This is the seventh post in a multi-part series. To find previous installments and those that follow, please consult the following guide.

At first I did not know where I was when I heard these words. There seemed to be a mist in front of my eyes. Gradually it cleared away, and before my friend ceased speaking, to my astonishment, I found myself on a battlefield entirely new to me.

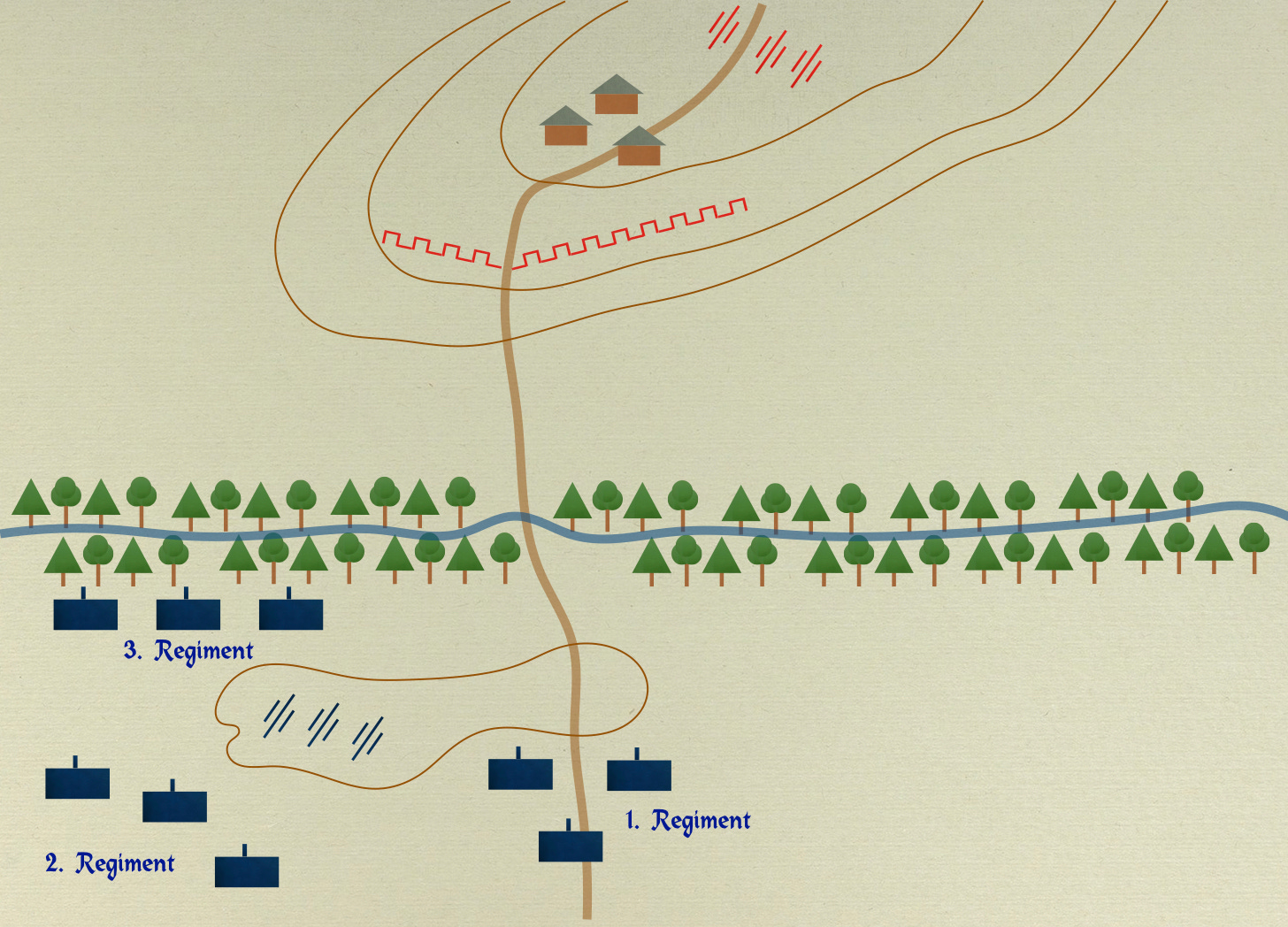

We were on a gentle slope, which rose gradually towards our left, and was crowned by our artillery. About 550 yards to the front of this slope, flowed a brook in a trough-like hollow. On our side, the bank was covered with thick brushwood, fairly large woods, and a few farm buildings.

On the further side, the country was open. It was level for some 550 to 650 yards, and then rose gently. On the top of this rise was the enemy. On the right of our guns was a road leading across the valley towards the heights held by the enemy. The enemy’s artillery was astride of this road. It was rather retired, and its front was covered by infantry occupying shelter trenches and the houses near the road.

I was opposite the enemy’s right wing. This was posted on a broad, gently slop- ing salient, on which was a village. You could see, in front and on both sides of the village, shelter trenches recently thrown up.

Gently undulating ground lay in continuation of this wing, and was apparently commanded by the village height. This height was about 1300 yards distant from the brook. The artillery of both armies was vigorously engaged. The opposing guns were about 2200 yards distant from each other. Whenever we advanced to the attack, we should find no cover except close to the height some 700 yards from the shelter trenches.

Looking round, I saw three of our battalions standing sheltered by the height on which I was. I recognized in their colonel Hallen, who was addressing his regiment.

He had just finished announcing the punishments that would be inflicted according to the principles I have quoted from him. He now proceeded as follows:

‘I know none of you have any intention of allowing yourselves to be found guilty of such conduct. But during the night, when killed and wounded are lying around us, it sometimes happens that a few men lose their heads and forget the best intentions.’

