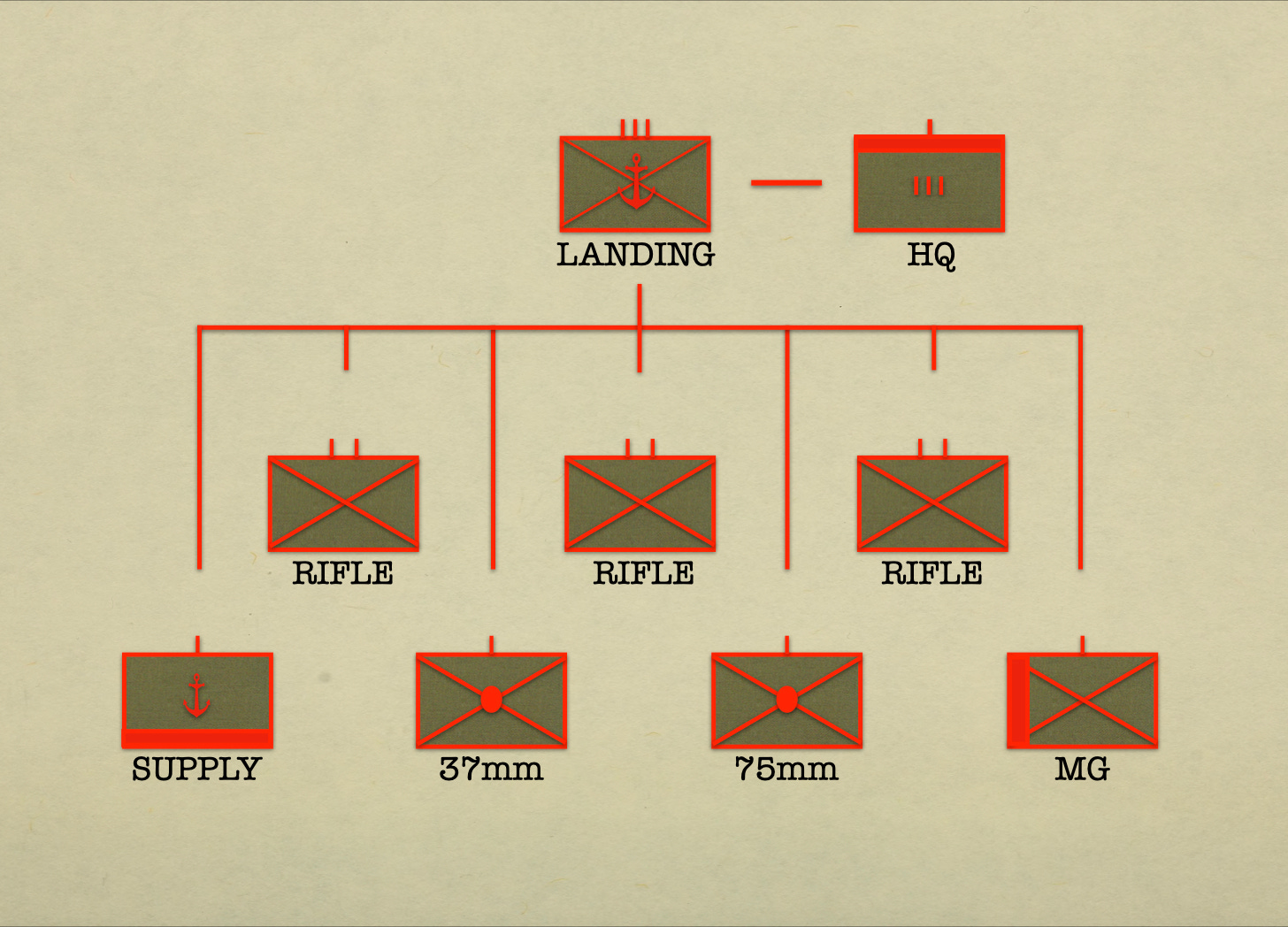

The Landing Regiment of 1921

Imaginary Armies

In 1921, in a study called Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia, Earl Hancock Ellis of the American Marines described an organization optimized for the task of seizing well-defended islands in the Central Pacific. While Major Ellis imagined that this ‘landing regiment’ would employ such artifacts of the World War as poison gas and rifle grenades, he provided it with an establishment that owed as much to the pre-war regiments of both the US Army and the Fleet Marine Force.

Both the US Army infantry regiment authorized in May of 1917 and the landing regiment sketched by Ellis possessed three relatively small battalions, a headquarters company, a supply company, and a machine gun company. However, while the battalions of these two organizations, each of which rated somewhere between five-hundred and six-hundred officers and men, resembled each other, the independent companies differed considerably. In particular, Ellis provided his supply company with men skilled in the handling of boats, his machine gun company with an usually large number of machine guns, and his headquarters company with pioneers charged with using ‘wire-cutters, bolos, and explosives’ to clear obstacles.

In addition to elements that resembled those of the US Army infantry regiment of 1917, the landing regiment proposed by Ellis also possessed a ‘gun company’ armed with twelve 37mm guns, as well as another unit of the same name that operated eight 75mm guns. (While the first of the gun companies lacked any sort of precedent, the second echoed the practice, in force between 1913 and 1917, of assigning a field artillery company to the Second Regiment of the Advanced Base Brigade.)

