The workhorse of the German artillery of the First World War was not, as one might expect, the counterpart to the British 18-pounder or the celebrated “French 75.” Rather, it was the various versions of the heavy field howitzer, the 150mm pieces that fired the forty-three kilogram shells that French soldiers called marmites (“big soup kettles.”)

At the start of the war, the most recent incarnations of the schwere Feldhaubitze could be found in the battalion of sixteen such weapons assigned to each active army corps. Older versions, which fired the same sort of projectiles, could be found in fortresses, siege trains, and arsenals.

With the onset of trench warfare, the older weapons migrated to the front. Thus, by the first anniversary of the outbreak of the war, there were nine heavy field howitzers for every infantry division serving at the front. Moreover, as new pieces of that persuasion were emerging from workshops each week, it would not be long before that ratio increased.

This embarrassment of riches raised the question of where, in the organizational structure of the German armies, to put the heavy field howitzers. The most obvious solution would have been the extension to all formations, whether Reserve, Ersatz, Landwehr, or wartime, of the arrangement employed by active army corps. That is, for each two-division army corps, the war ministries of the German Empire would form a four-battery battalion of heavy field howitzers. (Independent divisions and the third divisions of three-division army corps would get two-battery half-battalions.)

In the view of Ludwig von Lauter, the inspector of the heavy artillery branch [Fußartillerie] of the Prussian Army, this obvious solution ran afoul of two problems. The first was his belief that the ideal allocation of heavy field howitzers to army corps was not four batteries, but six. The second was the need to provide a home to the heavy pieces that had proved themselves worthy hand maidens of the heavy field howitzer: the 210mm howitzers that German gunners called “mortars” [Mörser], heavy guns of the lighter sort (with calibers of 100mm or so) and heavy guns of the heavier sort (with calibers between 130mm and 150mm).

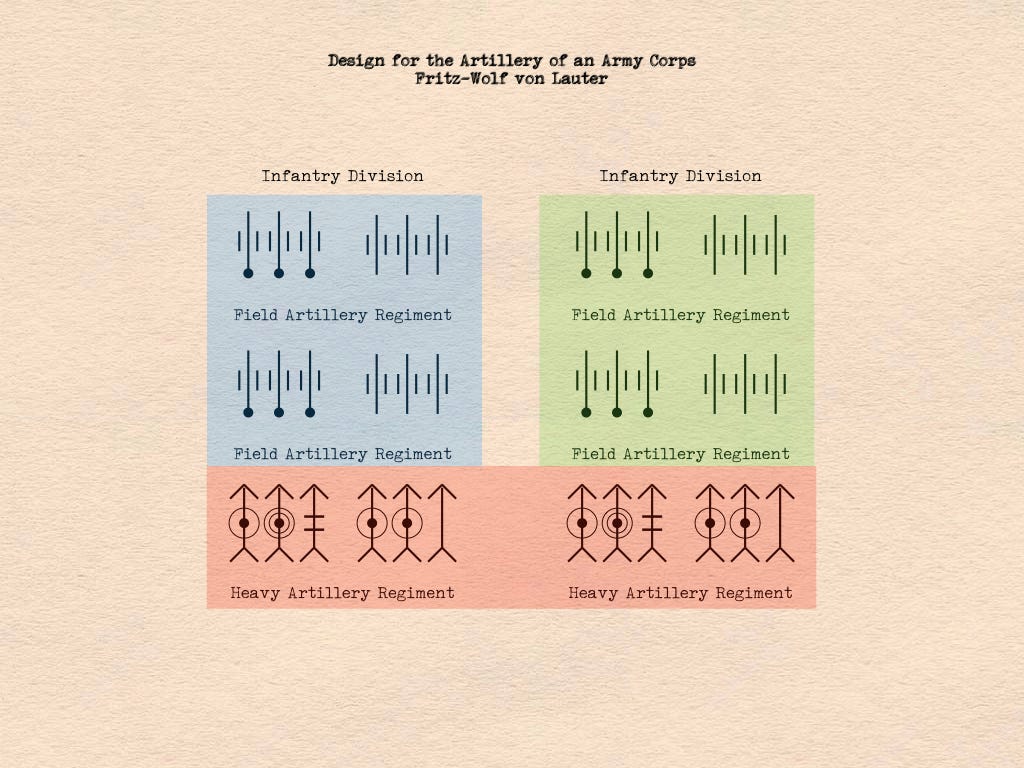

General von Lauter therefore proposed the organization of a heavy artillery brigade for each army corps. This brigade would consist of two mirror-image regiments, each of which would be affiliated with one of the divisions of the army corps. Each regiment, in turn, would consist of two battalions. The heavier of each pair of battalions would consist of a battery of heavy field howitzers, a battery of 210mm howitzers, and a battery of “heavier” heavy guns. The lighter battalion of each regiment would comprise two batteries of heavy field howitzers and a battery of 100mm heavy guns.

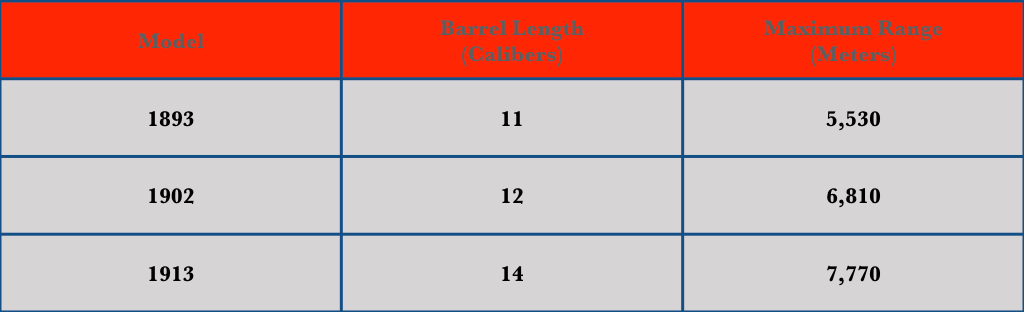

In the 32-page memorandum proposing this scheme, von Lauter makes no mention of specific models of heavy field howitzer. We can be sure, however, that he was aware that new models of such weapons were provided with longer barrels than older ones, and were thus capable of firing upon more distant targets. It is thus reasonable to assume that the battery of heavy field howitzers assigned to the “heavier” of the two battalions of each regiment would have been equipped with the newest models available at the time.1

Although von Lauter’s proposal deals chiefly with heavy artillery, one of its most interesting features is the presumption that half of the batteries of the field artillery regiments of infantry divisions would be armed with 105mm light field howitzers. This ratio of light field howitzers to field guns would not be achieved during the war. Indeed, as many of the German divisions that took the field in 1914 did so without any light field howitzers at all, it would take two years for all German infantry divisions to obtain a battery of light field howitzers for every two batteries of light field guns.

As might be deduced from the sub-title of this post, von Lauter failed to obtain the high-level support needed to implement his scheme. Thus, while the German armies eventually succeeded forming many of the independent heavy batteries formed in the 1914 and 1915 into battalions, there was no program to form those batteries into regiments, let alone brigades. Nonetheless, the structure that von Lauter chose for the lighter battalion in each of his heavy artillery regiments - one battery of 100mm heavy guns and two batteries of heavy field howitzers - became the model for the single heavy artillery battalion possessed by most German infantry divisions of 1918, as well as many that served in the Second World War.

Source: Ludwig von Lauter, Beitrag zur Frage der Organisation der Artillerie, PH 9-II/1, Bundesarchiv.

The figures given in the chart come from Herbert Jäger, German Artillery of World War I (Ramsbury: Croward Press, 2001), table on page 34.