On 8 February 1945, the British XXX Corps initiated an attack “with limited objectives” aimed at the capture of a piece of ground along the border between the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the German Reich. The plan for this operation, which had been given the codename of Veritable, called for the progressive destruction, over the course of two days, of the three lines of resistance that German forces had built along the western edge of this feature.

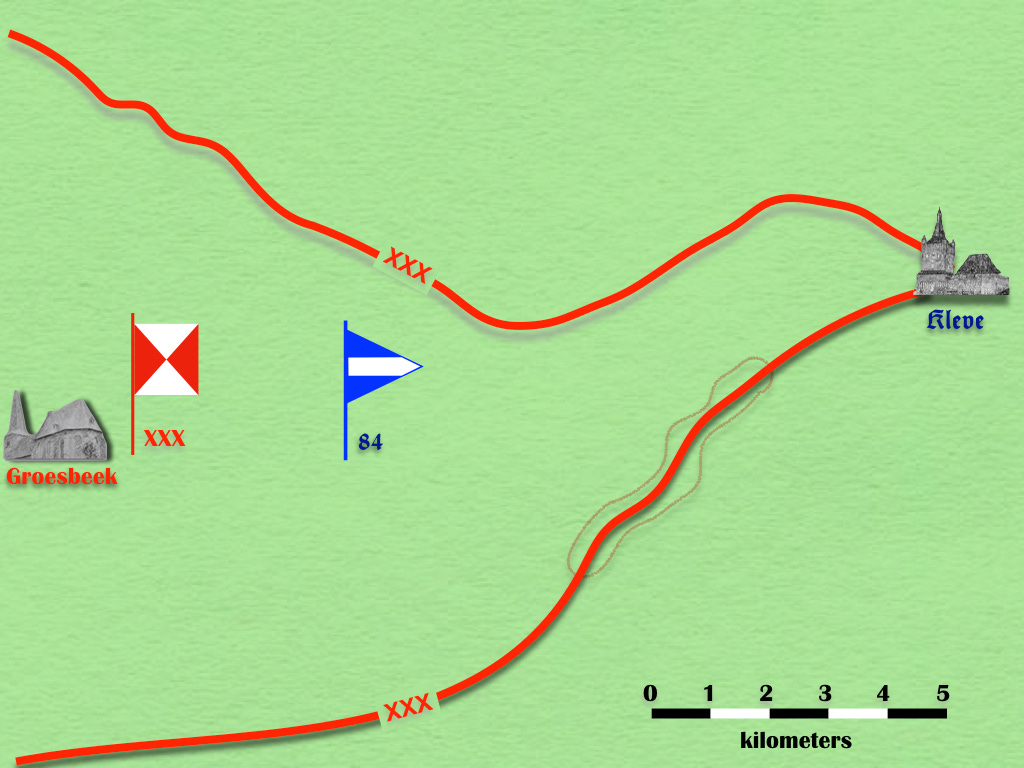

Depicted on a map, the area to be taken resembled a horn-of-plenty. (The bell of the cornucopia came close to embracing the Dutch town of Groesbeek. The point pointed to the German town of Kleve. The north edge of horn ran along the highway ran west out of Kleve. The south side coincided, in part, with a low but well-wooded ridge.)

According to Lieutenant General Brian Horrocks, the general officer commanding XXX Corps, the scheme for capturing this oddly-shaped piece of ground left “no room for maneuver and no scope for cleverness.”1

On the first day of Veritable, Anglo-Canadian units bombarded the German defenses with field pieces, guns and howitzers of heavier sorts, mortars, anti-aircraft guns, 5-inch rockets, anti-aircraft guns, anti-tank guns, machine guns, and the main armament of tanks. In doing so, they consumed some 5,953 tons of ammunition.2

Fewer than 3% of the German defenders of the bombarded areas were killed or wounded by this “storm of steel.” Nonetheless, the effect was such that the Anglo-Canadian forces were able to take their objectives without significant resistance. Indeed, the author of the official history of the Royal Artillery in the Second World War noted that “the principal difficulties encountered during the first two days’ fighting had been mud, mines, and flooding.”3

Given the light German casualties, it is reasonable to conclude that the chief impact of the Anglo-Canadian bombardment was not physical but moral. The Germans were not blasted into “smithereens.” Rather, they were blasted into such a state of mind that they preferred surrender to continued resistance.

This is confirmed by the testimony that the German defenders gave to their captors after surrendering. The first effect of the bombardment, they agreed, served to give the impression that the Allies were part of an irresistible force against which resistance was futile.

The second effect of the bombardment was to deprive the German units of their cohesion. Sheltering in small groups in bunkers and shelters, the German soldiers lost contact with other groups. Runners could not get messages through. Officers and senior non-commissioned officers could not make their rounds.

Had the German formation bombarded in the course of Veritable, the 84th Infantry Division, been composed of well-trained men of fighting age led by dynamic squad and platoon leaders, it is quite possible that it would have retained its fighting power. Other German formations had, in the course of both world wars, suffered comparable bombardments, often for longer periods of time, and had still “come out swinging.” However, the 84th Infantry Division, which had been characterized by British intelligence as “a formation of low category and rather elderly men,” was not such a formation.

Veritable was but one of the many attacks in which the British observed that the principle effect of heavy artillery bombardments was moral rather than physical. At the end of European campaign, an anonymous British author penned the following analysis of what could and could not be expected from such bombardments.

It is generally realized that against an enemy in a prepared position, the casualties likely to be caused by any practicable weight of preliminary artillery fire will seldom be cripplingly high. The subsequent difficulty of assaulting the position is likely to be affected by the moral effects of the preliminary bombardment than by the physical casualties it causes.

