This is the sixth post in a multi-part series. To find other installments, please consult the following guide.

Arnold was one of the best men of my company. You might trust him with your life. He was touchingly subordinate. He was a pattern soldier, a splendid shot, and a good patrol leader. He would have made an excellent sergeant but for his weak character.

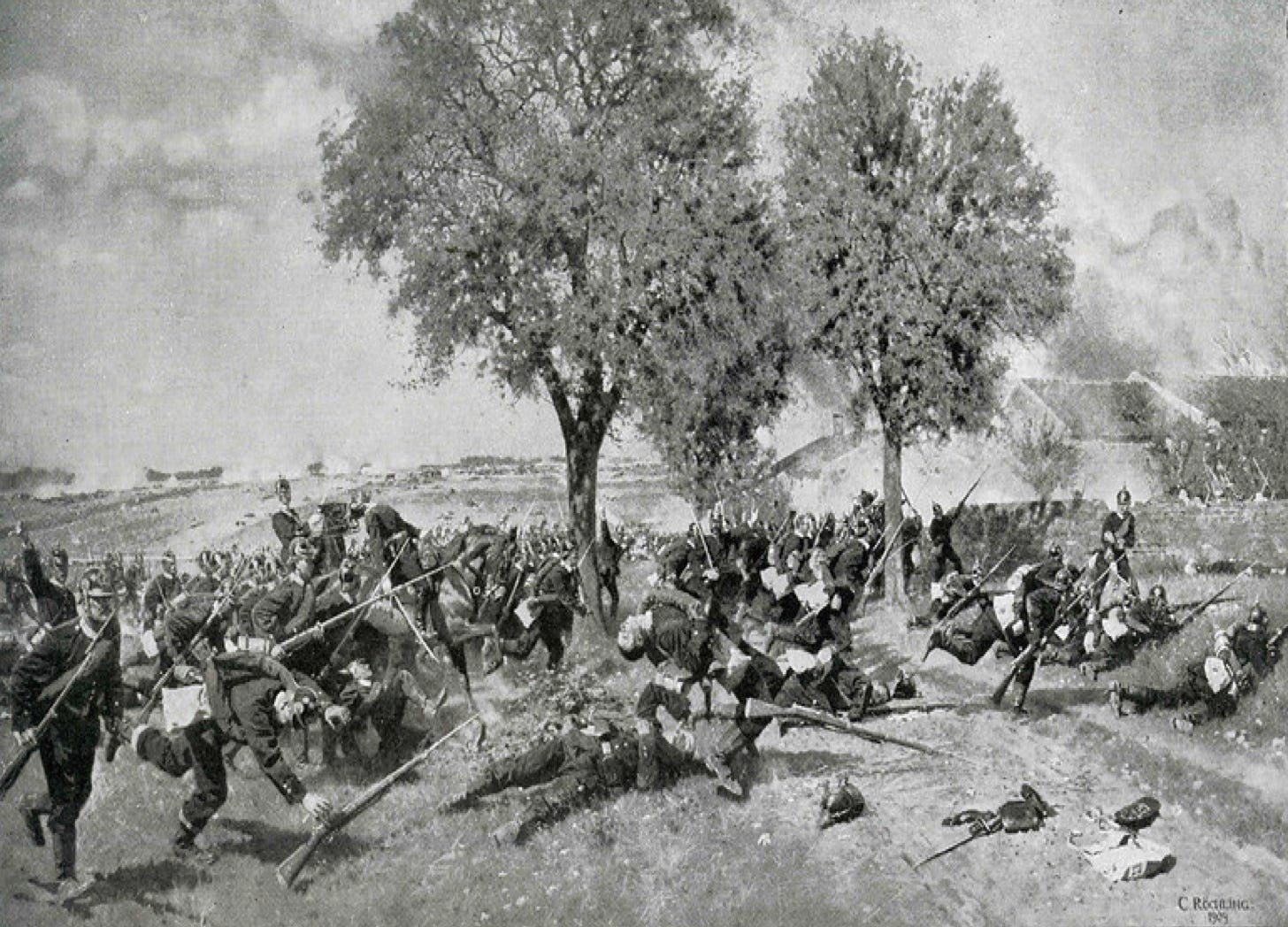

We were opposite to and about five hundred paces from an extended position of the enemy, and under a brisk fire. My entire company had by this time been necessarily extended. With dismay, I marked the growing uneasiness of my men without being able to do anything to stop it. Every one was lying down and firing. I could see rifles whose stocks never left the earth.

The upward direction of the muzzles was particularly noticeable at one part of the line. On looking closer, I could see that there was a little rise in the ground in front which prevented the men from seeing the enemy. This did not, however, stop the men in question from firing away as hotly as the others, and sending all their bullets over the rise into space.

To my great astonishment, I saw among these madmen Lance-Corporal Arnold.1 Full of anger I rushed at him, seized him by the shoulder and shouted ‘What are you shooting at? You can’t see the enemy.’

Not feeling certain that amidst the noise he understood my words, I accompanied them with lively and unmistakable gestures. Arnold looked round, but his gaze was vacant. Clearly, he did not recognize his own captain. Then, hearing a few shots whistle close by us, he flopped down again to fire harder than ever.

My anger got the better of me. I hit him with my sword so hard over the helmet as to make a great dint in it, and to knock it off his head in spite of the chin chain. This had an effect. The man sprang on to his knee as if struck by lightning. His face was deadly pale, and every limb was quivering.

I could not understand what he said, but from his face I saw that he now recognized me. Never shall I forget his look, partly pleading, partly reproachful, like the look in a stag’s eye when the hunter approaches to cut its throat.

He fell down again all in a heap, as though crushed, his eyes staring at the ground. This, however, lasted only an instant. He jumped up quickly, grasped the arms of the men nearest him, and encouraged them to advance with him to the place I had indicated. As his comrades did not understand him at once he crept forward alone, and although endangered by the wild fire of the men who remained behind, commenced a steady, well-aimed fire from the rising ground.

After having with trouble and by forcible means, induced the other men to move up to where Arnold was, I went off to the other flank of the company. I never saw Arnold again; he fell in this fight. ‘Poor man,’ thought I, ‘what a parting after you had been for full two years and a half my most faithful, dependent and hardworking subordinate!’

This is the evil result of fighting in crowds without leaders. The best men fall victims to bad examples. It seemed to me now as if I saw Arnold deadly white and with that last beseeching look, standing before me. ‘Ah,’ said I, ‘how could you, a first- class shot, an excellent patrol leader, thus forget yourself so far as to loose off your cartridges into the sky?’

‘Oh Captain,’ he answered in his soft voice, ‘forgive me. I did not know what I was doing. I was not myself.’

‘But you had learnt, and learnt better than others, how a soldier should behave in action. You should have been an example to the others.’

‘Yes, Captain, and I wanted to be such; but if you see the others get wild, if shots are sounding in your ears from all sides, if the bullets are whistling close past you, and you see comrades falling maimed and wounded around, you, too, yourself bleeding, grow wild and forget everything you have learnt. If we could have only seen the Captain now and then, and heard his orders, things would not have become so bad; but the perpetual rattle of the shots made us deaf and stupid.’

‘At first, I would not allow this wild shooting at any price. I knocked down Hartman’s rifle because he was shooting into the sky. I put Krepps’ sights right, on finding him shooting at 600 yards with his flap down at point-blank range. But all this was no good. One set the other off, and so the firing became wilder and wilder. When the noise became so bad and the smoke so thick that you could not see your hand before you; when Krepps was hit by a ball and began to yell, when Schuhmacher, who comes from my village, and with whom I went to school, was hit in the head, fell and looked up at me with the glassy eye of death; well, then I could neither see nor hear, and what I did I cannot say.’

‘But when the captain hit me, I became miserable, so miserable that I wished to live no longer. I wanted to keep on running towards the enemy, all by myself, but the others held me back. After a little, I saw that the enemy was shooting less and that on the flank where the captain was the fire was getting weaker.’

‘“Where is the captain?” I shouted.’

‘I ran to the left, always asking the same question as I went, till some one said that the captain had gone forward. Then I ran back as hard as I could to the others, and said, “We must push on. It would never do for us to let the captain be by himself.”

‘They said, however, that they did not know where the captain was and did not care either. Only Klasing and Meyer said they would come with me. Then a great fear suddenly seized me, “If the captain should think you meant to stop behind!”

‘“I’d rather be killed”, thought I. “Come along after the captain”, shouted I, and I ran and the other two ran after me.’

‘We reached a firing line of our people, belonging to another regiment. I thought I had come too much to the left, and turning to the right went along the firing line; but I came across only strangers. At last we reached the end of the line; but farther on, amongst some bushes, I thought I saw firing and ran towards it. Suddenly fire came from right and left. We were between friend and foe. I felt I was hit, and fell, and know nothing farther.’

‘Brave man!’ I exclaimed, ‘I knew you would be true to death. How it pains me to think that I had to embitter the last hours of your life by rough treatment. But you had a fine death, and your memory shall ever be held in honor.’

While still much affected by these sad recollections, I suddenly again heard my friend’s sonorous voice.

‘He who fires, when in the ranks, without orders will be severely punished; so also will the man he punished who throws himself without orders on the ground, or without orders uses his magazine.’

‘Every soldier who fires without aiming, who uses the wrong sight, who spoils a volley by pulling his trigger too soon, or does not instantly stop firing on the sound of the leader’s whistle, will, after the fight, be reproved before the assembled company, unless he has afterwards atoned for his mistake by distinguished conduct.

‘Whoever is found with an empty or partially empty magazine must explain the cause of this; and should he be found guilty of having neglected an opportunity for refilling it, he will be severely punished.’ 2

‘Whoever is found without permission in rear of the fighting troops alone, idle, and not wounded, or who without orders carries wounded men out of the fight, will be tried by court-martial for leaving the ranks. Should he not be a private, he will be punished more severely in proportion to his rank.’

To be continued …

Soon after an installment of this series appears in the pages of The Tactical Notebook, a link to it will appear on the following guide.

I suspect that Captain Gawne is using ‘lance-corporal’ as a translation for the peculiarly German rank of Gefreiter.

Note the presumption that, under normal circumstances, a soldier should treat the five rounds in his rifle’s magazine as a reserve and that, under normal circumstances, he should load each round that he fires into the chamber by hand.