The estate of the late John Sayen has graciously given the Tactical Notebook permission to serialize his study of the organizational evolution of American infantry battalions. The author’s preface, as well as previously posted parts of this book may be found via the following links:

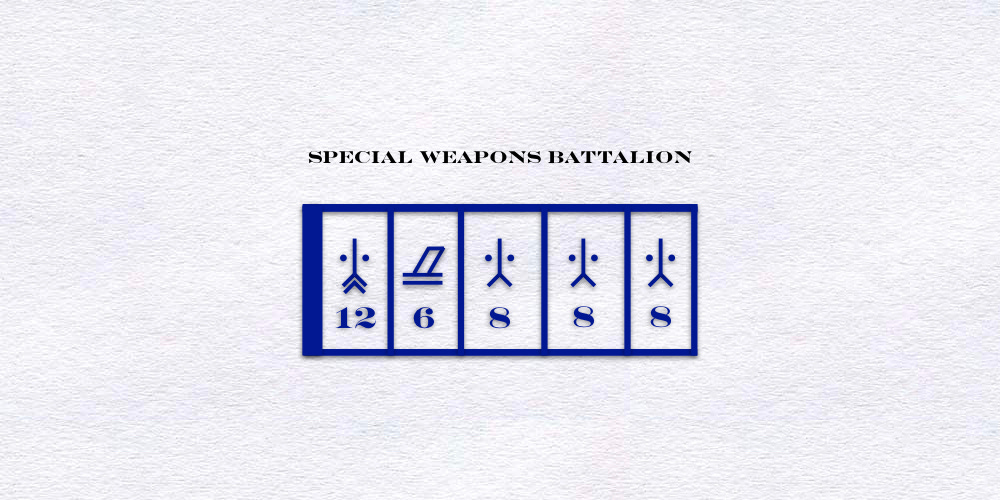

In 1935, the Army incorporated its new ideas in another testbed infantry regiment (see Appendix 4.1) that would exercise both motorization and the new weapons. As usual the 29th Infantry Regiment at Fort Benning served as the “guinea pig” for the new organization, which involved a complete redistribution of its crew-served weapons. Its three infantry battalions became “rifle” battalions and retained only their rifle companies. Their machine gun companies, cut down to only two platoons apiece, became the nucleus of a new “special weapons” battalion. This battalion also received an antitank company with three platoons of .50-caliber machine guns and a mortar company with three platoons of the new Hotchkiss-Brandt 81mm mortars.

Each rifle or weapons battalion operated under a small staff supported by a headquarters detachment rather than a headquarters company. The detachment provided only command personnel and a message center. Most communication personnel came from a communication platoon (of 5 officers and 116 men) in the regimental headquarters company. This unit supplied a section of wire and radiomen and a communication officer to the regimental headquarters and each battalion headquarters. The three rifle battalions remained almost entirely on foot (even their attached communication sections were each allowed only a single 1.5-ton truck) but the rest of the regiment was fully motorized.

It was hoped that collating all the regiment’s heavy weapons into a fourth battalion would give the regimental commander a large and very flexible firepower reserve. Although each .30 caliber machine gun company could be attached to an infantry battalion, it was considered doctrinally desirable that the fire of these guns be massed as much as possible. Thus a battalion that was to conduct a major attack might have two or even all three machine gun companies firing in its support. On the other hand, the primary purpose of the .50-caliber antitank company was to provide guns for antitank protection.

Thus, rather than being concentrated, the .50-caliber machine guns were to be dispersed throughout the regiment’s sector, thereby covering all possible routes that enemy tanks might take. Since most of the world’s tanks in 1936 were in fact very lightly armored, the use of a .50-caliber gun as an antitank weapon was not unrealistic, although spreading the guns out probably was. The .30 caliber machine guns were also intended to provide air defense.

Field-testing soon revealed that the Fourth Battalion commander could exercise few tactical responsibilities. In practice his three machine gun companies nearly always operated under the three rifle battalion commanders while his antitank and mortar companies worked directly under the regimental commander. Therefore the Fourth Battalion commander generally acted as an advisor to the regimental commander on the best use of his weapons, while he ensured that his forward-deployed companies remained fully stocked with ammunition.1

Since 1921, the 29th Infantry Regiment had been without its third battalion. Not only was a third battalion not created under the test organization, but the fourth battalion’s third machine gun company that would have supported it was not created either. Likewise, the headquarters company did not maintain communication or truck sections for a third battalion. A third truck section was later created, however, as experience showed that some trucks were needed to simulate the third battalion’s presence during maneuvers. Later, the regimental headquarters company also improvised a headquarters detachment for the missing battalion. Throughout its brief life span the test regiment carried out extensive maneuvers in which it operated both on its own and with light tanks and motorized artillery.2

By December 1936, enough experience had been gained for a further refinement of the new regiment. Within the rifle platoons, the rifle sections were eliminated and replaced by three nine-man rifle squads and an eight-man LMG squad operating three BAR/LMGs. A lieutenant, two sergeants (a platoon sergeant and assistant), and three messengers made up platoon headquarters. A five-man light mortar squad carrying an experimental Hotchkiss-Brandt 47mm mortar reinforced each rifle company headquarters. The 47mm mortar was a scaled down 81mm that could fire exploding shells or pyrotechnics for signaling.

