This piece concludes the two-part article begun with US Marines in the Caribbean, 1909-1911.

In the summer of 1912, the fragile power-sharing arrangement fell apart and the government in Managua found itself faced with separate rebellions in the two largest cities in the country. The leader of the first revolt was Benjamin Zeledón, who had previously served as minister of war in the cabinet of President Zelaya, while that of the second was Luis Mena, a founding member of the ruling coalition who had recently been maneuvered out of office. Once again, the US responded with an ostensibly neutral intervention that tipped the balance in favor of one side. This time, however, it was not rebels who benefited from the actions of American forces, but the national government of President Adolfo Díaz. (A former employee of an American mining concern on the Misquito Coast, Díaz had played a key role in the financing of the rebellion of General Estrada.)

The forces deployed in the American intervention of 1912, which included sizable landing parties from several warships and three battalions of Marines, were much larger than those sent out to the Misquito Coast in 1910. The task they faced, however, was much more difficult. Whereas the American forces landed at Bluefields were concentrated in that city, those put ashore in 1912 had to operate along a very large portion of the Pacific Railway of Nicaragua, a stretch of track some 190 kilometers long that connected the Pacific port of Corinto (where the American forces came ashore) with the cities of León (where Zeledón’s rebellion had broken out), Managua (which was still under the control of President Díaz), and Granada (which served as the base for Mena’s rebel army.)

At first, neither of the rebel commanders wanted to risk his forces in an attack against the Americans. Instead, each waged a separate campaign of petty harassment (which often involved damage to the railroad) and low-stakes confrontation. This, each of the rebel commanders believed, would allow his particular side to maintain its nationalist credentials while preserving its forces from the losses that would inevitably result from open hostilities. Zeledón, the more inventive of the two rebel commanders, seems to have taken this logic a step further. He maneuvered his forces in a way that suggests that he may well have attempted to orchestrate a battle between the Americans and the forces led by his competitor. Whether or not this was the case, the reluctance of the rebels to engage in open battle created an opportunity that was well suited to American purposes.

The overall commander of the American forces in Nicaragua, Admiral William H. Southerland of the US Navy, was as eager as the two rebel commanders to avoid a clash of arms. This was particularly true in the early days of the intervention, when the bulk of the forces allocated to him were still in transit and the strengths of the three contending parties were still uncertain. At the same time, Southerland was obliged to protect the American citizens in western Nicaragua (who were concentrated in Corinto, Managua, and Granada) and remind all concerned that 51 percent of the Pacific Railway was American property. To these ends, he established small garrisons at several points between Corinto and Managua, and employed a train full of Marines and machineguns to maintain communications between them. (As might be expected, this train was placed under the command of the ubiquitous Major Butler.)

For the most part, the struggle for control of the Pacific Railway was a game of bluff and bluster, with rebel leaders attempting to intimidate, impede, or embarrass Butler, and Butler making various displays of force and resolve, but little in the way of battle. The exception that proves this rule took place late in the evening on September 16, 1912, when forces loyal to Zeledón ambushed the American train near the town of Masaya. In the brief exchange of fire that followed, the Zeledónistas managed to wound five Marines while American bullets (many of which were fired by the 16 Colt machineguns mounted on the train) struck 128 of the attackers. The following morning, Zeledón sent a letter to Butler, claiming that the ambush had been a mistake. As proof of his good faith, Zeledón returned the three Marines his men had captured during the firefight.[17]