Unfortunately, the moral effect of a bombardment largely depends on factors which are beyond the gunner’s control and often unknown to him. Thus the quality of the opposing troops and their mental and physical conditions will go far to decide whether they are or are not badly demoralized by a given bombardment. Again, the demoralizing effect of a given bombardment often wear off very rapidly after it ceases.

Ten minutes’ delay in reaching the objective on the part of the infantry may mean the difference between practically no opposition and vigorous defense. It follows that any quantitative statement of the amount of fire needed to bring about demoralization must be regarded as a very broad approximation indeed. The most that can be said is that bombardment of certain intensities and duration have been associated with success in the past. Whether they would still be successful in different circumstances is by no means certain.

In particular it must be remembered that ability to endure bombardment may be associated with racial characteristics, and that what is true of the German soldier is not necessarily true of the Japanese.

With these reservations there are, however, certain principles which appear from the available evidence to be of fairly general application to the fighting in Europe:

1. Genuine demoralization by artillery fire is comparatively rare, and must not be confused with the ‘neutralization’ of enemy fire produced by an ordinary barrage. A barrage, properly used, will usually ‘keep the enemy’s heads down’, and thus enable the infantry to close the objective. But it will seldom break the enemy’s will to fight, and unless the infantry are ‘leaning on the barrage’ they are liable to encounter a defense with its morale little affected. Genuine demoralization only occurs when the bombardment has been so severe that for some useful period of time after it has ceased, the enemy is unable to regain his will to fight.

2. Even when the enemy has been not only neutralized during the bombardment, but remains demoralized after it, the period of maximum demoralization is usually short. Recovery is going on all the time, and with troops of normal quality, the period in which resistance will be negligible can usefully be reckoned in minutes. Speed of follow-up is essential if full advantage is to be taken of the moral effect of the bombardment.

3. There is some evidence that the degree of demoralization produced is related both to the weight and duration of the bombardment. The most successful bombardments in breaking morale appear to be those which combined a certain minimum intensity with a certain minimum duration. It is believed (though this cannot at present be proved) that increased weight is no substitute for the necessary minimum duration and that increased duration is no substitute for the necessary minimum weight.

4. For the reasons given above, no definite statement of the necessary minimum weight and minimum time can be given. But it may be noted that few, if any, bombardments of much less than three hours in duration, or of much less than 0.3 pounds per square yard in weight over the area attacked, appear to have produced notable collapses of enemy morale.

5. The above figures are given merely to indicate the order of weight and duration which, in the past, has been associated with definite breakdowns in morale. It must be clearly realized:

a. that the employment of a bombardment of this weight and duration is certainly no guarantee that enemy morale, in any given instance, will be broken and -

b. that successful attacks have of- ten been made with far less preparation, even though the enemy ’s will to fight does not seem to have been greatly affected. A significant breakdown of enemy morale is a desirable, but not an essential, feature of a successful attack.

6. From the point of view of a typical practical situation, thereof in which a limited fire-power has to be employed to the best advantage against troops of average quality in ordinary field defenses, such evidence as is available suggests the following broad tactical principles as applying to European troops:

a. Unless sufficient guns and ammunition and time are available to enable a total weight of preparatory bombardment of about 0.3 pounds per square yard to be delivered over about three hours, a major breakdown of enemy morale will probably be very difficult to bring about. Shorter or lighter preparatory bombardment than this may still be valuable in preventing enemy movement and cutting communications. But it is wise not to plan on the assumption that they will have greatly reduced the enemy’s will to fight.

b. In those circumstances therefore the first call upon the available resources should be for thorough neutralization of the enemy defenses during the advance. Don’t skimp the neutralizing fire in order to indulge in speculative softening up.

c. If sufficient guns, ammunition, and time are available to deliver about 0.3 pounds per square yard over a period of about three hours, then a considerable reduction of the enemy ’s will to fight may occur though it is still by no means certain to do so.

d. On the whole, better results are likely to be obtained by putting down this minimum weight of shell over the whole period of three hours, than by crowding a similar weight into a shorter and more intense bombardment.

e. Once the bombardment has started, the aim should be to produce continuous strain, without long pauses, and with a crescendo of intensity just before the attack is delivered.

f. Whatever degree of softening effort has been made, speed of follow-up is all-important. Except in very rare circumstances where intense bombardment can be maintained for days, the likely duration of the effective breakdown of enemy morale will be very short. With bombardments of the minimum time and intensity given above, the infantry must be able to be on their objective in something of the order of five minutes after our own fire lifts. If the nature of the ground means a delay of twenty minutes or half an hour, it is very questionable whether success through ‘softening’ will be ‘on’ with this weight and duration of bombardment.

g. In all instances where resources are anywhere near the minimum suggested above, therefore, it is wise to regard the breakdown of enemy morale as a bonus which may be achieved, but not to rely purely or mainly upon it for the success of the attack.

h. In particular, if there is any doubt about the ability of the shell to defeat the defences, e.g. if any considerable proportion of the defenders are in positions not vulnerable to a direct hit, the whole situation changes. It must be realized that ineffective ‘softening’ fire may not only be a waste of ammunition, but may positively encourage the enemy.4

A. L. Pemberton, The Development of Artillery Tactics and Equipment (London: The War Office, 1950), page 263

Shelford Bidwell and Dominick Graham, Firepower: British Army Weapons and Theories of War, 1904-1945 (Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2004), page 290.

Pemberton, The Development of Artillery Tactics and Equipment, page 267

United Kingdom Artillery Notes 19, U.S. National Archives, Record Group 337, Entry 47, Box 93, Folder 319.1 (U.K. Artillery Notes)