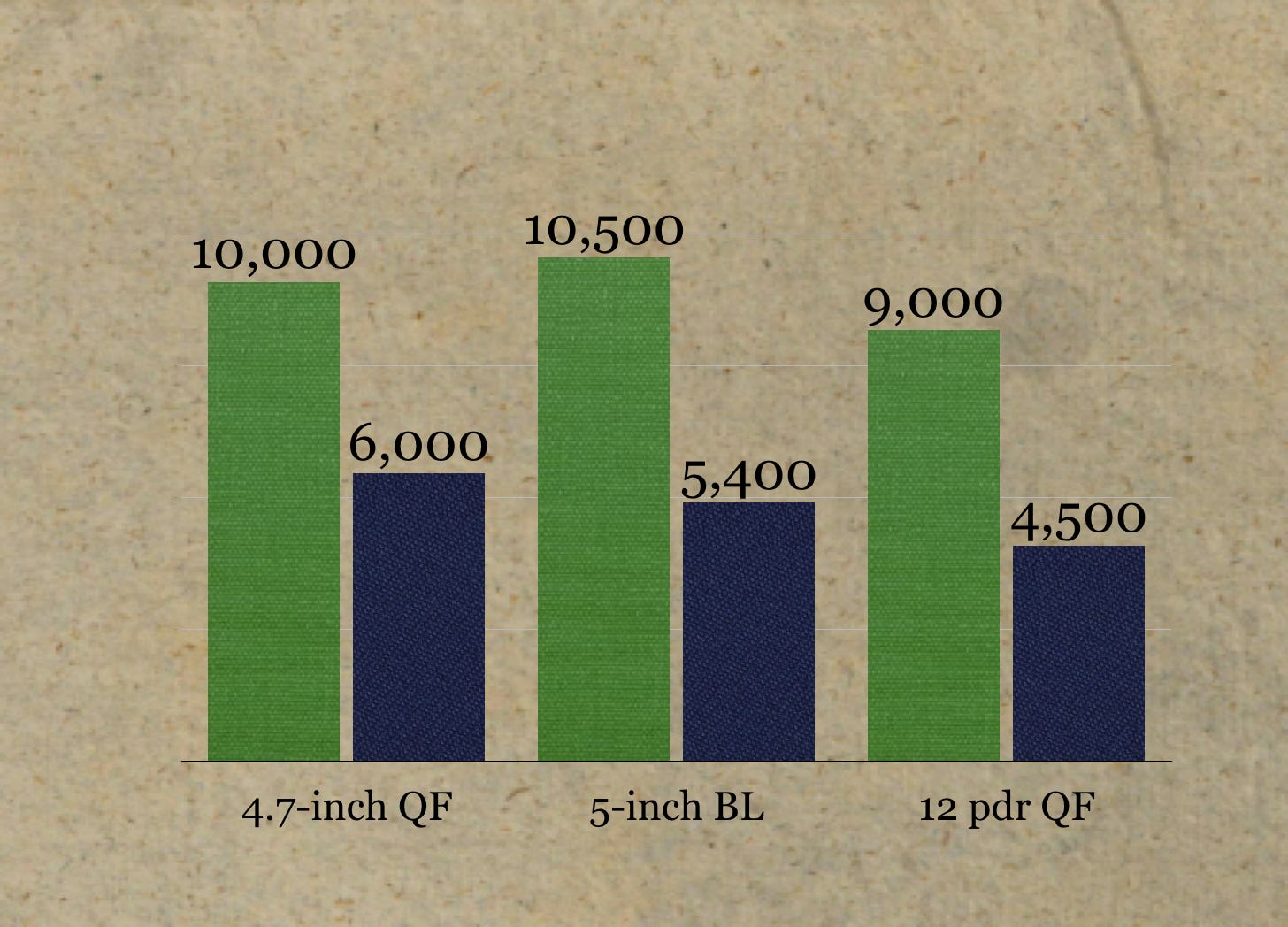

In the course of the Second Anglo-Boer War, 5-inch guns in the service of the British Empire, fired 1.8 rounds for every shell dispatched by 4.7-inch pieces of the long-barreled persuasion. In the same conflict, the ‘long twelves’ exceeded this ratio by a respectable margin, expending a little more than twice as much ammunition as the celebrated ‘four point seven’.1