Rifle company strength fell to five officers and 137 men. A rifle battalion would employ three of these reduced rifle companies in peacetime but would get a fourth one in war. At the same time, the Infantry Board reconfigured the special weapons battalion. It eliminated the mortar and antitank companies but added a .50-caliber antitank machine gun platoon to each machine gun company and moved the 81mm mortars to the division artillery. These changes cut the total wartime strength of the reorganized regiment to 110 officers and 2,362 men (excluding attached medical personnel and chaplains).3

Testing in 1937 and 1939 was even more exhaustive and embraced not just the 29th Infantry but the entire 2nd Infantry Division, now structured as an experimental division for the tests. Field trials were supplemented by General Staff studies that not only plumbed previous maneuvers but also promulgated the recommendations of many senior officers and knowledgeable individuals together with the results of an extensive study of foreign division organizations. The findings of these studies finally settled the old post-World War I arguments about the merits of “square” or “triangular” infantry division decisively in favor of the latter. However, square divisions still endured (at least in the National Guard) until wartime mobilization began in earnest at the end of 1941.4

The chief of staff of the experimental 2nd Division was Colonel Leslie J. McNair, an officer whose experience in designing tactical organizations stretched back to the First World War. McNair’s influence on the test exercises was profound and he saw to it that they were as thorough and realistic as technology and peacetime budgetary constraints permitted. He was able to assemble and evaluate an entire division organization piece-by-piece, beginning with the rifle squads.

Testing focused on such issues as frontages that given units could or should hold; firepower per man and per unit; ammunition allowances; and the impact of motorization on mobility in general and on transportation capacities in particular. It also looked at what the infantry needed in terms of artillery support and also devised a methodology for echeloning automatic rifles, machine guns, and mortars within the infantry regiment. Other issues such as maintenance requirements; time/distance studies; communications; what service support elements the division had to have, and what service support functions could be relegated to corps and army echelons were also examined.

McNair summarized his findings in a report first published in March 1938 wherein he recommended the adoption of a very austere triangular infantry division of 10,275, with three infantry regiments of about 2,400 each. McNair got rid of the weapons battalions and restored the infantry battalion as the basic fighting element. He believed that regiments should no longer be the fighting units because firepower improvements were distributing them over frontages too broad for easy control. Battalions should subsume all combat and combat support elements required in most combat situations. Less critical elements could be attached when needed.

The infantry battalions regained their machine gun companies but those companies lost their .50-caliber antitank platoons. The 81mm mortars, having been found unsuitable for the artillery, reappeared in a two-gun platoon in each infantry battalion headquarters detachment. This increased the latter’s strength to five officers and 63 men.

The number of 47mm mortar squads increased from one per company to one per platoon. The elimination of ammunition bearers reduced each mortar squad to two men but platoon messengers or anyone else who might be available could help carry mortar ammunition. These changes boosted each rifle company to five officers and 168 men.

An important consideration underlying this increase was that small rifle companies were less economical with manpower. Even a smaller company needed almost same number of rear echelon personnel (mess and supply sergeants, clerk, cooks, etc.) to support itself as a much larger one did. Thus, replacing four small companies with three larger ones saved a company’s worth of “overhead” while offering comparable firepower and mobility.

At the regimental level, antitank defense was concentrated into an antitank company of eight of the new M3 37mm guns. These guns were American produced versions of the German 3.7cm PAK 35/36. They not only replaced .50-caliber machine guns in the antitank role but their ability to fire high explosive shells also enabled them to replace the old M1916, M1, and M2 37mm guns in the infantry support role. The regimental service company was broken up, its elements being absorbed by the battalion headquarters detachments and the regimental headquarters company.5

Editor’s Note: The format of the many appendices to this work fit poorly with Substack. For that reason, I have placed them on a PDF file that can be found at Military Learning Library, a website that I maintain.

“Infantry Digest - The Infantry Regiment-New Style” Infantry Journal January 1936, pages 69-70; Lieutenant Colonel T. J. Camp “The Fourth Battalion” Infantry Journal May-June 1936, page 201; see also The Infantry School “The New Infantry Regiment” and “Tactical Aspects of the Proposed New Regiment” The Infantry School Mailing List Volume XI January 1936, page 1-52.

Lieutenant Colonel Vernon G. Oldsmith “Tanks, Trucks, Troops” Infantry Journal September 1936, pages 402-407

Virgil Ney, The Evolution of the U. S. Army Infantry Division, 1939-1968 (Fort Belvoir VA: Combat Operations Research Group, 1969) pages 110-111; and The Infantry School, “The Rifle Platoon in Foreign Armies” The Infantry School Mailing List Vol XV 1938, pages 181-193

Ken Roberts Greenfield, Robert R. Palmer and Bell I. Wiley The Army Ground Forces: The Organization of Ground Combat Troops (Washington DC: Historical Division, 1947) pages 271-275

Lieutenant Colonel Harry C. Ingles “The New Division” Infantry Journal November 1939, pages 521-529