Though the autumn of 1914 saw a three-fold increase in the size of the Expeditionary Force, no significant changes to the structure of British army corps took place during this period. There was, for example, no development to compare to the creation of corps heavy artillery establishments within French army corps at this time. (The siege batteries and non-divisional heavy batteries sent out to join the Expeditionary Force in September, October, and November 1914 remained under the direct control of General Headquarters.)

The few changes that did take place within army corps were of three types. Within infantry divisions, the number of engineer field companies was increased from two to three. Within some, but not all, infantry brigades, the temporary assignment of a spare infantry battalion (often of the Territorial Force) brought the number of infantry battalions up to five. Among the units assigned directly to the headquarters of each corps, fortress and siege companies of the Royal Engineers displaced squadrons of Irish Horse and infantry companies detached from their parent battalions.

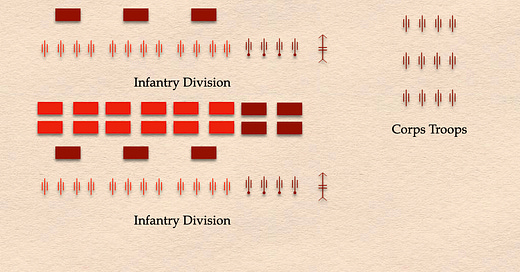

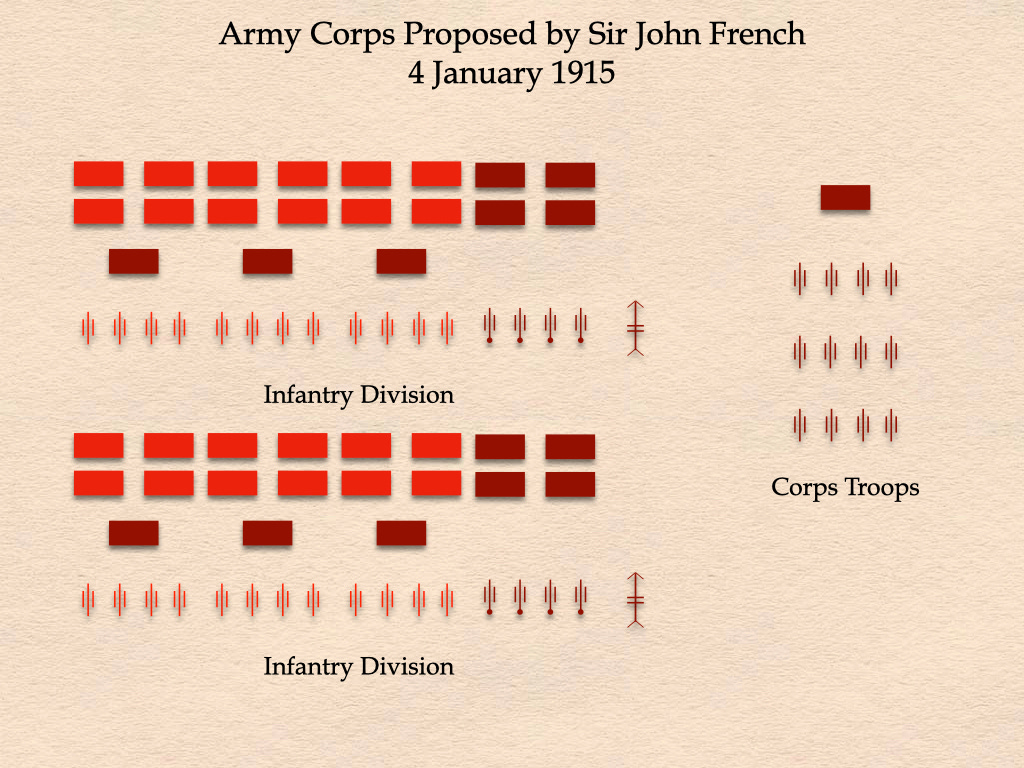

This period of structural stability, however, would soon prove itself to have been the proverbial “calm before the storm.” At the very start of 1915, Sir John French sent a remarkable memorandum to both the Army Council and the Cabinet. In this memorandum, which he called Expansion of the British Army in the Field, he proposed both a moratorium on the creation of new army corps on the Western Front and the dissolution of the six infantry divisions of the First New Army. Units made available by the latter act would then be used to bring the artillery of the six improvised divisions up to pre-war standards, to create a powerful corps artillery establishment for each of the six existing army corps and to increase the number of infantry battalions in each infantry division from twelve to nineteen.

The idea behind this radical reformation of both the division and the army corps was to optimize both formations for the kind of fighting that had taken place in the past few months. “The experience already gained during the war,” French wrote, “has proved that whole units or even formations may have to be temporarily withdrawn from the front to rest and refit…it is therefore desirable that all formations, from brigades upwards, should be reinforced in excess of their normal establishments in order to provide a margin by which their commanders can organize adequate reliefs and so maintain efficiency.”1 To put things another way, French wanted to give each army corps the ability to provide for itself the services that had been provided by elements of the III and IV Corps during the first six weeks or so that each of the latter formations had spent on the Western Front.

Though partially motivated by the losses suffered in mobile warfare in 1914, Expansion of the British Army in the Field was the first attempt by any army fighting on the Western Front to custom-tailor its formations to the peculiar requirements of position warfare. Providing each infantry brigade with an additional battalion would have given brigade commanders the ability to shorten the time that each battalion spent in the trenches. This, in turn, would have reduced the deleterious effect that duty in exposed positions had upon the health of the men. At the same time, periods of rest made more frequent by the presence of a fifth battalion in each brigade would have permitted greater employment of such traditional means of maintaining discipline and morale as uniformity of dress, close-order drill, saluting, and the segregation of men by rank.