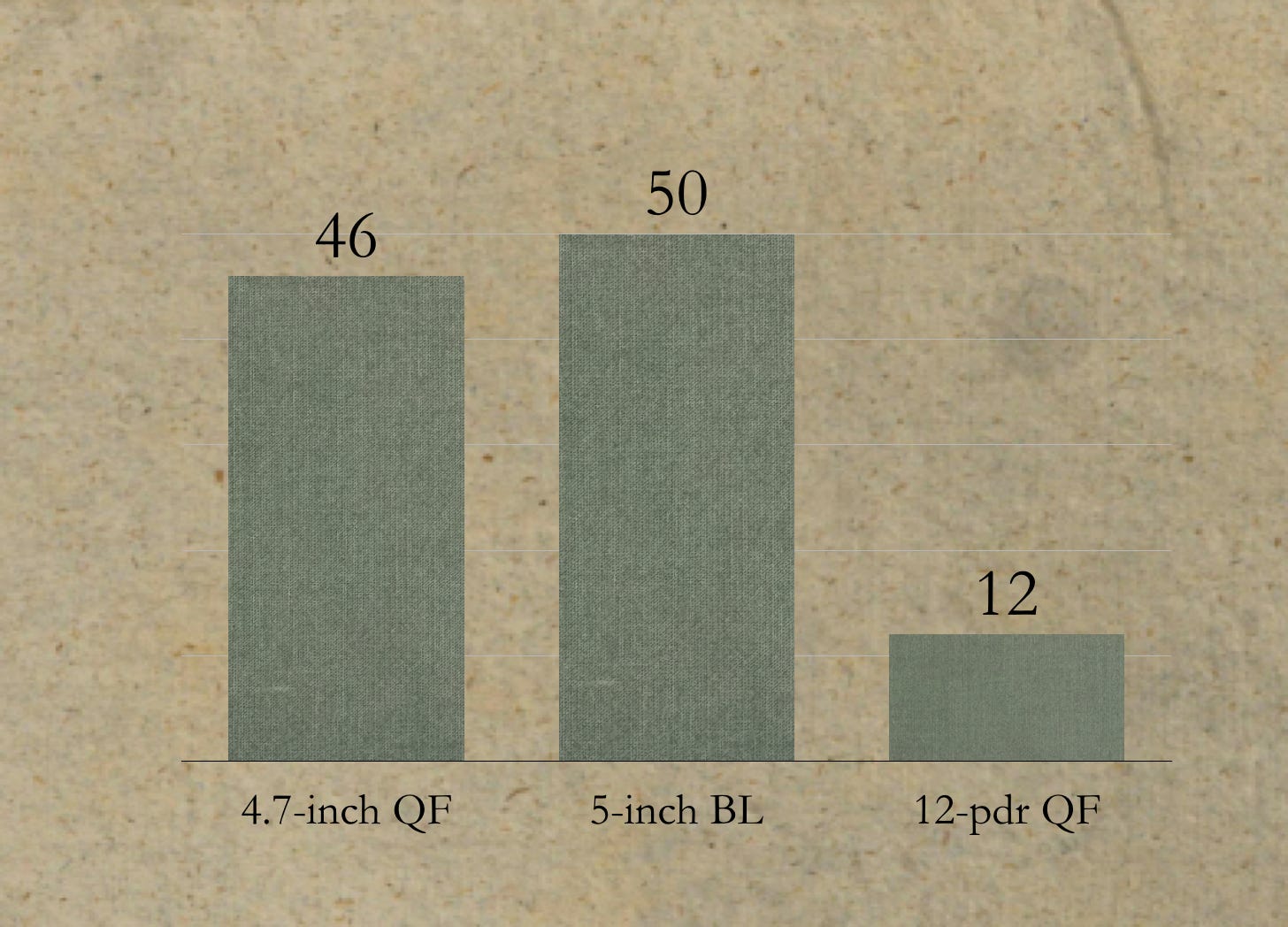

In terms of range, the two larger pieces enjoyed an advantage over the 12-pounder, especially when it came to shrapnel shells. At the same time, they differed little from each other in this respect. (I suspect, moreover, that the range of the 5-inch shrapnel could have been improved by the fitting of a more modern fuze.)2

The shells fired by 4.7-inch guns weighed a little less than those fired by 5-inch guns, but nearly four times as much as those sent into the air by long 12-pounders. (While the weight of the common shell fired by the long 12-pounder reflected its nomenclature, the shrapnel shell of the repurposed shipboard gun weighed 14 pounds.)

