Assault Gun Tactics

A Lauerstellung in Champagne (September 1915)

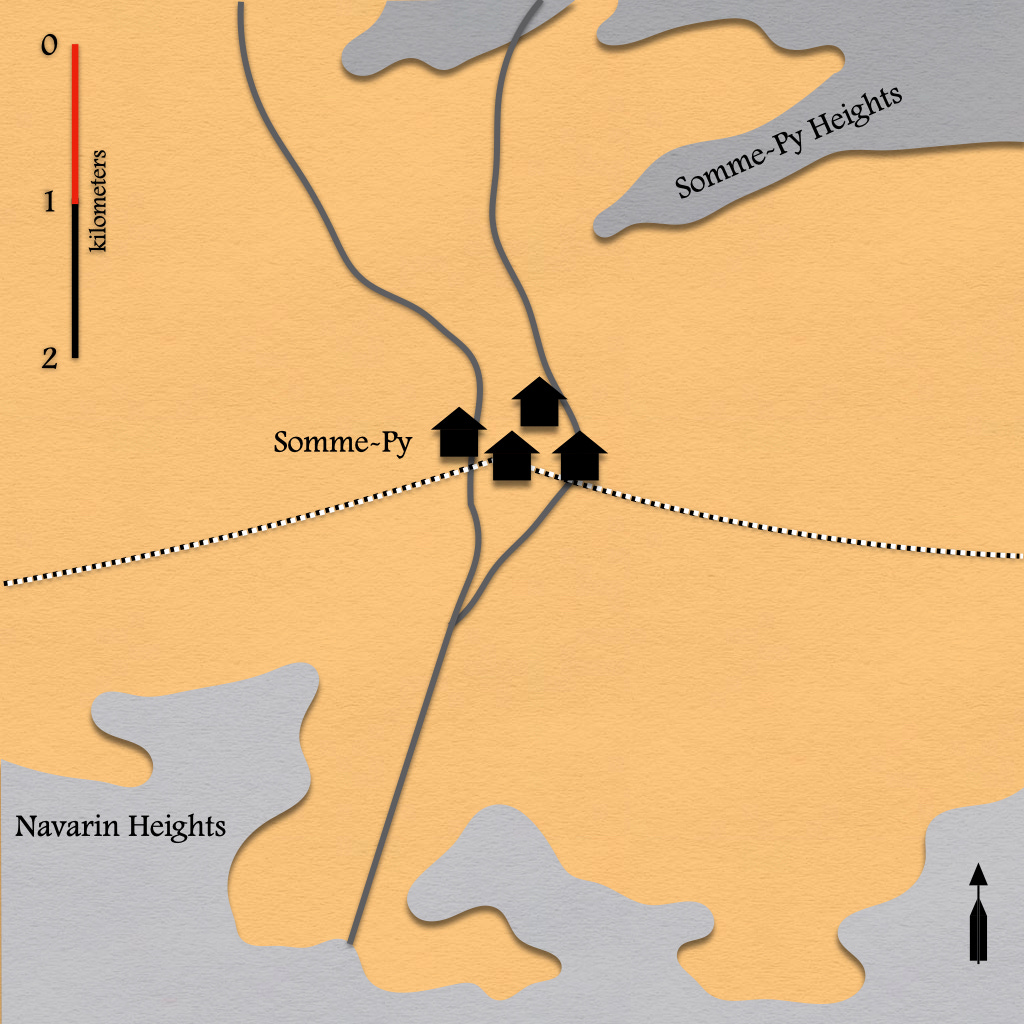

In September of 1915, the 15th Reserve Division occupied two defensive positions on the Navarin Heights. The forward position ran along the forward slope of the ridge, the reserve position along the reverse slope.

Both positions faced towards the south. (Most German positions on the Western Front faced towards the west. However, in the Champagne region, where the Navarin Heights were located, the trenches ran from east to west.)

Six kilometers north of the reserve position, the little town of Somme-Py sat atop the intersection of a railroad and a highway.1 The railroad, which ran from east to west, enabled the German forces in the Champagne to quickly move units from one part of the region to another. The highway, which ran from south to north, provided any French force attacking towards Somme-Py with both a supply route and a means of orientation.

Northeast of the town, another piece of high ground, which the Germans called the Somme-Py Heights, protected a small valley from the fire of French heavy guns. (In the event that the French succeeded in breaking through the reserve position, these heights would form part of a third defensive position.)

On 22 September 1915, at seven in the morning, the French artillery began to fire. Over the course of the three days that followed, close to a million shells exploded over, or upon, the positions held by the 15th Reserve Division, the two divisions on its left, and the five divisions on its right. On the morning of 25 September, at a quarter past nine, the French infantry attacked.

By the evening of the 26 September, the French had captured substantial portions of the German forward position and, in a few places, had reached the reserve position. One of those places was the northern edge of the Navarin Heights.

