In the spring of 1911, La Gazette de l’Armée published, in four pieces, an article on the subject of war games of the type played at that time in the armies of the German Empire. The text that follows translates, verbatim, the second part of this disquisition.

In war, as in bridge, there are four trumps (time, space, fire, and movement) and a no trump (moral forces). There are two ways to play: with opposition, which is common today, or without opposition, which has largely gone by the wayside.1 We have abandoned the prescription, found in the Military Regulations of 1738, that requires the French soldier to submit to the first volley of enemy fire, and, thus, I am happy to say, are free from the good manners displayed at Fontenoy.2

In both games, there are honors (leadership, the quality of troops, cooperation between units, speed, surprise) and fortunate impasses.3

In bridge, a ‘no trump’ bid works well in an ordinary game. In war, moral forces predominate, and the offensive leads to decisive results. In both games, two things matter: the request and the way we play.

The Request

We set the trump after seeing our cards. We choose the way we fight after examining the situation. Thus, even though our doctrine preaches the offensive, there will be situations in which it makes no sense to rush forward.

In some cases, we will find ourselves holding a low-ranking card, losing men like the cards of a bad hand, and we see no alternative to persist and wait for a better turn of events.4

The request owes much to habit and good sense. We soon learn to do it with ease. This is what happens when we train. We present ourselves with a game, a situation. Each player prefers a different trump card. One wants to march, the other to shoot, a third to wait, and so forth.

At times, this tendency indicates that we have made little progress in our training. More often, it tells us that the situation is far from clear.

Here’s an example. The point of an advanced guard sees soldiers on foot, who appear to be dismounted enemy horsemen, in the distance, crossing its path. What should one do? The best say to themselves, we need to get a good look, clear the road, and get close to the horses. In short, the decision can be reduced to ‘the advanced guard will attack! Follow me!’

In truth, many important aspects of the problem have not been properly described. Lots of things often found in reality - the nature of the terrain, the conduct of the enemy, the relative strengths of the forces involved, considerations of space and time - all things that are often found in reality - will determine whether it is better to march, to shoot, to wait, to take shelter, or to rush forward with audacity.

The problems we engage in peacetime tell us much less than we need to know. With a little thought and some imagination, we can find similar situations, but never real ones. Bad weather, hunger, lack of sleep, excessive fatigue, rounds that fail to function make us neither fearful or weak.

We should not try to avoid these complications. After all, we can only make progress if we introduce difficulties, albeit in a gradual way. After all, you can’t learn to fence if you limit yourself to padded swords.

The thing to do is to avoid losing time going back-and-forth about the choice of fighting methods.

Too often, the instructor strains his imagination in order to create situations that resemble riddles.

The student shoots, marches, makes a decision, without understanding what is wanted from him.

It is, after all, difficult for a man to realize, at first glance, what another has in mind.

Sometimes he figures things out. In any event, he will look for reasons to justify his course of action.

Discussions that some people believe to be instructive often ignore the initial situation and the goal at hand. Thus, the exercise ends with a fool’s errand that both exhausts and frustrates, a flight of imagination on the part of the leader, and the training of subordinates to quibble.

In war, as in bridge, the challenge has less to do with the choice of trump card than with the way that one plays the cards in his hand.

The Way to Play

Deeds, not words.5

The instructor passes out the ‘cards’. The student looks at his hand and makes his decision. The instructor explains what the enemy does, and adds the actions of friendly forces.6 Little by little, the game unfolds.

The instructor explains but half of what he knows. He has no need to make a speech. Neither must he strain his powers of imagination. He calls for decisions and points out faults.

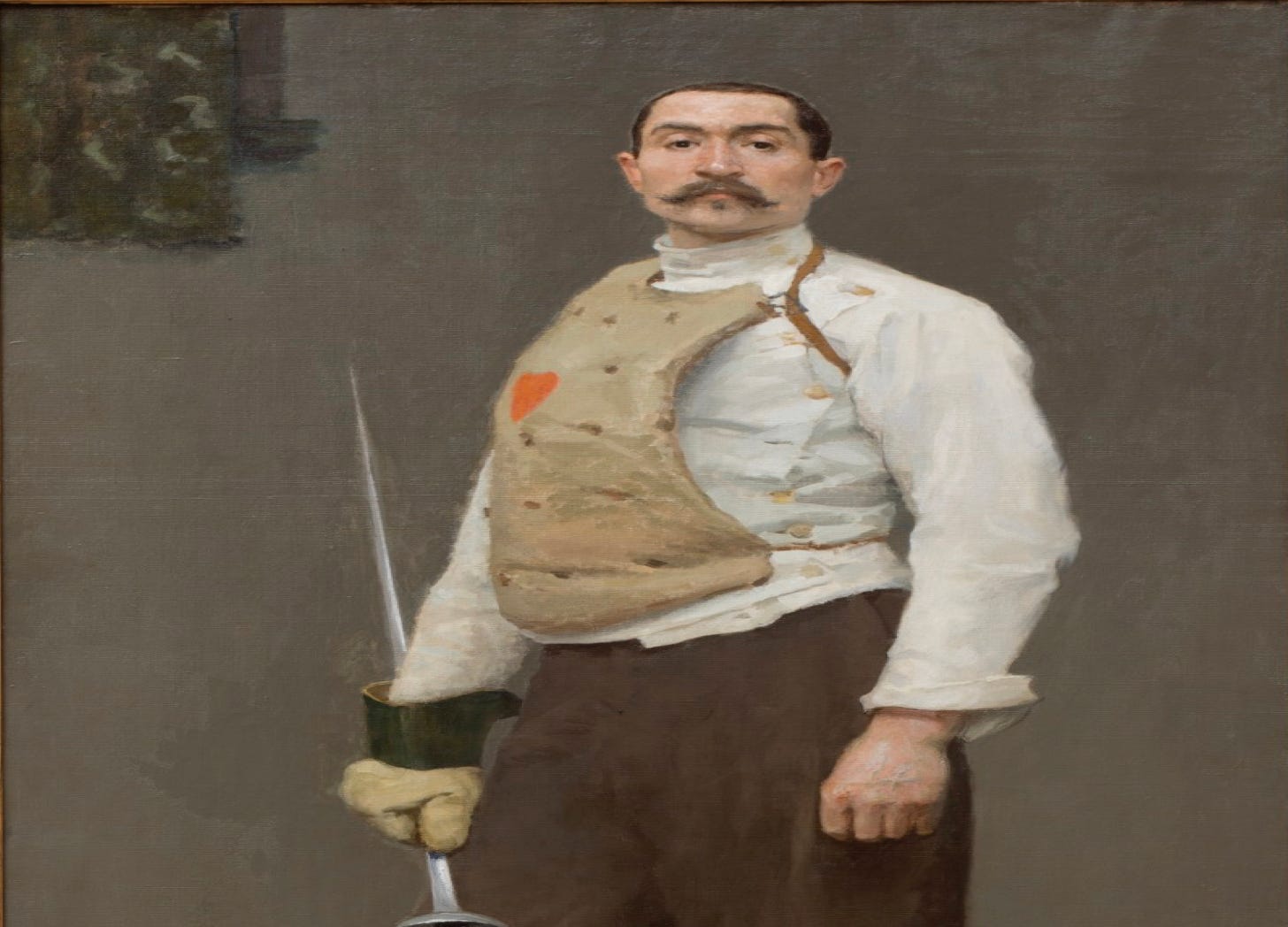

He does much the same thing as the fencing master who is as likely to open himself to an attack as he is to cut off a button.

Tact, attention, and patience are all he needs.

Having started this way, the lesson follows, step by step, the progress of the student. It is interesting for both he who teaches and he who learns. It is truly a game.

When taught in this way, the degree of learning that takes place depends upon the student, the teacher, and experience. It is not a matter of following a set lesson plan. We can always improve our instruction. He who has served for thirty years has something to learn. The task at hand is simply a matter of having soldiers and leaders who are better trained than those of our neighbor.7

To be continued …

Source: Anonymous: ‘le Jeu de la Guerre’ la Gazette de l'Armée (27 April)

For Further Reading:

At the battle of Fontenoy (11 May 1745), a British officer famously invited his French counterpart to deliver the first volley. The latter responded with ‘Messieurs les Anglais, we never fire first. Fire yourselves.’

Here, the author seems to refer to a Gallic analog of the German Auftragstaktik debate of the 1890s, which hinged on the question of whether the tactics of large units (such as regiments or brigades) ought to follow preset patterns or be custom tailored to the situation at hand.

In bridge, honors are high-value cards: the ace, the king, the queen, the jack, and the ten. An impasse is an attempt to play for time.

The expression translated here as ‘low-ranking card’ - pique de misère - literally means ‘spade of misery’ or ‘miserable spade’.

‘Deeds, not words’ translates the Latin motto res, non verba.

A literal translation of the French original of this sentence would be ‘he adds the “dead man”, that is, the part played by comrades’. In other words, the instructor describes the actions of what present-day people might call ‘non-player characters’.

The neighbor (le voisin) in question seems to be ‘the neighbor on the far side of the Rhine’, that is, the Germans.

“When taught in this way, the degree of learning that takes place depends upon the student, the teacher, and experience. It is not a matter of following a set lesson plan.”

Excellent advice, particularly with respect to eschewing a static and doctrinaire approach to learning. However and based on the way things unfolded in 1914 (and into 1916?), it would seem that the French did not follow this approach to learning. Did they have bad teachers or perhaps they were blinded by their doctrine of Attaque à outrance (not that anyone else did a whole lot better ☹️)

It is also interesting that there is no mention of the other trump card - Logistics (which acts as a brake to any campaign).

Thanks for another interesting and informative article.