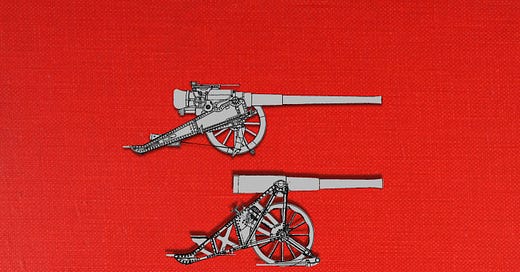

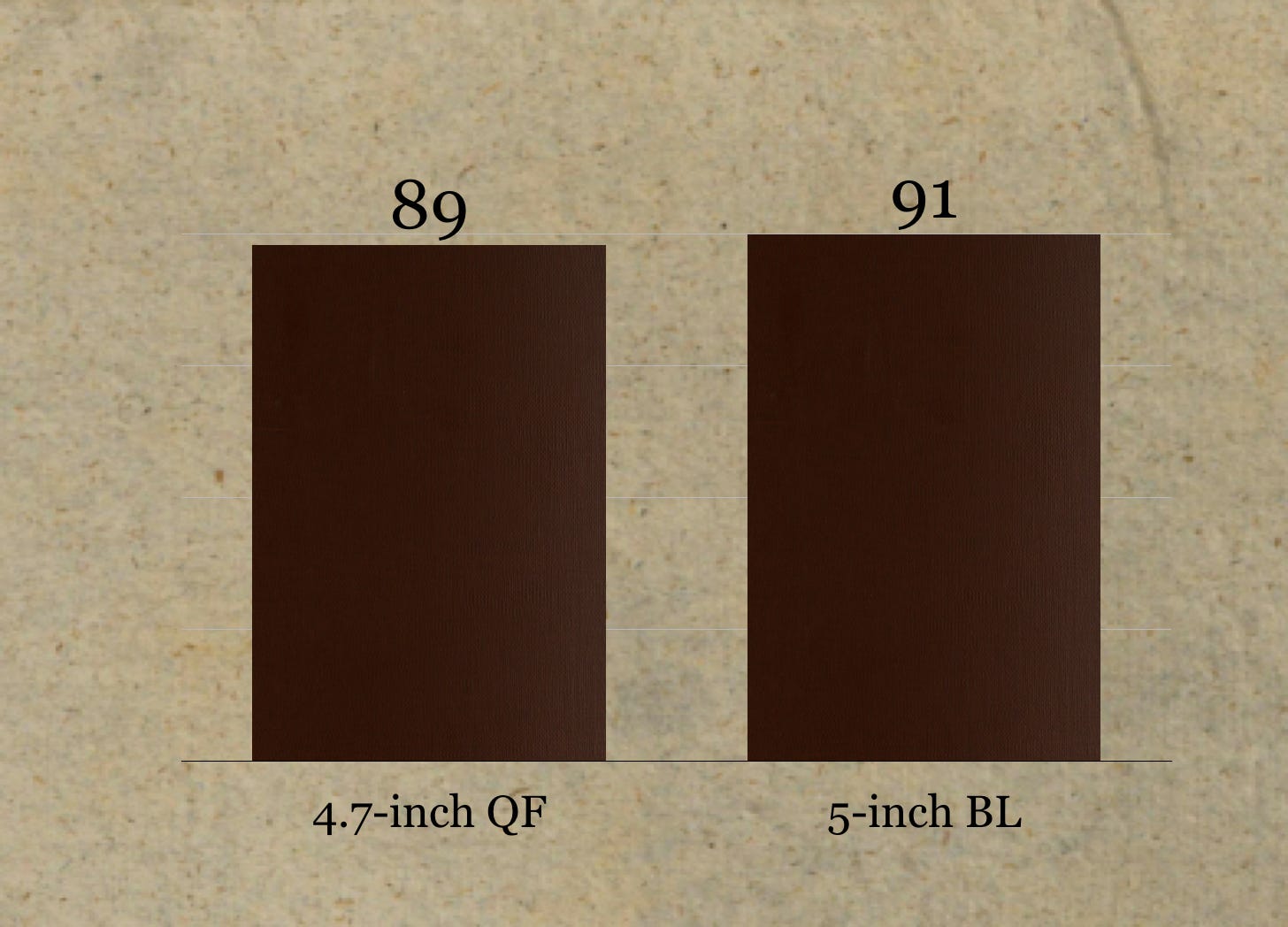

When configured for movement, the 4.7-inch guns placed on the same carriage that carried 5-inch guns placed similar burdens on the beasts that pulled them. (The carriage in question was one that had been designed for an older piece, the 40-pounder rifled muzzle loader.)3

