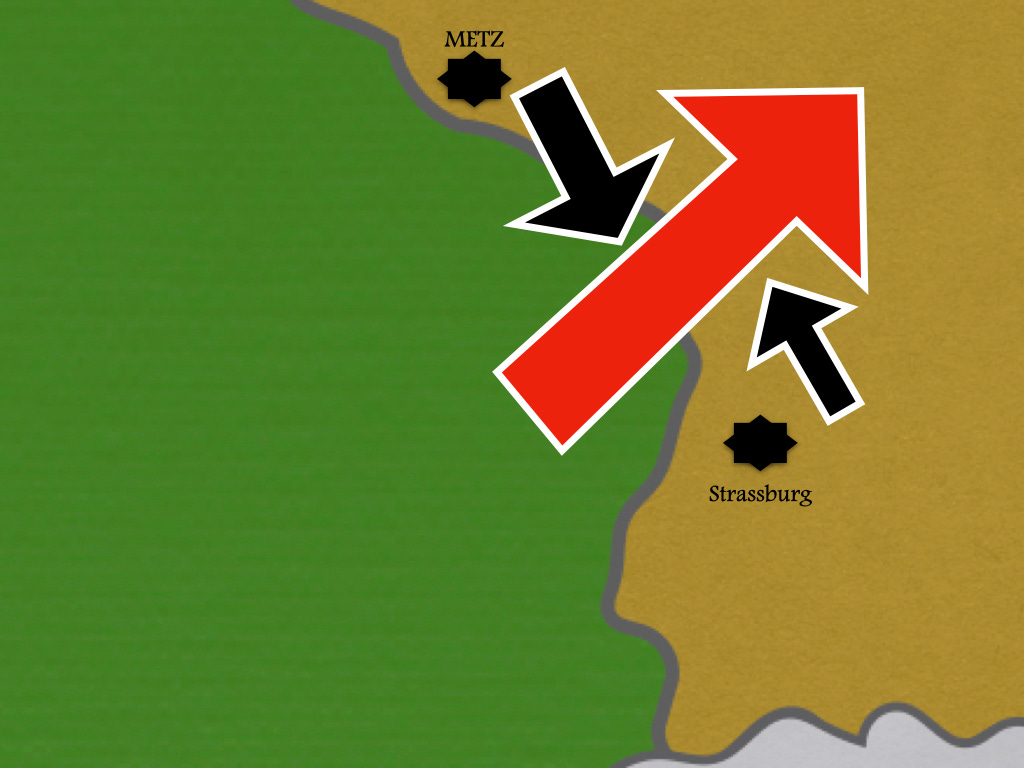

In Deployment on Two Fronts, Hermann Staabs imagined a scenario in which the German forces mobilized in August of 1914 were divided evenly between the fight against Russia and the struggle against France. In such a situation, the German forces in the west would begin the war in a defensive posture. To be more precise, while eleven of the nineteen army corps took up defensive positions on the Franco-German frontier and one guarded the border with Belgium, seven would be kept in reserve.

If the French attacked with all twenty-one of their army corps, the balance of forces would have been more or less even. That said, the Germans enjoyed several important advantages. First, they would be defending familiar ground against an enemy that was poorly provided with heavy field howitzers. Second, the geometry of the frontier made it easy for the Germans to attack the flanks of attacking French forces. Indeed, the further the French advanced, the more vulnerable they would become. Third, the Germans possessed a pair of fortresses that, in addition to providing a variety of other services, would protect the German forces gathering on each side of the French penetration.

Two powerful considerations would have impelled the French leadership to launch a large-scale attack into German territory. First, agreements made with the Russia before the war obliged France to go on the offensive at the start of a two-front war against Germany. Second, just about anyone who had any influence in France in 1914 desired the liberation of the territories on the German side of the border, the lost provinces of Alsace and Lorraine.

Under these circumstances, it is hard to imagine a successful outcome for France. If the French forces failed to breakthrough the German trenches, the result would be stalemate. If they managed to tear, and exploit, a hole in the German defenses, then they would find themselves deep in enemy territory, surrounded by the many second- and third-line units raised at the start of the war.

What is possible to imagine is an early outbreak of the sort of “collective indiscipline” that, in the real world, took place in the spring of 1917. In the absence of a German invasion of France, there would have been no “sacred union” [union sacrée] uniting Catholic and Republican, town and country, worker and bourgeois, Languedoc and Langue d'oïl. Likewise, there would have been no chance of a “miracle of the Marne” to redeem the reputations of the military leadership and foster faith in eventual victory.

In the aftermath of their initial defeats, each member of the Franco-Russian alliance would call upon its partner to redouble its efforts. In the west, where soldiers talked politics around the campfire and could read propaganda leaflets dropped from aeroplanes, this would lead easily to the belief that poilus falling victim to Mausers and Maxim guns were dying, not for France, but for Russia.

In the situation described by Staabs, France would also suffer from the absence of the services that, in the real world, had been provided by the British Empire. A France that had not been invaded by seven German field armies would have needed little in the way of British coal or British steel. Without the help of Great Britain, however, it would have been hard pressed to keep Italy neutral, prevent German landing forces from descending on its smaller colonies, or obtain loans from banks in the United States.

For Links to the Other Posts in This Series:

To Share, Subscribe, or Support: