The End of History

At the Infantry School Mailing List

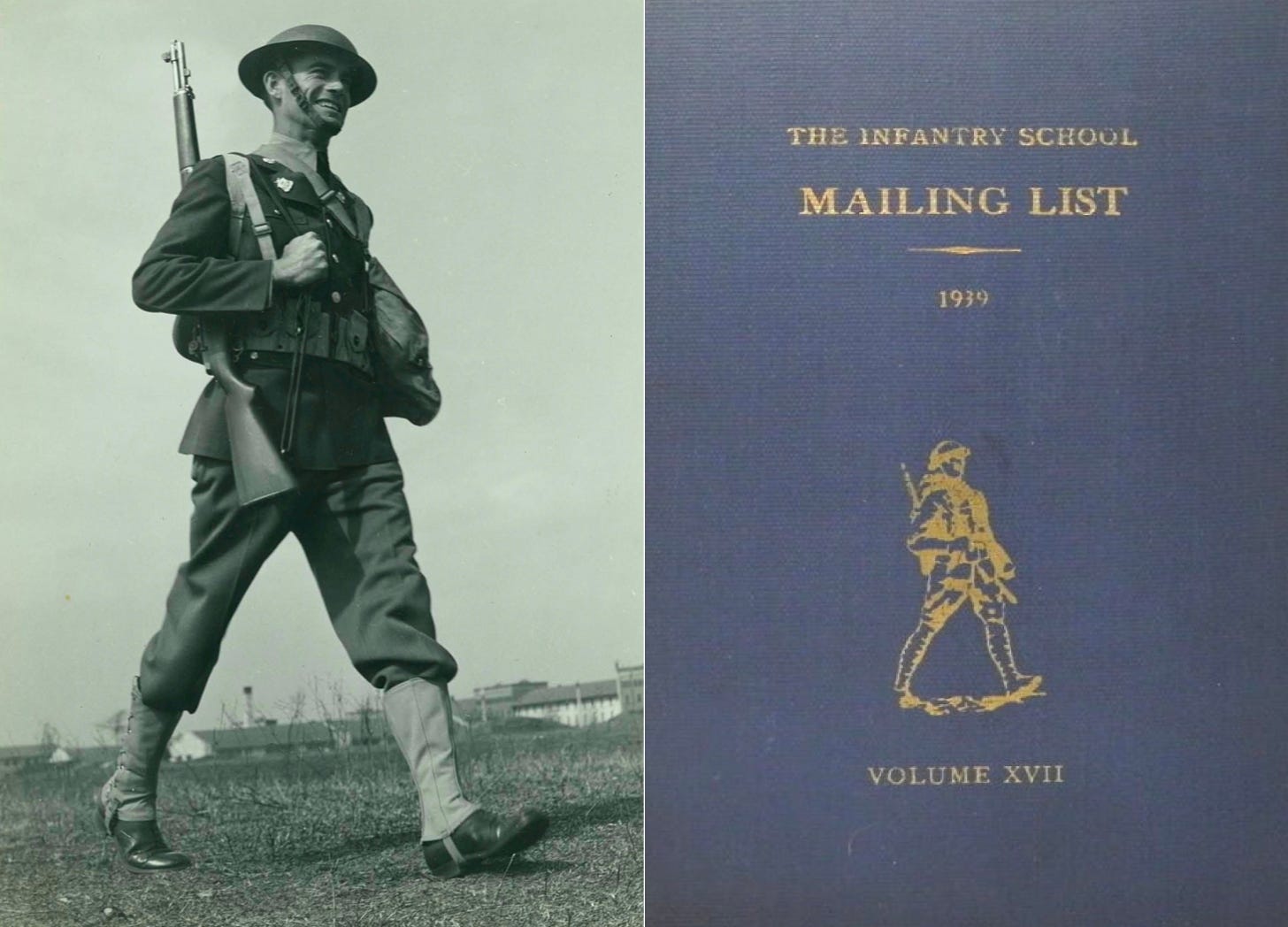

The issue of Infantry School Mailing List for January of 1939 began with a historical map problem. Called “The Battle at Rocourt,” this exercise, like others of its type placed participants in the role of a soldier who, at some point in the recent past, had faced a series of difficult decisions. (In particular, the problem asked readers to put themselves in the shoes of the commanding officer of French battalion that found itself in the path of a major German offensive in the spring of 1918.)

By itself, the publication of “The Battle of Rocourt” offered no surprises. After all, historical map problems had been had been a regular feature of the Mailing List since the summer of 1932. What was unusual, however, was the statement that preceded the mise en scène.

“Certain advantages as well as certain disadvantages are inherent in an historical map problem. The situation can not be set up so as to illustrate a particular tactical doctrine. On the other hand, the author cannot be accused of having so stretched and twisted incidents as to produce a situation that could not possibly arise. The situations in an historical map problem have actually existed and someone has been faced with their solution when a faulty solution might mean the lives of men. The situation is apt to be more vague, information less complete, and events less orderly than in a map problem conceived in the mind of the author. Many of the decisions in a historical map problem appear minor in a map problem - yet, remember that when these situations were faced by the commander either in battle or in that tense period preceding battle, their importance loomed large.”

Perusal of the issues of the Mailing List that followed that of January 1939 reveals a possible reason for this apology (in the classic sense of that word). “The Battle at Rocourt,” it turns out, was the last historical map problem to appear in the journal. Thus, it is easy to imagine that, as he prepared the exercise for publication, the anonymous author realized that his colleagues at the Infantry School at Fort Benning had come to prefer instructional methods of other sorts.

One of these alternatives was the “map problem conceived in the mind of the author.” Made popular by Eben Swift in the decades leading up to the World War, this was a fictional exercise in which all elements (save, perhaps, the ground) were depicted in their ideal form. Thus, a map problem of this sort featured things rarely found on actual battlefields: full-strength units, reliable reports, unambiguous chains of command, clear orders, full canteens, and temperate weather.

In the intellectual ecology of the US Army of 1939, the fictional map problem enjoyed two advantages. First, the schools at Fort Leavenworth, which many instructors at the Infantry School had attended prior to arrival at Fort Benning, made extensive use of such exercises. Second, they fit in nicely with “doctrine,” the scripted approach to tactics that the US Army had adopted soon after the return of the American Expeditionary Forces from Europe.

Sadly, the fears of the author of “The Battle at Rocourt” proved to be well-founded. In the issues of the Mailing List published between January of 1939 and the official entry of the United States into the Second World War, the pages previously allocated to historical map problems were filled with fictional map problems, doctrinal disquisitions (such as “Tactics of the Auto-Rifle Squad”), and, increasingly, material related to the care of the many new mechanical devices, particularly trucks, telephones, and radio sets, allocated to infantry units by the organizational reforms of 1938 and 1940.

Note: As a rule, when American soldiers (or Marines) of the 1930s used the term “map problem” (or “tactical problem”) without modification, they presumed that most (if not all) of the elements of the exercise in question were made up.

For Further Reading:

To Share, Subscribe, or Support:

The word "gamified" comes to mind.

Still, I think there are important tradeoffs here. It's much easier to run a gamified version of a historical scenario (or a scenario from whole cloth) since you can still try to teach the lessons learned without having to rely on context or ideas that would have been obvious to the leader at the time.

For example, something like the ability of a horse to traverse broken ground or pull a cart up a hill might be obvious to the officer at the time, but not to the person working through the problem today.

This is great.