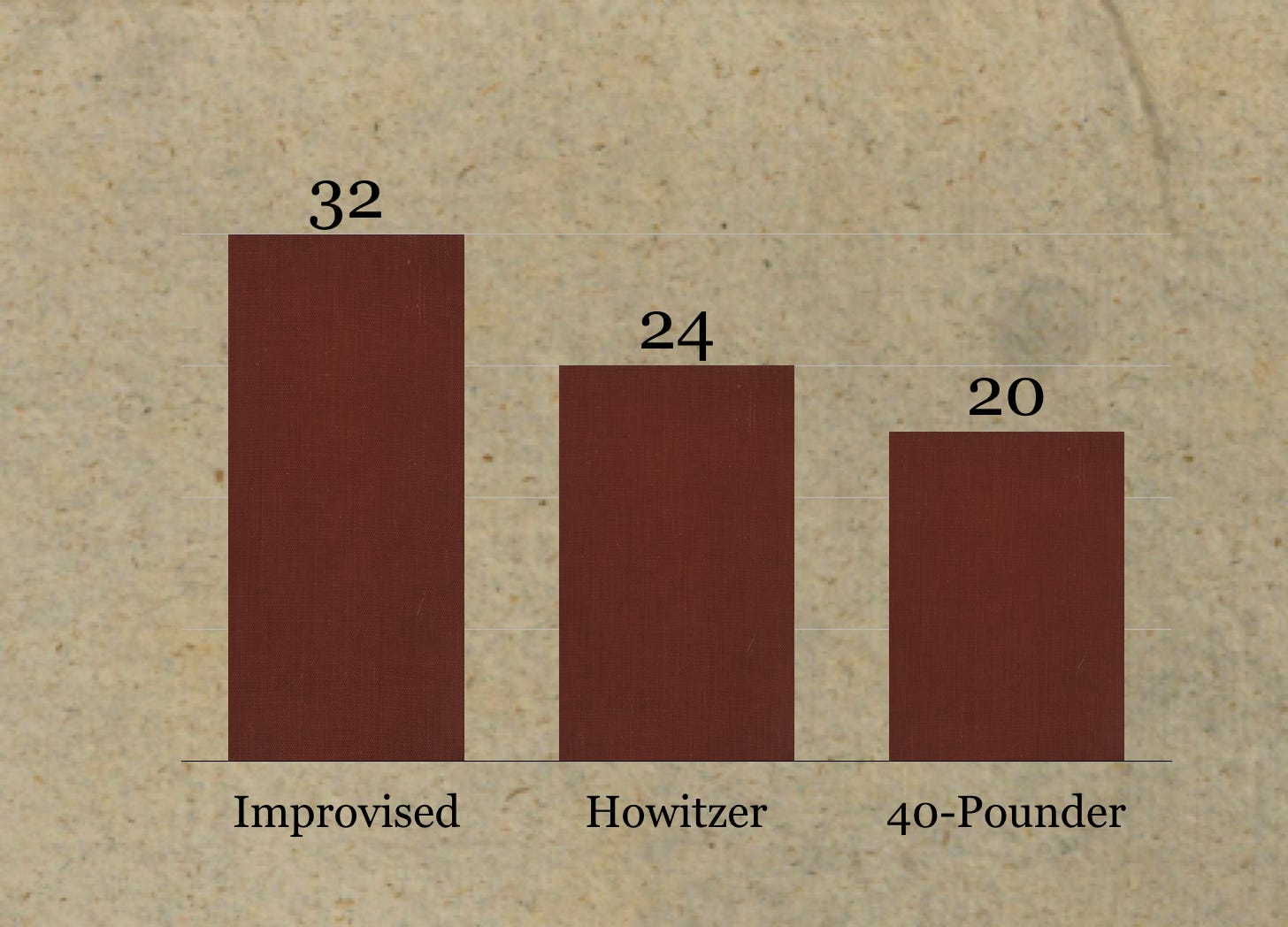

However, while all of the 5-inch guns serving with British forces in the field in South Africa rode atop the carriages inherited from a much older piece (the 40-pounder rifled muzzle loader), some of the 4.7-inch guns were obliged to make do with heavier mountings, whether the traveling carriages of 6-inch howitzers or the mountings improvised local workshops.4

Abbreviations

BL (‘breech-loading’) indicates that the piece uses separate-loading ammunition. That is, the loaders load a bag filled with propellant after loading the shell.

CWT stands for ‘hundredweight’. (Think, if you will, of Roman numerals, or the Latin word ‘centum’.) However, while an American hundredweight equals a hundred pounds, a British hundredweight of 1900 or so weighed in at one hundred and twelve pounds.

Short for ‘quick-firing’, QF tells us that the weapon in question uses fixed ammunition. That is, the propellant is housed in a brass container that might well be described as a scaled-up version of the cartridge case of a rifle round.

Please note the difference between this definition of ‘quick-firing’ and the use of that term to describe the presence of advanced on-carriage recoil-absorbing mechanisms.

For other articles in this series, please see …

To share, subscribe to, or support this newsletter, please visit …

The British Empire forces operating ashore in South Africa used three very different guns with ‘12-pounder’ in their names: the 12-pounder field gun (12-pounder BL), the 12-pounder landing gun (12-pounder 8 cwt QF), and the 12-pounder shipboard gun on an improvised carriage (12-pounder 12 cwt QF).

Filled with an explosive of some sort, a common shell usually bore a percussion fuze. As a result, it exploded when it hit something solid, and thus, barring an encounter with an especially muscular goose, at the far end of its flight. A shrapnel shell, however, usually a carried a time fuze, which did its definitive duty when a powder train within it finished burning, setting off a small charge that opened the projectile, thereby releasing a hail of lead balls.

Unfortunately, I have not been able to find a comparable figure for the weight of the ‘long twelve’.

John Headlam The History of the Royal Artillery from the Indian Mutiny to the Great War, Volume III, Campaigns (Woolwich: The Royal Artillery Institution, 1940 ) page 509

Thanks, never knew what QF meant before.