1. The conduct of war is an art, dependent upon free, creative activity, scientifically grounded.1 It makes the highest demands on the personality.2

2. The conduct of war is based on continuous development. New means of warfare call forth ever changing employment. Their use must be anticipated, their influence must be correctly estimated and quickly utilized.

3. Situations in war are of unlimited variety. They change often and suddenly and only rarely are from the first discernible. Incalculable elements are often of great influence.

The independent will of the enemy is pitted against ours. Friction and mistakes are every day occurrences.

4. The teaching of the conduct of war cannot be concentrated exhaustively in regulations. The principles so enunciated must be employed in accordance with the situation. Simplicity of conduct, logically carried through, will most surely attain the objective.

5. War is the severest test of spiritual and bodily strength. In war, character outweighs intellect. Many stand forth on the field of battle who in peace would remain unnoticed.

6. Armies as well as lesser units demand leaders of good judgment, clear thinking and far seeing, leaders with independence and decisive resolution, leaders with perseverance and energy, leaders not emotionally moved by the varying fortunes of war, leaders with a high sense of responsibility.

7. The officer is a leader and a teacher. Besides his knowledge of men and his sense of justice he must be distinguished by his superior knowledge and experience, his earnestness, his self-control and high courage.

8. The example and personal conduct of officers and non-commissioned officers are of decisive influence on the troops. The officer who in the face of the enemy is cold-blooded, decisive and courageous inspires his troops onward. The officer must likewise find the way to the hearts of his subordinates and gain their trust through an understanding of their feelings and thoughts and through never ceasing care of their needs.

Mutual trust is the surest basis of discipline in necessity and danger.

9. In all situations every leader must exert, without evasion of responsibility his whole personality. Willing and joyful acceptance of responsibility is the distinguishing characteristic of leadership.

This does not mean that the subordinate should seek an arbitrary decision without proper consideration of the whole or that he should not obey orders precisely or that he should let his feeling of greater knowledge take precedence over obedience. Independence of action should never be based on contrariness.

Independence of action, properly used, is often the basis of great success.

10. In spite of technology, the worth of man is the decisive factor. Its significance is increased in group combat.

The emptiness of the battle field demands independent thinking and acting fighters, who, considering each situation, are dominated by the conviction, boldly and decisively to act, and determined to arrive at success.3

Being accustomed to physical accomplishments, lack of consideration of self, will power, self confidence, and courage qualify a man to master the most difficult situations.

11. The worth of leaders and men determined the battle worth of the troops, which is supplemented by the possession, care and maintenance of arms and equipment.

Superior battle worth can equalize numerical inferiority. The higher the battle worth, the more vigorous and versatile can war be executed.

Superior leadership and superior troop battle readiness are reliable portents of victory.

12. The leaders must live with their troops, participate in their dangers, their wants, their joys, their sorrows. Only in this way can they estimate battle worth and the requirements of the troops.

Man is not responsible for himself alone, but also for his comrades. He who can do more, who has a greater capacity of accomplishment must instruct the inexperienced and weaker ones.

From such conduct the feeling of real comradeship develops, which is just as important between the leaders and the men as between the men themselves.

13. Troops only superficially (and not through long training and experience) welded together, more easily fail under severe conditions and under unexpected crises.

Therefore, before the outbreak of war, the development and maintenance of steadiness and discipline in the troops, as well as their training, is of decisive importance.

Every commander is enjoined immediately to intervene with all power at his disposal against any relaxation of discipline, against excesses, plundering, panic and other damaging influences.

Discipline is fundamental in an army, its strict maintenance a benefit to all.

14. The strength of the troops must stand in proportion to the objective desired. Unrealizable demands prejudice the trust in leaders and shake the spirit of the troops.

15. From the youngest soldier on up, the employment of every spiritual and bodily power is demanded to the utmost. Only in such conduct is the full power of accomplishment of the troops achieved.

Thus do men develop and maintain their courage and powers of decision in hours of stress and carry forward with them to greater deeds their weaker comrades.

The first demand in war is decisive action. Everyone, the highest commander and the most junior soldier, must be aware that omissions and neglect incriminate him more severely than the mistake of choice of means.

Published in 1933, Truppenführung served as the “keystone manual” of the German Army for twelve years. The text of this article comes from a translation made at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College in 1936. The footnotes are my own.

The term translated as “scientific” [Wissenschaftlich] referred to knowledge gained from deliberate study. It was therefore free from much of the baggage born by its present-day descendent.

The word here translated as “personality” [Persönlichkeit] might be better rendered as “whole man.”

The “emptiness of the battlefield” [die Leere des Schlachtfeldes] is a phrase made popular by Wilhelm von Scherff (1834-1911), a veteran of the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) who wrote extensively about his experience of open-order fighting in that conflict.

This I have and read

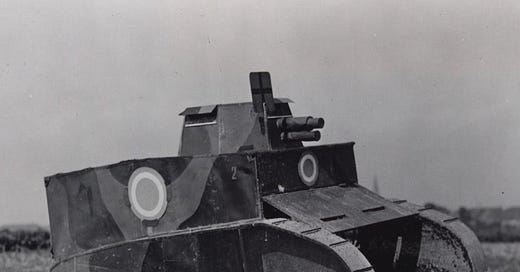

Sorry to be looking at older items, but I was just looking at the picture.

It is obviously a care pretending to be a tank.

I recognized that before.

What I did not think about was that it looks very much like a FT. That and the roundel says "we are pretending to be French" ?

Which Lehr unit would this be?