The provision of a fifth battalion would also have enhanced the ability of the general officer commanding each brigade to maintain a standing tactical reserve. Likewise, the allocation of a fourth infantry brigade would allow the general officers commanding infantry divisions to a brigade out of the trenches in all situations save emergencies. The existence of such a unit would also increase the likelihood that an infantry brigade that had been engaged in heavy combat could be sent to the rear for rest, refitting and reconstitution.

As radical as it was when it came to the size of units and formations, the expansion scheme of January 1915 did little to alter the relationship between divisions and army corps. The most tangible sign of the tactical self- sufficiency of infantry divisions, the batteries armed with 60-pounder heavy guns, were to be retained by those divisions that had them and provided to those divisions that had been sent overseas without them. Similarly, while described as “corps artillery,” the three additional brigades of 18-pounder field guns allocated to each army corps by Expansion of the British Army in the Field seems to served primarily as a means of relieving brigades in need of rest and reinforcing the brigades permanently assigned to divisions.2

It took the Army Council more than a fortnight to respond to Expansion of the British Army in the Field. While it was pondering the proposal, it received two additional memoranda on the subject of organization. One of these, sent by Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien, simply stated his support for the concept of using any new units that might become available to strengthen existing divisions and army corps. This, in his view, would allow the British Army as a whole to economize on staff officers. The other memorandum, signed by Sir Douglas Haig, described three mutually exclusive courses of action.3

The first of Haig's suggestions proposed the assignment of any additional army corps that might be formed be assigned to one of the two existing armies. Thus, rather than consisting of three army corps, each army would consist of four, five or even six such formations. Haig's second proposal called for the allocation of one New Army division to each of the six existing army corps and the subsequent shuffling of infantry brigades in such a way as to give each division two experienced brigades and one New Army brigade. Haig's third proposal advocated the dissolution of New Army divisions and the parcelling out their component infantry battalions to existing infantry brigades. These six-battalion brigades would then be divided into two “regiments,” each of which consisted of two Regular Army infantry battalions and one New Army battalion.4

As a piece of staff work, Expansion of the British Army in the Field suffered from a fatal flaw: the omission of a substantial portion of the units and formations that stood a good chance of joining the Expeditionary Force in the near future. These included the nine “Imperial Service” Territorial Force divisions still at home, the last of the improvised divisions of the Regular Army (the 29th Division), the Canadian Division, and the twenty-odd Territorial Force battalions that were then being sent across the English Channel as non-divisional units.5 However, when the Army Council finally replied to Expansion of the British Army in the Field, it was tactful enough to refrain from mentioning this obvious mistake. Instead, it sent out a letter that addressed all three of the proposals it had received.

At the heart of the Army Council’s letter was the argument that, while larger formations might be more suitable to position warfare, they were extremely unwieldy when it came time for an army to start moving again. General officers commanding brigades and divisions would have to deal with too many subordinates. Columns of march would be much harder to manage. The billeting and re-supply of formations would become far more complicated. The act of increasing the size of formations, moreover, would render obsolete the administrative and logistics infrastructure that had made such movement possible in August and September. Thus, when the Expeditionary Force resumed the war of movement, it would do so with a set of procedures, war establishments, and service units that had been designed for another sort of war.

In explicitly condemning any permanent increase in the size of infantry brigades or infantry divisions, the Army Council’s reply to Expansion of the British Army in the Field implicitly rejected Haig’s proposal for creation of two three-battalion ‘regiments’ within each infantry brigade. It did not, however, do the same for his proposal concerning the integration of New Army divisions into existing army corps. Indeed, the letter explicitly endorsed both of the definitive features of the latter scheme: the addition of a third division to each army corps and as the rearrangement of infantry brigades within divisions. The Army Council’s reply also endorsed the practice of temporarily attaching supernumerary Territorial Force battalions to infantry brigades.6

In the four months that followed the exchange of letters on the subject of organization, the Expeditionary Force continued to grow. With the singular exception of the Canadian Division, however, the new infantry divisions that joined the British Empire forces on the Western Front all belonged to the Territorial Force. As the infantry brigades of these divisions were often composed of understrength battalions and the field artillery was uniformly armed with obsolete weapons, few argued for a policy of forming them into army corps of their own.7 Thus, as each Territorial Force division arrived on the Continent, it was assigned to an existing army corps. In this way, the two-division army corps of the winter of 1915 became the three-division army corps of the spring of that year.

Expansion of the British Army in the Field, TNA, WO 159/3

Strange to say, Expansion of the British Army in the Field made no mention of the need to affiliate the fourth infantry brigade of each division with a brigade of field guns.

TNA, WO 159/3

TNA, WO 159/3

Becke, Order of Battle of Divisions, Part I, pages 35, 43, 51, 59, 67, 75, 83, 91, 100, and 107; and Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 2A, pages 136-37 and 144-45.

Letter of the Army Council to Sir John French, 20 January 1915, TNA, WO 159/3

For discussions of the problem of understrength Territorial Force battalions, see the correspondence in TNA, WO 293/1 and WO 293/2. For a scheme to amalgamate under-strength Territorial Force battalions, see War Diary, First Army, Administrative Branches of the Staff, entries for 25 May 1915 and 28 June 1915. AC, RG9 (III-D-3), Volume 5068, Reel T-11132.