This is the seventeenth (and last) post in a multi-part series. To find previous installments and those that follow, please consult the following guide.

It was already broad daylight. I dressed and hurried into the veranda to cool my hot head in the morning breeze. The birds began their morning carol. The air was invigorating. The rising sun was spreading its beams over the eastern sky.

I was under a kind of spell. My mind was filled by my subject, and by the elevating pictures of death-despising obedience, of magnetic leadership, of unbending severity and the indestructible power of close order. I was in a dream. It seemed as if all of this had actually happened.

It was not the first time that my spirit, enthralled at a late hour by subjects that had excited strong emotions or deep thoughts, had gone on working during the night, and whilst I was passing from dreamy coma to quiet dozing had grasped what it was working on with such power of decision and of drawing conclusions as is not always at my command during the day.

In this way I once solved a mathematical problem over which I had in vain racked my brains till late into the night. But the power which my dream exerted over me to-day in waking hours was something astonishing. Was it enthusiasm for the subject, or the charm of my good old friend’s intellectual and personal influence?

I sat down in the place where, only a few hours ago, I had listened in astonishment to Hallen’s words. What a revolution had been effected in my ideas and temper during the few night hours.

I made the lifelike pictures pass once more before me in every detail. My success in the foregoing pages, in depicting the truth conveyed in them, has, I fear, been small.

Shall the thoughts which my gifted friend has tested for years with all the force of his piercing intellect, which he has found to be without flaw - though the truth of which has so convinced and mastered me shall these thoughts be buried and allowed to rot as if they were useless and hurtful? Are Hallen and I men who allow ourselves to be guided by still-born creations of the brain? Is not the subject of these thoughts a weighty one for the army? Is it not worthy of the thought of others? Yes, to all!

Is the fact that the views which are now popular are against us a reason for silence? Certainly not. It is the duty of any one who is as thoroughly convinced as I am to speak out, and I will speak, and Hallen must allow me. Oh, if I could but inspire my pen with the enthusiasm which fills me! Could I but convey in words my friend’s persuasive charm, which conquers me so quickly; could I but call to the aid of my waking and thinking state the phantasy which was at my control during my dreams, then I should be certain of success.

But what need of artifices? The principle itself shall and must win.

When this resolve stood firm and clear before my eyes, a tranquil feeling came over me. My spirit became clear and calm. With the morning breeze playing about me, I fell into a deep slumber.

‘Dear Hallen’, I said to my friend, as we met at morning coffee. ‘Your wish is fulfilled. I have thought about most seriously over matters which you disclosed to me last evening, and -’

‘What, said Hallen, astonished, ‘during the night! Were you not able to sleep?’

‘Well, not over well. Hadn’t you been exciting my brain?’

‘Ah, yes. I forgot; you have the enviable gift of solving problems in your sleep. Have you been doing this last night? And have you arrived at a decision?’

I winked, laughingly.

‘Don’t be angry’, said Hallen, as it seemed to me for the first time a little crossly, ‘but although we all know an uneasy midsummer night’s dream may bring forth many fine things, still it is new to me, and scarcely credible, that it can be a trusty guide in weighty tactical questions. It hurts me’, he continued, seeing me still smiling, ‘that you should so lightly brush away matters, which I have carefully thought over for years. Let us talk them over this evening, and I hope I shall be able to show that your disparaging criticism is a little hasty.’

‘Disparaging criticism!’ The astonishment was on my side now.

‘Disparaging criticisms are always quick and easy’, said Hallen; for agreement, time and trouble are necessary. A man must either be thoroughly acquainted with the ideas on the subject, or, if they are quite new to him, as mine were yesterday to you, he must not grudge the trouble of mastering those ideas.’

‘But, Hallen’, said I, ‘I do not in the least mean to disparage your ideas. I am on your side. The few hours of the night of thoroughly convinced me of the truth of what you said. My dear fellow, what I night I have had! I went to bed full of our conversation. I did not sleep for some time.’

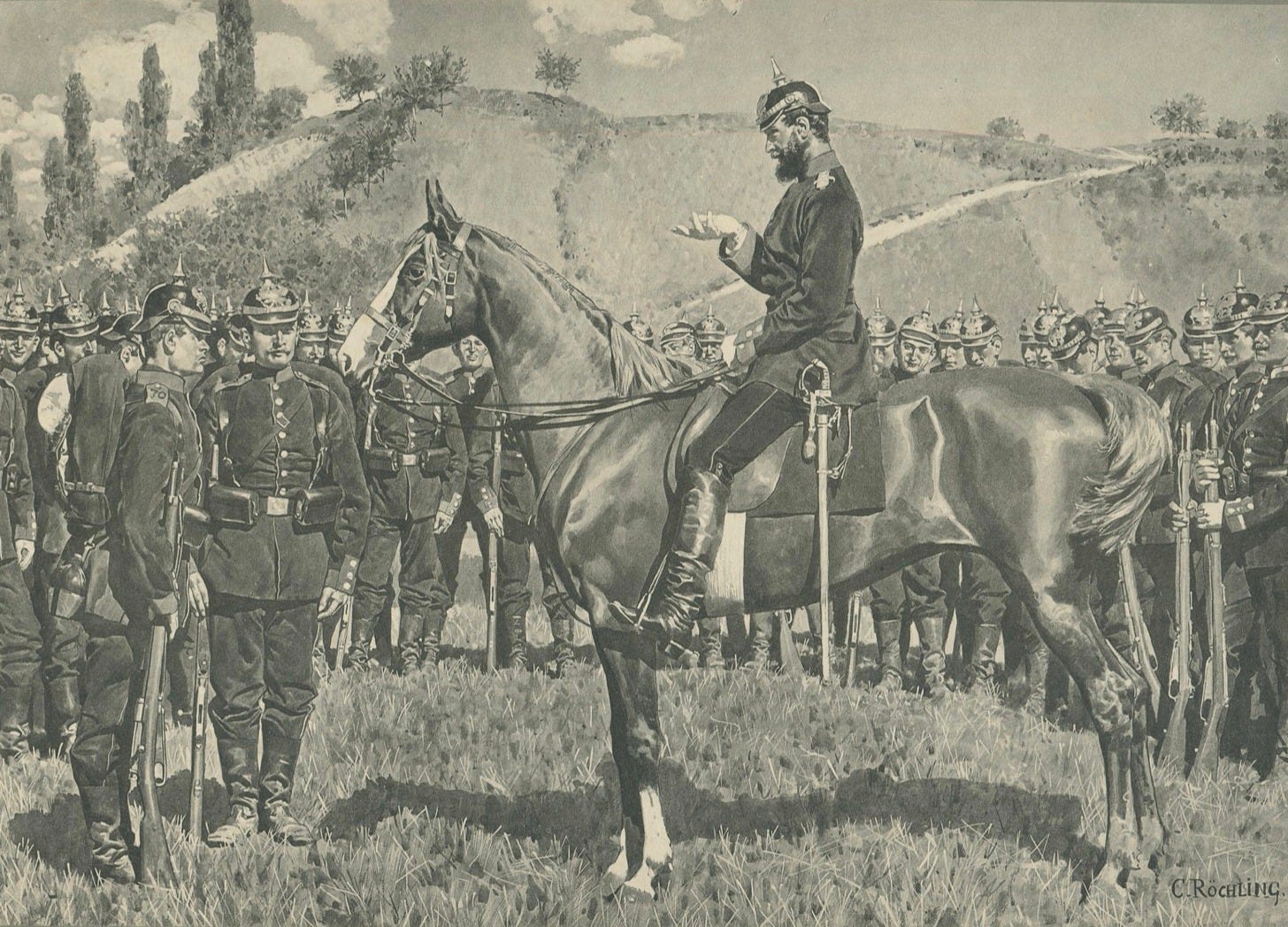

‘The more I thought over your ideas, the more I liked them. And when I fell asleep I had a dream. I saw you and your regiment in action. I saw you storm a height. I saw you execute everything you had but just explained to me. There was no longer any necessity for my brain to convince me of the enormous advantages of these tactics. I saw them, with my own eyes, embodied in you and your brave men. This effected me more than months of reflection could have done.’

‘That beats everything’, said Hallen, as his face cleared and he grasped my hand.

‘Yes’, I continued, ‘in three hours I have gone farther than you have done in three years. I am a stronger adherent of your ideas that you yourself; for when the sun rose, I was firmly resolved that they should be given to the world.’

‘Tell me first what you saw and thought’, said Hallen.

I did so.

‘It is wonderful’, he said, laughing, ‘and you are still in ecstasy, as if you had seen a miracle.’

‘Just so. It seems to me like an inspiration, which keeps on urging me to publish it.’

‘My dear friend’, said Hallen, ‘don’t be impetuous. You are still full of your dream. After you have thought over it for a few days, you will see that the present time is not ripe for the disclosure of such ideas. General opinion is against us, and our tactics are not quite ripe.’

‘You may take my word for their ripeness’, I answered. ‘You know me to be no friend of unripe fruit. It does not follow that because current opinion is against us now, it will remain so. Your disclosures were like the egg of Columbus to me, and very likely will be so to many others.’1

‘This matter’, remarked Hallen, ‘will not cause every one an uneasy night and result in inspired dreams. The majority of men do not like being torn by astounding revelations out of a world in which they have ensconced themselves comfortably. No, they will turn away from the new idea and remain as they were. Remember also that all those who write about tactics, or are accepted critics, i.e., the leaders of the prevailing views, have to a certain extent staked their position and influence on the present ideas. You yourself would have nothing to say to my disclosures. You have only been brought to a more favorable judgement by your friendship for me, by your uncommon imagination and by the speed with which you assimilate another’s thoughts - at least mine. Where such ideas fail, my ideas will be scouted.’

‘Oh, Hallen, you take too gloomy a view of the matter. Certainly you will not succeed at once, and one word will not be sufficient; but if there are to be words over it, there must be a beginning. Let there be opposition, so much the better. You do not think your scheme perfect yet. Good. In the general exchange of views it will be further perfected.’

‘Opposition was what I had expected from you’, said Hallen. ‘I wished to test the strength of my argument by your objections. As it has turned out otherwise, we shall have together to stand out against universal opposition. I am not yet ready for that.’

‘I have no fear that the opposition will be difficult for senior officers to agree to our theories. They have been brought up on the real dispersed fight. All that they have thought and done is connected with the dispersed fight. Just as we scarcely notice the change effected by time in a man whom we see every day, so that change which has come over the essential character of the dispersed fight in the course of years, has for the most part been unnoticed by these officers.’

‘For us seniors the dispersed fight is everything, as I remarked to myself last evening. But on the other hand, with service increases the desire for discipline and order. This will greatly help to induce some to uproot, by the aid of reason, the deeply-planted effects of custom. I am not afraid of the young generation. It has grown up in the tactics of the conflict of principles, as you designate the modern infantry tactics. The seed of doubt has been sown in each breast with the primary military education, and from this seed the flower of knowledge can be easily unfolded. The majority of the junior officers will prefer to have clearness, and the prospect of a definite standard as to their duties, to a puzzle. The lieutenants will gladly exchange the leadership of a swarm of skirmishers for that of a single-rank platoon in close order.’

‘Will many take kindly to a lesson’, said Hallen, ‘which differs so widely from the Infantry Drill Regulations?’

‘The Regulations’, was my answer, ‘in any case require revising, whether the decision be for the tactics of organized disorder or for close order. Even if it is decided to choose the middle course, represented by the present infantry tactics, and to cast these in a uniform mold, still the Regulations must be shaped afresh.’ 2

‘But our proposals would require the most radical changes’, replied Hallen. ‘The entire dispersed fight must be struck out and the education of the man in the single fight - I mean the isolated fight (battle duels) - must be placed in the Musketry Regulations and the Instructions for Infantry Outpost and Reconnaissance Duties.’

‘Even if the carrying out of our ideas required the greatest possible number of changes in the mere wording of the text books, our views yet approach the spirit of the old Regulations more closely than any others do’, I answered.

‘In any case an alteration of the Regulations is a long way off’, continued Hallen, ‘as, in the first place, you must have a good foundation to build on. Who can say positively that that is possible till after a new war? How thankful we should all be that the highest authority has hitherto opposed all demands for new Regulations. What should we say now if we had issued in 1874 as permanent Regulations the ‘rain worm’ formations? Before new tactics are embodied in Regulations they should have been brought to maturity by practical trial in the field. Otherwise, people will say that one of the obstacles to the carrying out of our plans will be the lack of an enormous number of capable leaders and the substitutes required for them.’

‘To that I reply’, said I, ‘that the necessary number of leaders will be forthcoming, when once our tactics are recognized as the right ones.’

‘Besides which, I fail to see why the duties of squad and platoon leaders in the dispersed fight should be easier and simpler than those of squad and platoon leaders with close-order platoons. It seems to me less difficult to keep together a platoon in close order than to lead an extended one. In the dispersed fight, the duties of the leader are less recognized than they ought to be. That is a defect particular to this method of fighting. For instance, is sufficient care taken in practice by army custom or regulation that a leader on whose work so much depends is retired as soon as is unfit for his duty?’

‘Our last war has accustomed us to place almost no value on the influence of the squad leader in the fight. In the regimental history of the 2nd Guards, a sergeant is mentioned with praise for having corrected the sights of his men when under fire. If such a fact was extraordinary, what must have been the conduct of other squad leaders? Would it not be better, under such circumstances, to place all non-commissioned officers in the ranks, when we should at all events reap the benefits of their superior musketry education?’3

‘Let our fire tactics be what they may, the numerous augmentations which mobilization would cause compels us to use every effort to increase our sup- ply of capable leaders. With this object we must raise the position and increase the authority of the non-commissioned officer. That will justify us in making greater demands on his capacity for leading.’

‘We must also select and educate our reserve officers with more care. It is impossible to avoid extending the length of service of our one-year volunteers.4 The number of subalterns must be increased without lowering their quality. But we can go into these matters more thoroughly another day.’

‘What do you consider the best tactics for the Landwehr?’ 5

‘For very obvious reasons, the Landwehr is more sensitive than the field army to the disadvantages and dangers of the dispersed fight, and require even more holding together’, I answered.

‘The unanimity of our views is extraordinary’, exclaimed Hallen, with a gratified face. ‘If you recollect how diametrically opposed we were over the same matters but yesterday.’

‘Very well, have your way’, he added, after a pause, ‘write the thing and give it to me to read. If then our ideas coincide, we will publish it, let the consequences be what they may. The intention is good.’

That is how these pages came to be written. They are less concerned with the brilliant course of the last war than with its unpleasant reverse side. They will disgust many of my kind readers. To these I apologize. Many others, however, will think with me that the discussion of such matters is unavoidable if you want to realize frankly the many dangers and calamities that arise from want of leadership in modern war.

Though those last will possibly not agree with my views, I nevertheless venture to hope that I have not failed to excite their interest by what I have said, sufficiently to repay them for the trouble of reading these pages. If so, their being interested will amply repay me for my pains.

But I must candidly admit that my aim is higher than this. I wish to co-operate in bringing the tactics of my arm once more into conformity with the salutary spirit of order, and to restore again the shaken faith in thorough leadership. I wish to awaken those in authority to the necessity for striking out a new path which, utilizing our national traits, will again make the German infantry superior to all others.

Perhaps my aim is too high, and we shall continue to think that our good order, our incomparable discipline, and the influence of our unrivaled corps of officers will and can be of no avail in future wars; in such a case, kind readers, look on the contents of this little book as nothing more than — a pleasant dream.

The End

Soon after an installment of this series is posted to The Tactical Notebook, a link to it will appear on the following guide.

Once, at dinner, Christopher Columbus challenged his companions to stand an egg on one end. After the latter failed to do this, the famous explorer tapped the tip of the hen’s fruit on the table, thereby providing it with an end flat enough to prevent it from wobbling.

Marvelous to say, the Prussian Army of the years between the end of the Franco-Prussian War (1871) and the publication of A Summer Night’s Dream (1888) employed a set of infantry drill regulations that had been adopted in 1847. (You can find a copy of the edition of this book published in 1876 on the website of the Münchener Digitalisierungs Zentrum.)

At this time, non-commissioned officers served as ‘file closers’. That is, rather than serving as squad leaders, they occupied posts behind the lines composed of privates and lance-corporals.

Reserve officers began their careers as ‘one-year volunteers (Einjährig-Freiwillige)’, young men of the educated classes who paid for the privilege of serving but a single year ‘with the colors’.

Composed largely of men in their thirties with little in the way of recent military training, the Landwehr provided formations that assisted the field army by guarding lines of communications, occupying territory, and providing the garrisons of fortresses.