‘It is the duty of the strong to talk to such weak men, so as to make them regain their courage and not disgrace the regiment. Should any one of you find himself losing his head or courage, he must look at his officers, and if they have fallen, there will be the sergeants and other brave men whose example will put him right again.’

‘Comrades, our duty today is to uphold the famous old name of the regiment. We have to storm the village which you will see opposite you on reaching the top of this hill. Our regiment is selected for this task. We will show ourselves worthy of this honor and of the great confidence placed in us by our superiors.’

‘Our lives belong to the Emperor. None of us has any right to his life so long as the village is held by the enemy. We will all perish before that village, or before the sun goes down it shall be in our hands. His Majesty, the Emperor, the well-being of our country, and the honor of the regiment demand this of us.’

Thereon rose a cheer for the Emperor again and again, till the mighty sound of nearly three thousand voices penetrated far and wide over the fields, even to the enemy’s position.

I saw the eyes of the men lighted by a calm enthusiasm. I thought of my first battle in the French war. As we went into the battle, which had been gaging from some hours, the colonel addressed us in these few simple words:

‘Now, men, if those over there,” pointing to the troops in front, ‘can’t manage the business, we will. ‘

A joyous cheer answered him. Our enthusiasm seemed to me the louder, stormier and more exaggerated of the two. Here, in Hallen’s regiment, the enthusiasm was quieter, more earnest and determined. The threat of punishment had had its effect. All were conscious of the gravity of the occasion, but they were also determined to show themselves equal to it.

I must own I prefer the quiet enthusiasm. It stays longer.

The Colonel (Hallen) now took the majors to the top of the hill, and gave his instructions. The salient height was to be taken first. Then, pivoting on this height, the brigade was to wheel round it to the right, and so fall on the enemy’s right flank. The work allotted to the first brigade was as follows: The 1st Regiment (Hallen’s) was to take the village, its left flank being covered by the 2nd Regiment, which would also give support if necessary.

When the village height was taken the 2nd Regiment was to complete the out- flanking of the enemy. The 4th Regiment was to form the reserve, and would move up to where the 1st Regiment now was. The 3rd Regiment, which had formed the advance guard, and was now occupying the wood in front of the artillery, was to carry the enemy’s guns.

As regards the 1st Regiment, the 1st and 2nd battalions were to form the fighting line and the 3rd the regimental reserve. The colonel carefully pointed out the objectives for the outer flanks of the 1st and 2nd battalions. With delight he called attention to the fact that the enemy’s guns had ceased firing, and that our own had now, for some time past, been shelling the village and its shelter trenches. The village was already in flames.

The two battalions were to advance without firing as far as the foot of the hill, rest there a moment to pull themselves together, then advance, and when about 500 yards from the enemy’s shelter trenches, open fire on them.

From the state of affairs, it was probable that the order to advance would soon arrive. The regiment was to deploy and prepare for the advance. Any time that might remain was to be used to explain to the junior officers the nature of the coming work; but they were not to be exposed to the enemy’s view.

The regiment now deployed. I admired the bearing of the men and the smart way in which they handled their rifles. Every movement was as if on an ordinary parade. ‘Is this peculiar to the regiment, or have the customs of our army changed in this respect? That would indeed be a step forward’, thought I.

Then a sad feeling came over me. ‘This accurate drill, these strict orders, this regularity, this front, what will it all be probably in half an hour? Chaos?’

I did not think about the loss. If you wish to conquer, you must know how to die. We are all destined to die, and there can be no more beautiful death than that of the battlefield. As I moved forward, and the solemn feeling of the coming battle came over me, I sang the old soldier song

Earth no fairer fate can show

Than his who’s slain with fact to foe.

Those on turf or heather sleeping

Ask not for they needless weeping.

In narrow bed must each at last

Alone in Death’s grim ranks have past;

While here like new-mown grass there lie,

Men at whose side ’tis well to die. So sang the mercenaries of past centuries. We who are born in an age when all alike share the common duty, we who have to defend hearth and home and national honor, the noblest possessions of mankind, allow ourselves to be put to shame by these mercenaries.

I do not know how long I had followed this train of thought. I was startled out of it by seeing that the enemy’s lines were all at once showing renewed activity. Their artillery, which had of late ceased firing, had begun again with great vigor. What was the reason of this? Ah! the 3d Regiment was, on both sides of the road, advancing against the enemy’s guns. There were five or six companies thrown forward, mostly in thick skirmishing lines. The hostile infantry in this part of the field kept up a hot fire.

‘My God’, thought I, ‘are we going to again commit the old mistake of attacking only from one side, and with only a weak advanced guard? These troops, as they will receive the combined fire of the whole of the enemy’s front, will assuredly be annihilated. Then the others will be forced to make a hasty attack, not in order to drive back the enemy, but to try to restore the balance of the fight. It would be a bad blunder, and the sure cause of disaster.’

But no; a shell from the enemy comes in my direction, and bursts 100 yards in front, on the top of the hill. At the same time I heard behind me loud cheering. This came from the firing line of the 1st Regiment, advancing over the hill and answering the enemy’s greeting. I saw, farther to the left, the 2nd Regiment also preparing to advance.

‘Ah’, thought I, ‘now the enemy’s guns will have so many targets at the same time that they will get confused; moreover, every part of the enemy’s front will have its work cut out to defend itself and will not be able to help the others. A united attack is the only way of succeeding against a united front.’

As soon as the enemy’s troops on the village height perceived the advance of the 1st Regiment they deployed thick firing lines, occupying the shelter trenches in front and on the sides of the village. Our artillery had been on the lookout for this moment. A devastating, quick, shrapnel fire burst over these firing lines.

We saw, amid the thick smoke of the bursting shells, that the enemy was becoming disordered, that many threw themselves down and that others rushed back to the village. It was only in disorder, and by the use of fresh troops that the enemy finally succeeded in fully occupying the shelter trenches.

