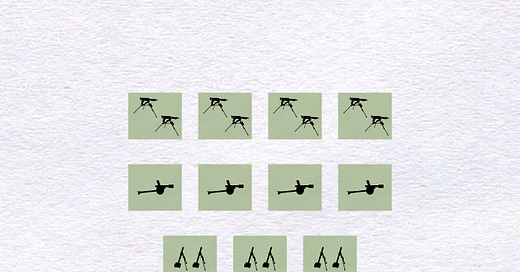

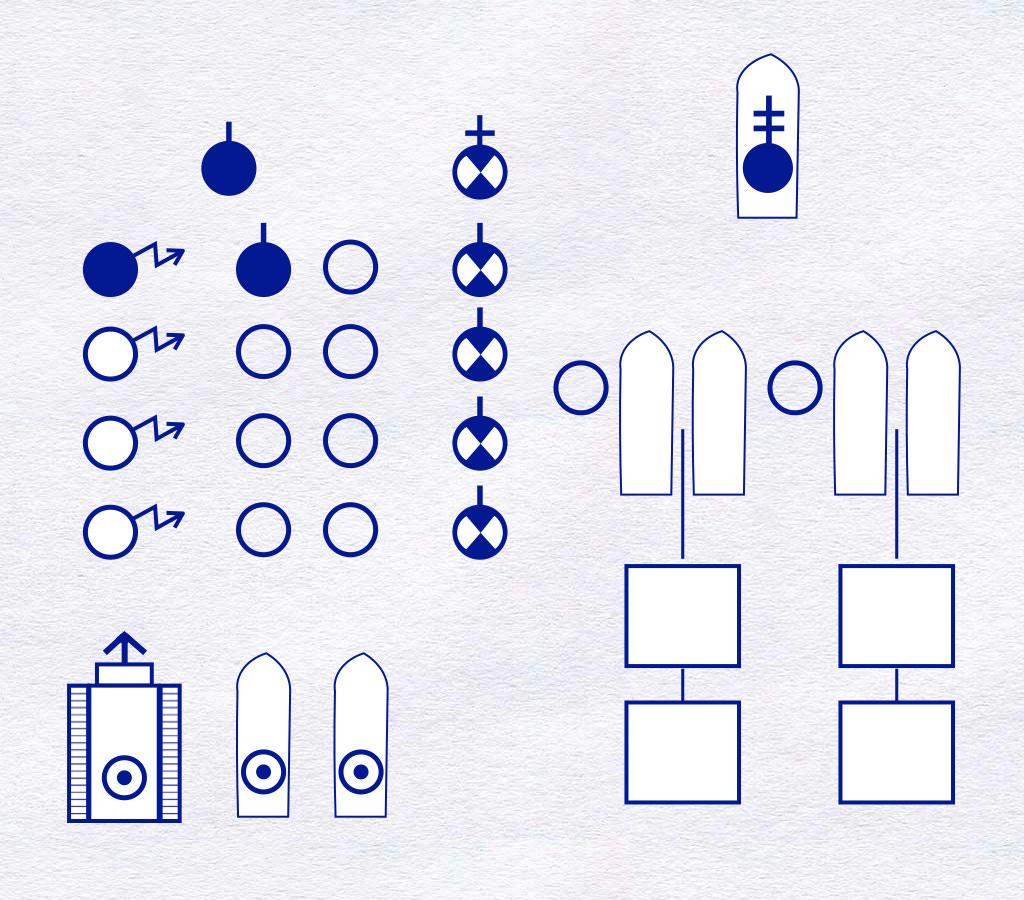

The heavy (Schwere) company of a Grenadier battalion of a Volksgrenadier Division of the 32nd Mobilization Wave consisted of a headquarters and four fighting platoons. Of the latter, the first two wielded heavy machine guns, the third 75mm infantry guns, and the fourth 81mm mortars.

Though it might also be employed as a pool of platoons, the heavy company often operated as a single element. In cases where the battalion commander designated a main effort (Schwerpunkt), it focused its own fires in ways that assisted that element. If a concentration of fires of that sort made no sense, the heavy company could establish a framework of long range fires that facilitated the shorter-range work of the Grenadier companies.

