Assault Gun Tactics

The Horse Artillery Tradition

In the German Army of the Second World War, responsibility for armored fighting vehicles was divided between two different inspectors. The Inspector of Armored Troops [Panzertruppen] supervised all things related to “tanks” [Panzerkampfwagen], the Inspector of Artillery handled matters connected to “assault guns” [Sturmgeschütze].

This curious division of responsibility provided the assault gun units of the German Army with two benefits. In the realm of technique, it resulted in an emphasis on gunnery, and, in particular, the practice of finding range by bracketing. In the realm of tactics, it led to the use of an approach inspired by the time-honored methods of German horse artillery batteries.

These methods rested upon the notion that, “in a cavalry action every moment is precious, and the time available for the work of the guns passes very rapidly. We must make the most of it and avoid wasting precious moments in long movements. The time for producing an effect being so short we must take care not to lose a moment of it through a lengthy firing to ascertain the range or any want of skill in shooting. The tactics of horse artillery must be simple, the determining of the range rapid, and its skill in shooting of a very high standard of excellence.” 1

In 1915, the Artillery Monthly [Artilleristische Monatshefte] published an article in which the commanding officer of the horse artillery battalion [Reitende Abteilung] of the 7th Cavalry Division described how he put this ideal into practice.

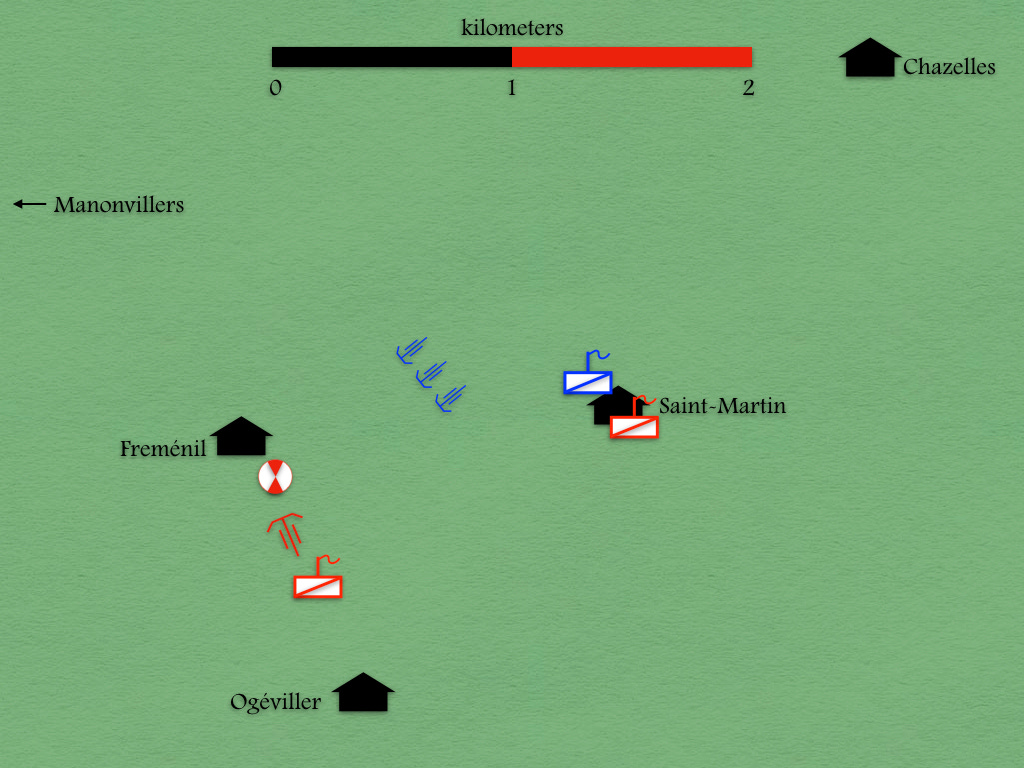

At Chazelles our patrols came rushing back in a headlong gallop calling out: "Strong force of hostile cavalry with cyclists and artillery along the road on the low ground between Frémenil and Ogéviller."

I at once rode over to the Division Commander and requested permission to take up a position southwest of Chazelles on Ridge 297, about 1,500 meters to our front, in order to take under fire as quickly as possible the target, which according to the map, could be done very advantageously.

Before leaving I saw for the first time, plainly visible to our right front, the outline of the Forts at Manonviller, about 8,000 meters distant. My attention was thus called to the fact that it was not impossible that we might come under the fire of the heavy guns located there, a circumstance which became of increasing importance, on account of the French network of telephone communications which was surely in existence and remained undamaged as further events also proved.

After a rapid estimate of the situation and a short discussion with the general staff officer, who believed that the range to the French artillery was not over 6,000 meters with which estimate I, however, disagreed, the advance to the ridge was made at a gallop, the batteries having been ordered to do their utmost to get into position quickly.

In front of us our cavalry was deployed, being previously dismounted to fight on foot, and were firing upon hostile cavalry at St. Martin, who replied with a desultory fire at about 1,500 meters range. Very soon after, our skirmishers withdrew, in order to make room for our batteries which were advancing at a gallop in double section column.

Upon reaching the top of the hill, I saw before me a panorama most alluring for a field artilleryman, a picture such as is seldom seen either in maneuvers or during firing practice. At about 3,800 meters a great highway (Frémenil - Ogéviller) and on it cyclists in columns of twos moving along leisurely; beyond the road some artillery halted in a meadow by the roadside; farther up the slope near the village, a strong force of cavalry in assembling formation.

The neighboring village of St. Martin was occupied by hostile skirmishers, who now were delivering a livelier fire as my battalion headquarters showed itself and our cavalry skirmishers began to withdraw. In sizing up the situation, I had immediately decided to move rapidly into an open position in order not to lose a single second.

Riding along at a gallop, I roughly designated the positions of the batteries, two batteries to the right and one battery to the left of a sheep-pen, batteries to go in the order of march, move by the flank and execute action to the flank. As the battery commanders, not very far distant from their batteries, came up to me, the hostile small-arms fire became stronger but caused no losses.

After galloping for 1000 meters and straining all efforts to the utmost the batteries came through a high field of corn up to Hill 297. Having first oriented every one, I quickly gave only the following orders: "Haste is urgent. Here's a chance to get a few Iron Crosses. Fire upon everything that is standing or moving down there. Right battery, Cyclists; Centre battery, Artillery; Left battery, Cavalry." 2

Adolf von Schell, (A.E. Turner, translator) The Tactics of Field Artillery (London: Harrison and Son, 1889) page 121

A. Seeger (Edmund L. Gruber, translator) “Our Baptism of Fire” The Field Artillery Journal, (October-December 1915) pages 659-665