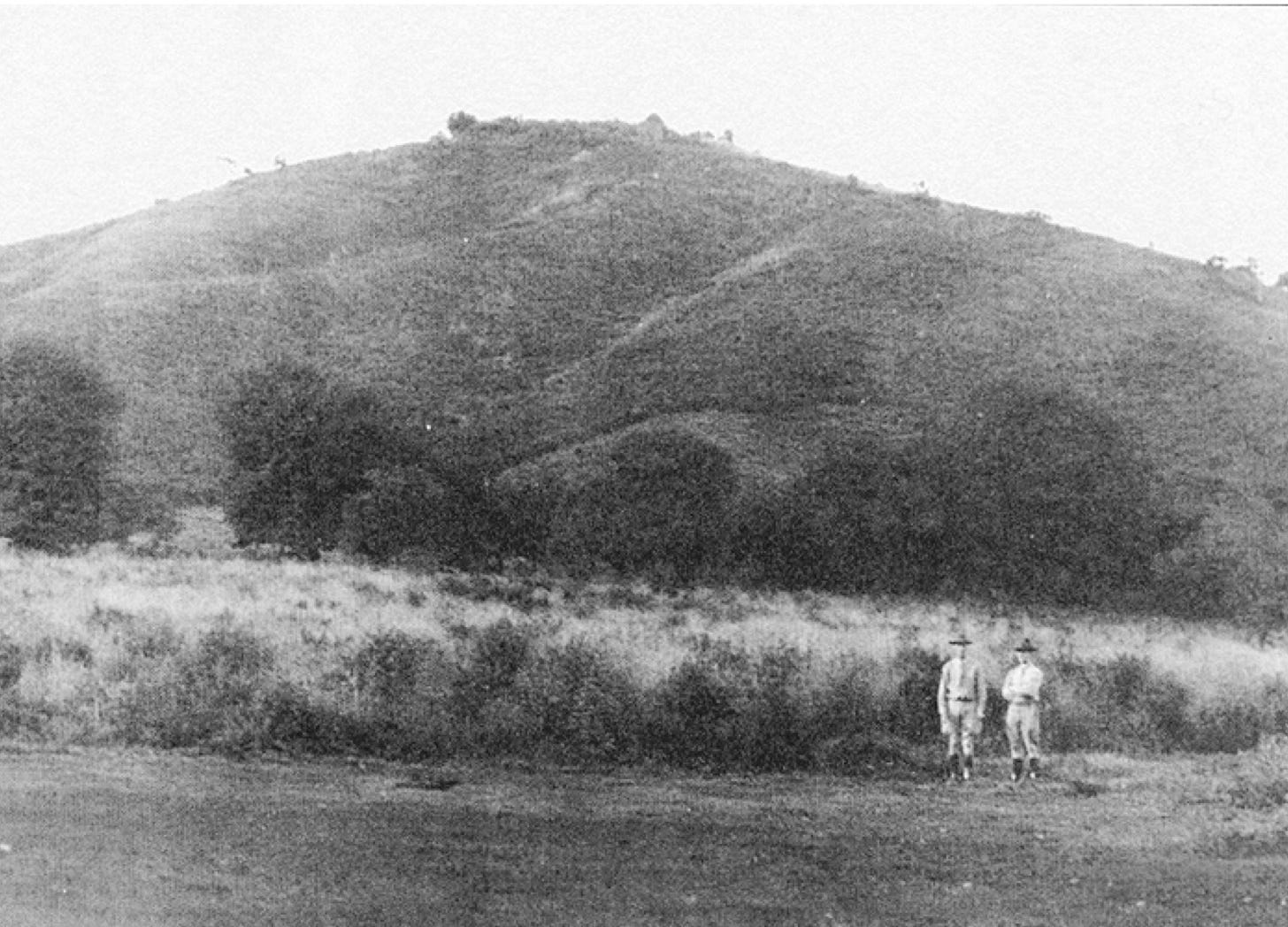

The two-month “war of nerves” for control of the railroad ended when Butler’s train reached Granada. Though he had only intended to convince the Menista rebels in control of that city to refrain from interfering with traffic on the railroad and return some American property they had seized, Butler discovered that their leader, who was suffering from a highly debilitating disease, had lost all desire for power. He therefore traded the promise of a safe passage out of Nicaragua for Mena and his son for the dissolution of the Menista army and the surrender of its weapons. Shortly thereafter, Zeledón decided that, with his chief rival out of the way and the government forces growing stronger by the day, it was time to make a stand. He blocked all rail traffic between Managua and Granada, deployed his forces on a pair of hills near the town of Masaya, and challenged the Americans to dislodge him.

In many respects, the fight for the two hills was a combat typical of the decade that preceded the outbreak of World War I, and, in particularly, bore a strong resemblance the smaller engagements of the wars that were then taking place in the Balkans, Mexico and Libya. Zeledón’s forces consisted largely of men armed with bolt-action magazine rifles, but also included a small number of rifle-caliber machine guns, several 1-pounder (37mm) guns, and three or four 3-inch (76.2mm) field guns. The Marines and Bluejackets lacked the one-pounders, but were otherwise armed in a similar fashion, with bolt-action magazine rifles, quite a few Colt machine guns and six 3-inch field guns.

The American attack began with a desultory artillery bombardment that lasted for 21-hours. This served the triple purpose of giving the untrained Marine artillerymen an opportunity to learn the rudiments of the gunners’ art, providing Zeledón with one last opportunity to withdraw his forces and preventing the Zeledonistas from firing on the Marines and Bluejackets who were forming up for the assault. Though plagued by faulty fuzes and a shortage of shells, the Marine artillerymen quickly got the better of the defenders of the two hills, causing the crews of artillery pieces and machine guns, as well as a high proportion of the riflemen, to seek shelter on the reverse slopes.

Shortly before dawn on October 4 1912, the Marines and Bluejackets began to climb up the taller of the two hills, a feature known as El Coyotepe. Because the officer commanding the Marine artillery lacked confidence in the skills of his men and the reliability of his ammunition, the American guns had stopped firing several minutes before the assault began. Thus, the attacking infantry had to rely upon their own rifles to suppress the fire of Zeledonistas, with one part of each company firing while the other rushed forward. On the whole, this sufficed to keep the defenders from making effective use of their weapons. The crew of one of Zeledón’s machine guns, however, refused to be intimidated by the American rifle fire, and managed to kill four Marines before falling prey to the bayonets of their comrades.[18]

Once the Marines and Bluejackets had taken El Coyotepe, they made use of the machineguns and artillery pieces they found there to drive the Zeledonistas off of the second hill. Once that second hill was secure, and the Stars and Stripes were seen to be flying over it, 400 Nicaraguan soldiers in the service of the Díaz government, which were supposed to have taken part in the attack upon the two hills but had somehow missed the rendezvous, burst into the nearby town of Masaya. There they engaged in a three-hour battle with the Zeledonista garrison, during which Zeledón himself was killed. Once the firing died down, the government troops celebrated their victory by looting the town.[19]

Though sporadic resistance continued for a day or two, the Battle of Coyotepe (as the fight for the two hills became known) marked the end of Zeledón’s rebellion. Within four months, the landing parties had returned to their warships and the three Marine battalions had returned to their bases in Panama and the US. Soon thereafter, the US concluded a set of agreements with the Nicaraguan government that gave the US the exclusive right to build a trans-oceanic canal on Nicaraguan territory, established a customs receivership modeled on the one adopted by the Dominican Republic, and permitted the permanent presence of a company of Marines at the American legation in Managua. Though it consisted of only a 100 or so Marines, this legation guard provided a concrete reminder of American determination to keep the peace, not merely within the borders Nicaragua, but also within Central America as a whole.

The de facto American protectorate that followed intervention of 1912 brought 12 years of uninterrupted peace to Nicaragua and its neighbors, a government that was more respectful of the rights of its citizens than any of its predecessors and a period of unprecedented prosperity. At the same time, the protectorate put the US in the awkward position of sponsoring a government that enjoyed little in the way of support traditional political elites. This situation, in turn, made it easy for anyone who opposed the American-backed government to wrap himself in the mantel of patriotism. It also ensured that self-serving warlords like Zeledón and Zelaya would enter the pantheon of national heroes and that, rather than being remembered as the last major engagement of a multi-sided civil war, the battle of Coyotepe would be remembered (at least in some circles) as the Nicaraguan equivalent of the battle of Bunker Hill.[20]

In the two decades that followed the intervention of 1912, US Marines became involved in four additional “small wars” in Central America and the Caribbean. One of these, the seven-month occupation of the Mexican city of Veracruz (21 April – 23 November 1914), bore a close resemblance to the landing at Bluefields in 1910. While the American forces landed at Veracruz were larger than those put ashore at Bluefields, and the American occupation of the Mexican city lasted much longer than that of the Nicaraguan town, both operations combined the explicit goal of protecting the lives and property of American citizens with the effect of tipping the balance in a local civil war. The other three interventions had little in common with what had gone before. In Haiti (1915-1934), the Dominican Republic (1916-1924) and Nicaragua (1927-1933), US Marines operated against forces using classic guerrilla tactics, conducted sustained counter-insurgency campaigns, formed local constabularies, and engaged in nation-building programs of various kinds. Indeed, these three occupations were so different from the Nicaraguan interventions of 1910 and 1912 that a recent (and otherwise comprehensive) book on the subject of the development of small wars doctrine in the Marine Corps in the first half of the twentieth century makes no mention of them.[21]

Strictly speaking, the Nicaraguan interventions of 1910 and 1912 do not qualify as counter-insurgency campaigns. The forces that fought against the Marines did not operate as guerillas. Neither did the Marines make any attempt to separate those forces from the inhabitants of the areas in which they operated, provide security, build local institutions or attempt to redress political or economic grievances. Nonetheless, it makes little sense to characterize the two interventions as “conventional” operations. Rather, the Marines found themselves involved in a multi-sided conflict in which direct negotiation, intricate political maneuvers, the movement of troops and exchanges of gunfire, not to mention a great deal of bluff and bluster, were intermixed in a highly promiscuous fashion.

Viewed from the perspective of subsequent small wars in Central America and the Caribbean, the American interventions in Nicaragua were transitional events, undertakings that eased the metamorphosis of the Marine Corps from a sea-going force that specialized in the work of landing parties to a land-based constabulary that had developed considerable competence in counter-insurgency operations and nation-building. From the point of view of the preceding century, however, the American expeditions to Nicaragua of 1910 and 1912 were little more than old fashioned landing operations that had been carried out on a somewhat larger scale, served a more ambitious purpose, and lasted for a longer period of time. After all, the combination of tactical maneuver with retail diplomacy had been part and parcel of the work of landing parties from the days of the Mosquito Fleet.

For Further Reading:

To Share, Subscribe, or Support:

[17]Lowell Thomas, Old Gimlet Eye, The Adventures of Smedley D. Butler (New York: Farrar and Rinehart, 1981), 154-7.

[18]R.O. Underwood, “United States Marine Corps Field Artillery”, The Field Artillery Journal, April-June 1915.

[19]Letter of Major Smedley D. Butler to Ethel C.P. Butler, 5 October 1912, in Anne C. Venzon, editor, General Smedley Darlington Butler, The Letters of a Leatherneck, 1898-1931, (Westport: Praeger, 1992), pp. 121-23.

[20]See, for example, Danilo Mora Luna, “La Batalla de El Coyotepe”, El Nuevo Diario (Managua), 12 October 2007.

[21]Keith B. Bickel, Mars Learning, The Marine Corps Development of Small Wars Doctrine, 1915-1940, (Boulder: Westview, 2001).