Welcome to the Tactical Notebook, where you will find more than four hundred tales of armies that are, armies that were, and armies that might have been. If you like what you see here, please share this article with your friends.

In April of 2023, French historian Michel Goya published a description of the Russian defenses in Zaporizhzhia that brought to mind the field fortifications built by Soviet forces prior to the battle of Kursk. Like the Soviet positions of 1943, the Russian defenses in Zaporizhzhia make extensive use of minefields, dug-in armored vehicles, successive lines of defense, and a powerful counterattack force.

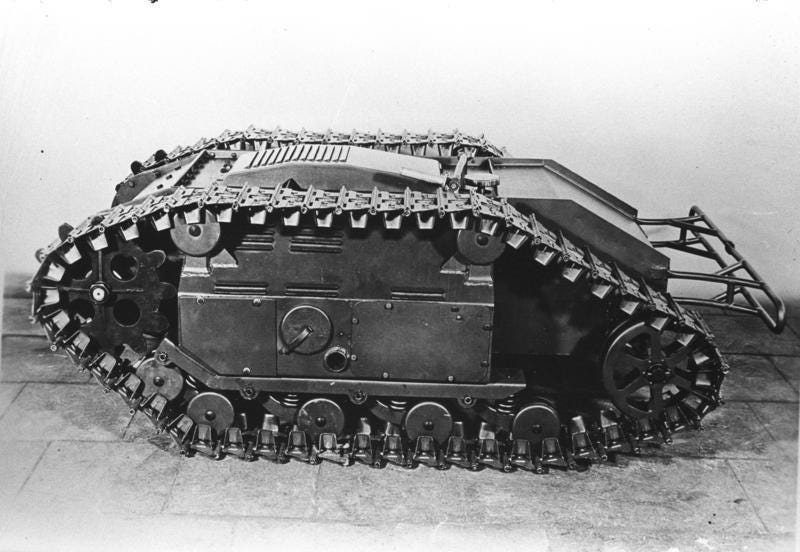

Recent Ukrainian attacks in Zaporizhzhia, however, bear little resemblance to the operations conducted by German forces at Kursk. On the first day of their offensive (5 July 1943), the Germans took great pains to clear broad paths through Soviet minefields. (In some cases, this involved the use of Sprengpanzer, remotely-controlled tracked vehicles packed with explosives. In others, engineers removed mines by hand.) In Zaporizhzhia, however, the chief means of mine clearance seems to have been tanks fitted with plows.

While the mine plows did a good job of dealing with mines that would otherwise have exploded under the tanks pushing them, the lanes that they cut in mine fields were long and narrow. Moreover, as few Ukrainian tanks were fitted with such devices, the total number of lanes made seems to have been painfully small.

It did not take the Russians long to figure out that the critical vulnerability of column of armored vehicles advancing along a narrow lane was the mine plow tank leading the way. Immobilizing that tank, after all, would place the commanders of the following vehicles on the horns of a dilemma. If they stopped moving, they became vulnerable to the fire of the artillery pieces, multiple rocket launchers, and dug-in museum pieces covering the minefield. If, however, they played the impatient motorist, and tried to move around the mine plow tank, they would soon run afoul of uncleared mines.

The high cost of doing things this way raises the question of the absence of the sort of mine clearing devices that have been available to armies for the past eighty years: munitions filled with fuel-air explosives, rocket-delivered line charges, and the descendants of the Sprengpanzer. Similarly, in a war in which drones of various sorts abound, the Ukrainian forces should have been provided with the terrestrial equivalents of the aquatic robots employed against Russian ships in the Black Sea.

This “dog that failed to bark” leads me to think that the Ukrainian program of attacks in Zaporizhzhia has a lot in common with the Anglo-Canadian landing at Dieppe in August of 1942. In sharp contrast to Operation Citadel, which was aimed at the destruction of Soviet forces in the Kursk Salient, the “raid” at Dieppe had no operational objective. Rather, it served two political purposes: convincing Americans of the inherent difficulties of an amphibious assault on the coast of France and proving to the Soviets that the British Empire was willing to make otherwise senseless sacrifices for the sake of the Grand Alliance.

<em>the Anglo-Canadian landing at Dieppe in August of 1942. ... had no operational objective.</em>

The author David O'Keefe (<em>One Day in August</em>) would disagree sharply with this assessment. Based on documents being declassified since the war, he makes a strong case that Operation Jubilee was mounted as <strong>cover</strong> for an intended "pinch" raid to capture updated Enigma machines and associated encryption materials (this was just after the Germans had introduced the four-rotor Enigma, which disrupted Bletchly Park's ability to decipher German naval traffic). A small raid, whether successful or not, would let the Germans know that the British were actively trying to get their hands on the new machine and paraphernalia, but a big "invasion rehearsal" where there was a lot of damage might (and O'Keefe believes, <em>did</em>) confuse the situation enough to hide the real reason for the operation.

In the event, Operation Jubilee was a cluster on so many levels, including the crucial "pinch" team's ship being hit and seriously damaged while still offshore, that nobody came out of the day with reputation intact ...

Here's a Toronto Star review of the book (which I believe has been updated with a second edition) - https://www.thestar.com/entertainment/books/2013/11/05/one_day_in_august_by_david_okeefe_review.html

The YouTube channel D-Day 24 Hours had an interview with O'Keefe in this episode (beginning at about the 17:30 timestamp) - https://youtu.be/k_uleFxJ1MM

Considering how many specialized pieces of equipment an army needs to fight, and how different the requirements can be between mission types, I wouldn't be surprised if there were simply very few mine clearers in general. Before February 2022, "attack through a defended minefield covered by fire", was probably not a requirement on most people's minds, probably even the professionals.

Because equipment is so specialized now, more and more, you go to war with what you have rather than with what you want or can make.