Then the usual scene immediately presented itself. The line of little clouds of white smoke spread out and surrounded the entire height. Although the range was 1700 yards, the bullets were already whistling about our heads. ‘Let them shoot’, cried out Colonel V. Hallen, from behind his skirmishers. ‘Go on to five hundred yards distance, and we will make them sing small. The artillery will look after them till then’, he added, in a lower tone.

On observing more closely the firing line of the 1st Regiment I perceived that it consisted of single rank platoons in close order. ‘Ah! Hallen’s fire tactics’, shouted I, with joy, for my old dislike of these tactics had changed on a closer and calmer observation to interest and liking. Yes, everything was carried on as Hallen had described it to me.

The companies were divided like rifle companies into four sections.1 My friend had said to me, “If we keep to the present subdivision of the infantry company, a platoon at war strength in single rank formation would be too strong for a leader to handle. On the other hand, half platoons would be too weak. Besides which it would be very difficult to provide six officers and as many sergeants for the fire units. If you reckon a company at 250 rank and file and then deduct musicians, men on command, stretcher bearers, ammunition carriers and battle police (of these latter more anon), and finally a small percentage of sick, you will get the strength of the company about 200 for the first battle.

That is about fifty men a platoon, and that, I believe, to be its proper strength. If during the campaign the company becomes weaker you can divide it into only two or three platoons, for the number of leaders decreases as fast if not faster than that of the men. Even if, at last, the company consists only of one platoon, and that is led by a reserve officer, it still remains the company.

Our organization must not depend on the probable losses. We fight our first battle at nearly full was strength. On the result of that battle most likely depends the fate of the campaign. Our fire units must be neither inconveniently strong nor too weak.

Hallen divided each platoon into half platoons, each half platoon into three sections. Each platoon had a second leader, who, when the first leader fell, took his place. One of the section leaders was told off to take the second leader’s place if necessary. The ranks of each section had similarly a second section leader, who had in turn his man to replace him.

‘We must not’, said Hallen, ‘leave it to chance whether when a leader falls, his place is speedily taken by his successor or not. Many a man, who is neither ambitious or dashing, will take advantage of your not having settled the matter to keep himself in the background. Now a section must never be left without a leader even for a short time. Battalions and regiments can for a time dispense with leaders more easily than sections can.’

The 1st and 2nd battalions advanced side by side to the attack. Each battalion had two companies in the fighting line, and two in reserve. Of the leading companies the inner ones had each three platoons in the firing line and one in support: the flank companies had two platoons in the firing line and two in support. The firing line of each battalion was therefore about 160 yards long, and consisted of five platoons, each of which occupied a front of about 45 yards, with an interval of about 9 yards between platoons.

The leaders of the companies in the firing line were still mounted and were riding, accompanied by their company buglers about 110 yards behind the firing line. Behind followed the supports at about 330 yards from the front. They were either in one or two ranks.

The battalion reserve was in line.

All the leaders down to and including the section leaders, who were taken from the rank and file, wore whistles, of which every company took a reserve supply into the field. These single rank platoons marched and dressed by the center, i.e., by the man on the right flank of the second half platoon. This man took his direction in all movements from the section leader, who marched in front of the line.2

The direction was given either by an order from the leader as to the point to be taken up for marching on, or by the leader himself being followed. The second section leader was behind the right flank of the second half platoon and directed it. The section leaders marched behind their respective sections, and were responsible for the maintenance of close order and discipline.

To be continued …

Soon after an installment of this series appears in the pages of The Tactical Notebook, a link to it will appear on the following guide.

For more about Jäger battalions, see

In this context ‘rifle company’ refers to a company of a Jäger battalion, which was customarily divided into four platoons.

I wonder if, in this instance, ‘section leader’ refers to the leader of the ‘platoon’ (Zug) rather than the leader of a squad (Gruppe).

Autopsy or suicide note?