The decision to refer to a fraction of the Expeditionary Force as an “army” departed from the normal norms of nomenclature in much the same way as the curious contemporary custom of describing groups of two, three or four artillery batteries as ‘brigades.’ Nonetheless, the two component “armies” of the Expeditionary Force were not entirely misnamed. Despite the fact that they were considerably smaller than the field armies that France and Germany planned to mobilize in the event of a European war, they were designed to work in much the same way.

While French and German army corps exercised a multitude of functions, the armies of the Expeditionary Force, like French and German field armies, dealt exclusively with the operational matters. Similarly, while French and German army corps were permanently constituted formations, with subordinate formations as firmly attached as the component units of an infantry division, the armies of the Expeditionary Force, like French and German field armies, had no fixed establishments. Rather, their composition at the start of a campaign was the creature of deployment plans and their make-up in the course of active operations a function of the ever-shifting fortunes of war.

The organizational flexibility inherent in the design of the army headquarters of the Expeditionary Force is well illustrated by three orders of battle drawn up before the war. The first of these was created for the large-scale scripted exercise of September 1913. The second was drawn up as part of a hypothetical scenario used to explain the organization of signal services to engineer officers in 1913. The third was prepared as part of the planning that took place in response to the threat of civil war in Ireland in March 1914.

In the scripted exercise, each army was an identical force of two infantry divisions and one cut-down cavalry division. In the hypothetical scenario, the First Army served as the main striking force of the Expeditionary Force while the Second Army was primarily concerned with guarding an open flank. The First Army, with three infantry divisions, was slightly larger than the Second Army, which had two infantry divisions and a mounted brigade. As the Expeditionary Force in the hypothetical scenario had yet to make contact with the main enemy force, one of its infantry divisions and a second mounted brigade were formed into a general reserve under the direct control of the General Headquarters.1

In the planning for the force to go to Ireland, the War Office made use of an army headquarters to build a miniature field army powerful enough to make an impressive show of force, as well as to relieve any garrison that found itself in difficulty. Consisting at first of a single infantry division and two cavalry brigades, this army (Southern Force) was prepared to absorb one of the two infantry divisions already in Ireland.2

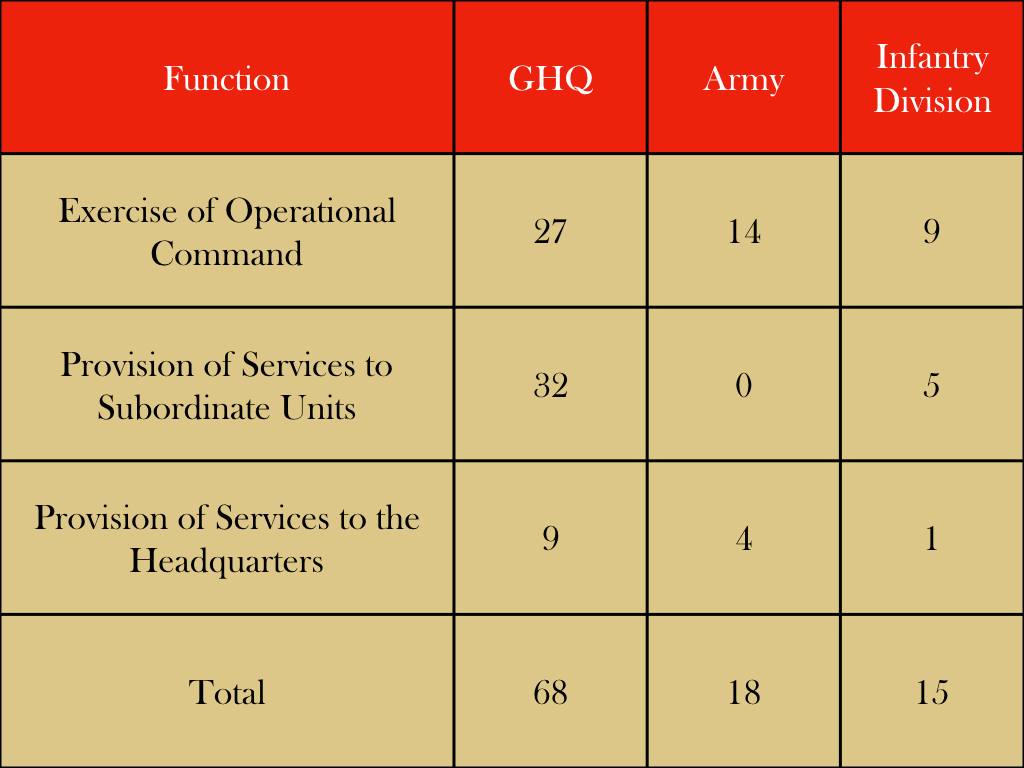

In keeping with the way that “armies” were organized and employed, the two army headquarters of the Expeditionary Force were small organizations that were exclusively devoted to the task of co-ordinating the actions of subordinate formations. That is to say, every one of eighteen officers assigned to an army headquarters was either concerned with the direct exercise of operational command or charged with the provision of services to the headquarters itself.3

Functions of Officers Serving in the Various Headquarters of the Expeditionary Force

1914By way of contrast, a full third of the officers assigned to the headquarters of a contemporary infantry or cavalry division were primarily concerned with the provision of services to subordinate units.4 Similarly, most of non-divisional units normally attached to each army headquarters – the signals units, a squadron of Irish Horse, a company of infantry, and a field ambulance section – supported the headquarters itself rather than its subordinate formations.5

The exception that proves the rule of the exclusively operational focus of army headquarters is provided by the ‘bridging train’, a small column of horse-drawn wagons that carried bridge-building materials too bulky to travel with the engineer companies of infantry divisions. As these materials were usually only sufficient to build a single bridge, the despatch of a bridging train to a division was a discrete event of considerable operational significance. It was, among other things, a signal to the division in question that it was to cross a particular river at a particular place and time. Once the bridge had been built, moreover, the bridging train was obliged to return to base in order to refill its empty wagons. In contrast to this mode of employment, the service units belonging to other echelons, whether the Expeditionary Force as a whole or its component divisions, provided their services on a continuous basis.6

R.S. Curtis, “The Work of Signal Units in War”, The Royal Engineers Journal, November 1913, diagram opposite page 276

G. T. Forestier-Walker, Organisation of the Field Force in Ireland, 22 March 1914, reproduced in Ian F. Beckett, editor, The Army and the Curragh Incident, (London: Army Records Society, 1986), page 94-99

The ‘assistant director of postal services’ of each army headquarters was only concerned with the postal needs of the army headquarters, not the army as a whole. Anonymous, “Manual of Army Postal Services (War)”, The Army Review, October 1913, pages 622-23

War Office, War Establishments, Part I, Expeditionary Force, 1914, pp. 18-29, 45-46, and 48-49

Foster, Organization: How Armies Are Formed for War, pages 79-81 and Edmonds, Military Operations, France and Belgium, 1914, I, pages 456

F.S. Maurice, “Engineers of the Expeditionary Force”, The Army Review, April 1913, page 41 and R.H.H. Boys, “Engineers of the Expeditionary Force”, The Army Review, October 1913, p. 450.