The number of machine guns that Ellis allowed to the machine gun company of a landing regiment exceeded, by a factor of close to two, the standard for machine gun companies of the American Expeditionary Forces. (The latter carried sixteen machine guns, four of which were spare weapons that traveled with the company headquarters.) Moreover, as Ellis allowed but a hundred and twenty-five Marines to the machine gun company, the simultaneous employment of all such weapons would require the reduction of the size of each machine gun crew to three or four men.

With that in mind, I suspect Ellis imagines that most, if not all, of the machine guns of the machine gun company would be mounted on the bows of landing craft. The same seems to have been the case with the twelve 37mm guns of one of the two ‘gun companies’ of the landing regiment. (While Ellis might have imagined these as the low-velocity infantry guns of the sort that the American Expeditionary Forces employed in France, he was probably thinking of long-barreled, high-velocity pieces of the many types then found aboard warships of the US Navy.)

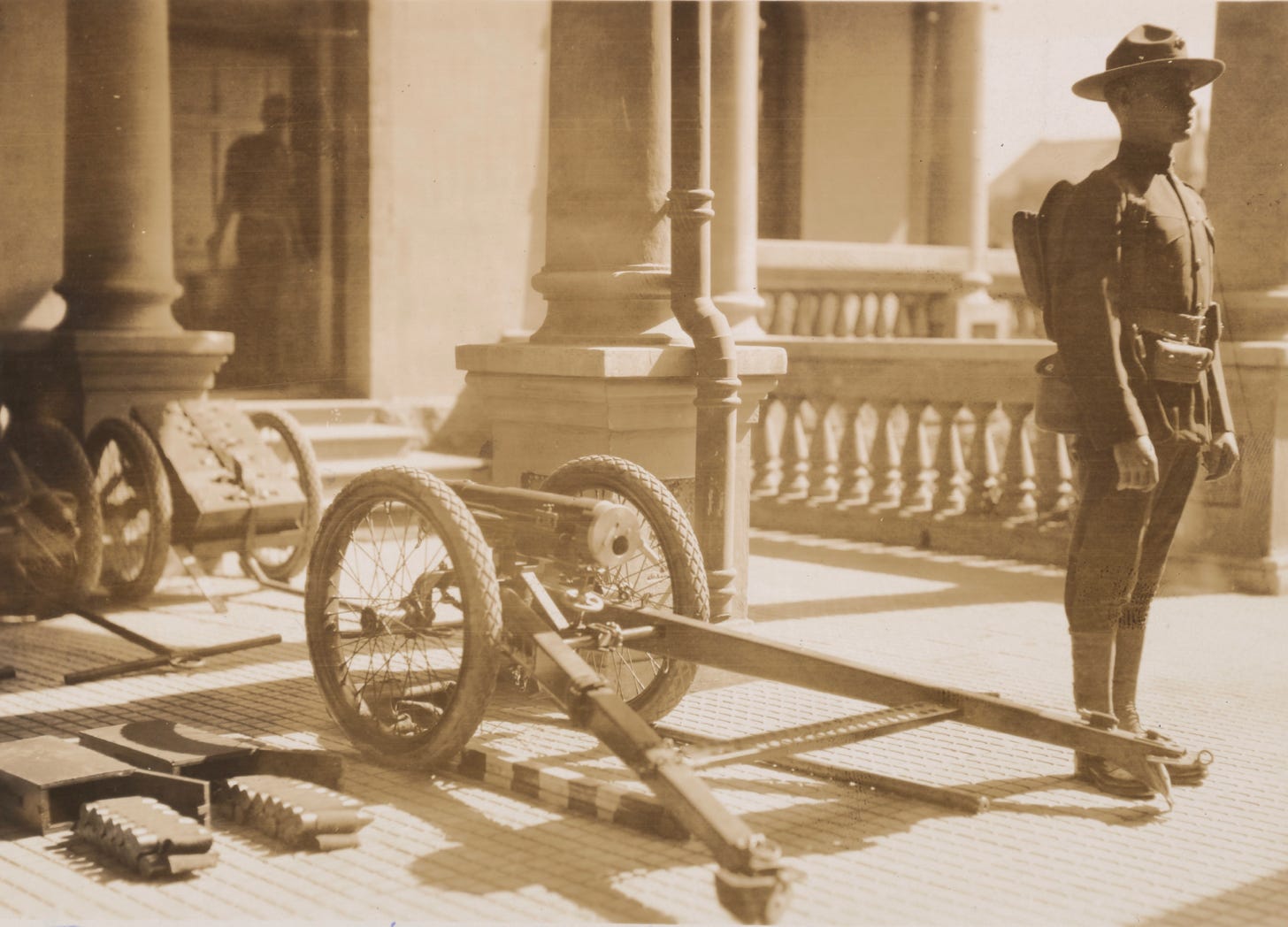

Like all of the other companies in the landing regiment, the ‘gun company’ armed with eight 75mm guns rated a hundred and twenty-five Marines. Thus, on average, the ratio of men to field pieces lay somewhere between fifteen or sixteen men for each cannon. (In a horse-drawn field battery of the contemporary US Army, each of the four field guns enjoyed, on average, the services of fifty soldiers.)

The high ratio of weapons to cannoneers suggests that Ellis imagined that the 75mm guns would be employed in the manner of the Sturmkanone of the German assault battalions of the Second World War. That is, the crews would push, pull, or otherwise manhandle their piece into a position from which it might bring direct fire to bear on an offending machine gun nest.

Source: Earl Hancock Ellis Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia (Quantico: US Marine Corps, 1991) page 50

One wonders what sorts of T/E lessons could learned/added to todays MEU in regard the machine guns and small artillery pieces. We limited only by our imaginations. As always interesting reading!