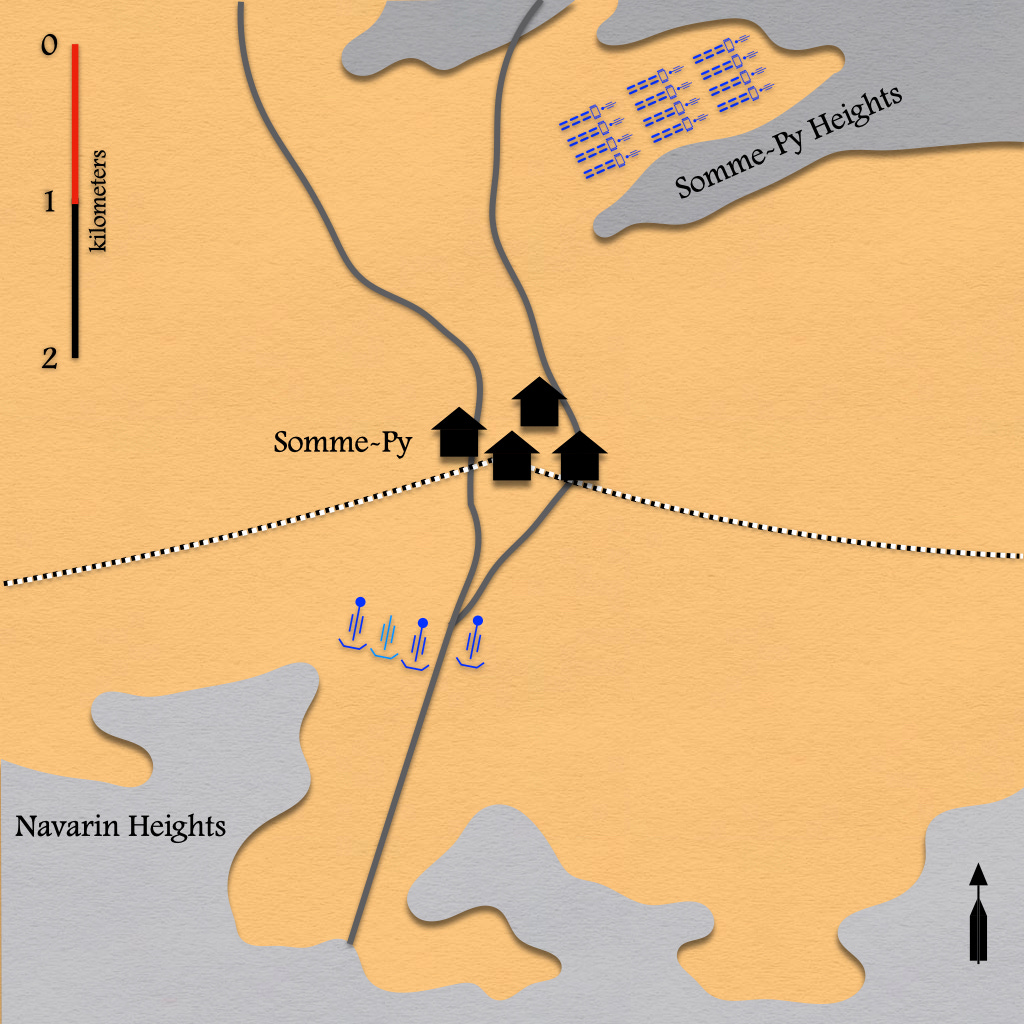

On the morning of 27 September, Major Zimmermann, commanding the 192nd Light Howitzer Battalion of the Royal Saxon Army, reported to Baron von Mühlen, the senior artillery officer of the 15th Reserve Division.2 Mühlen had the option of employing the twelve 105mm howitzers of the battalion to reinforce the fourteen batteries firing in support of the hard-pressed German infantry. Instead, he ordered Major Zimmermann to hide his battalion in a Lauerstellung in the valley north of the Somme-Py Heights.

At that time, the term Lauerstellung (“lair position”) referred to place where a fully-limbered artillery unit awaited the opportunity to take decisive action. In the initial conception of Baron von Mühlen, this would happen when the French infantry broke through the reserve position on Navarin Heights, and began to push north towards Somme-Py.

When, however, this failed to happen, Mühlen made a new plan. The 192nd Light Howitzer Battalion would leave its Lauerstellung, drive south through of Somme-Py, and take up positions a few hundred meters south of the town. There, they would join a field gun battery from another regiment in bombarding the French troops stuck in front of the reserve position.

Sources:

William Balck “Die deutschen Abwehrkämpfe im Westen 1915” in Max Schwarte (editor) Der Große Krieg, 1914-1918 (Leipzig: Barth, 1923)

Kurt Bischoff Im Trommelfeuer, Die Herbstschlacht in der Champagne, 1915 (Leipzig: Gebrüder Fändrich, 1939)

In 1911, census workers found 812 people living in the commune of Somme-Py.

As a rule, field artillery battalions of the German armies belonged to field artillery regiments, each of which consisted of two or three battalions. The 192nd Light Howitzer Battalion, however, was one of a small number of independent field artillery battalions that were raised in the summer of 1915.