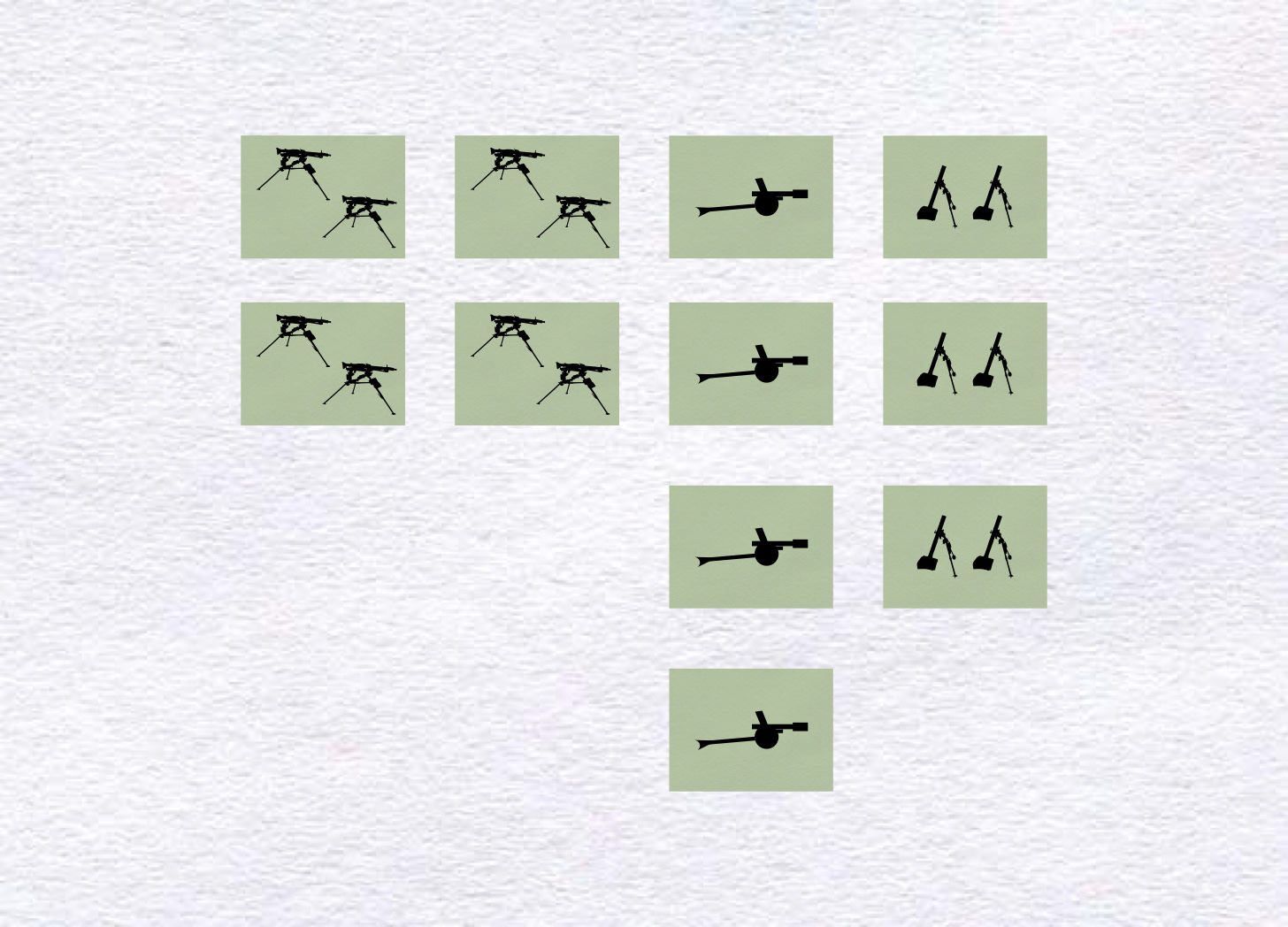

These roles differed little from those played by the heavy companies of the early years of the war. Indeed, the difference between the heavy company of the Volksgrenadier battalion and its predecessors lay largely in the realm of communications. In particular, the new unit made use of a greater number of portable radio sets and a hybrid vehicle, called the Kettenrad, that might well be described “half-track motorcycle.”

In keeping with this emphasis on communications, most of the men assigned to the headquarters of the heavy company served as signallers of some sort. Seven laid telephone wire, four turned the dials on radio sets, and three delivered messages by hand. (Two of the messengers rode horses. One drove a Kettenrad.)

The squads made up of radio operators and wiremen rated leaders who ranked as sergeants. All of the messengers, however, ranked as ordinary soldiers. Because of this, I suspect that they reported directly to the leader of the headquarters section (Kompanietruppführer). Moreover, as the tables of organization for this company make no provision for a ‘communications chief’, I wonder if the Kompanietruppführer played that role as well.

A group composed of a first sergeant (Hauptfeldwebel) and four specialized sergeants (Unteroffiziere) supervised the interior economy of the company. Thus, the first sergeant harmonized the whole, the Gerätunteroffizier supervised the care of equipment, the Rechnungsführer accounted for pay and supplies, the Sanitätsunteroffizer managed medical care, and the Waffenmeister repaired broken weapons. (All five of these ‘admin and logistics’ non-commissioned officers rode bicycles.)

Source: General der Infanterie beim Chef Generalstabs des Heeres, Nr. 3160/ 44g vom 5.9.44, microfilmed at the U.S. National Archives, Captured German Records , Series T-78, Reel 763. (The link will take you to a PDF of this document on file at the Military Learning Library.)

For a guide to the symbols used in the second diagram:

For further reading:

To share, support, or subscribe: