The Critical Vulnerability of Hamas

Location, Location, Location

At the highest level a critical vulnerability is likely to be some intangible condition, such as popular opinion or a shaky alliance between two countries, although it may also be some essential war resource or a key city. At the lower levels a critical vulnerability is more likely to take on a physical nature, such as an exposed flank, a chokepoint along the enemy’s line of operations, a logistics dump, a gap in enemy dispositions, or even the weak side armor of a tank.1

For two weeks now, I have tried to reconcile what I have been learning about the war in Gaza with the theory of maneuver warfare. In particular, I have been attempting to determine if the concept of critical vulnerability has anything to offer to people trying to make sense of that conflict.

The first possibility that came to mind belonged to the realm of finance. What if, I wondered, the income that allows Hamas to pay its bills dried up? After some thought, and a bit of reading, I came to the conclusion that the flow of money, as critical to the survival of the organization as it might be, was far from vulnerable.

The Danegeld paid by Israel has clearly gone the way of Eric Blood-Axe.2 Other sources of funding, however, may well have grown as a result of the current war. Thus, it is quite possible that the attacks of 7 October 2023 resulted in an upsurge in donations from individual boosters. (I fear that the excitement, and, alas, the horrors, of that day have convinced many supporters of competing jihadi groups to change the object of their pecuniary affections.)

While I have no access to the spreadsheets of the Intifada Revenue Service, I would not be surprised if the yield from duties charged on the movement through the trade tunnels that connect Gaza to Egypt has increased as well. (The importation of considerable quantities of bottled water, propane canisters, preserved food, and solar cell-phone chargers has, no doubt, already begun. Similarly, I am confident that Hamas continues to take a cut of fees charged on the export of portable wealth and the egress of particularly privileged people.)

Hamas cannot function without the support of the people who live in Gaza. Thus, the intangible ties that bind the two together easily qualify as “critical.” The moral character of such connections, however, confounds attempts by any outside force to cut them. As in the story of the futile attempts by the wind to deprive a man of his overcoat, the greater the pressure on the relationship, the stronger it becomes.

To put things more plainly, attempts to use deprivation to drive a wedge between the people of Gaza and Hamas will only work if the most visible champions of the latter organization fail to share in the resulting hardship. Thus, the ostentatious enjoyment of an apple by the local ward heeler will do more damage to the relationship between people and party than any number of bombs, shells, or missiles.

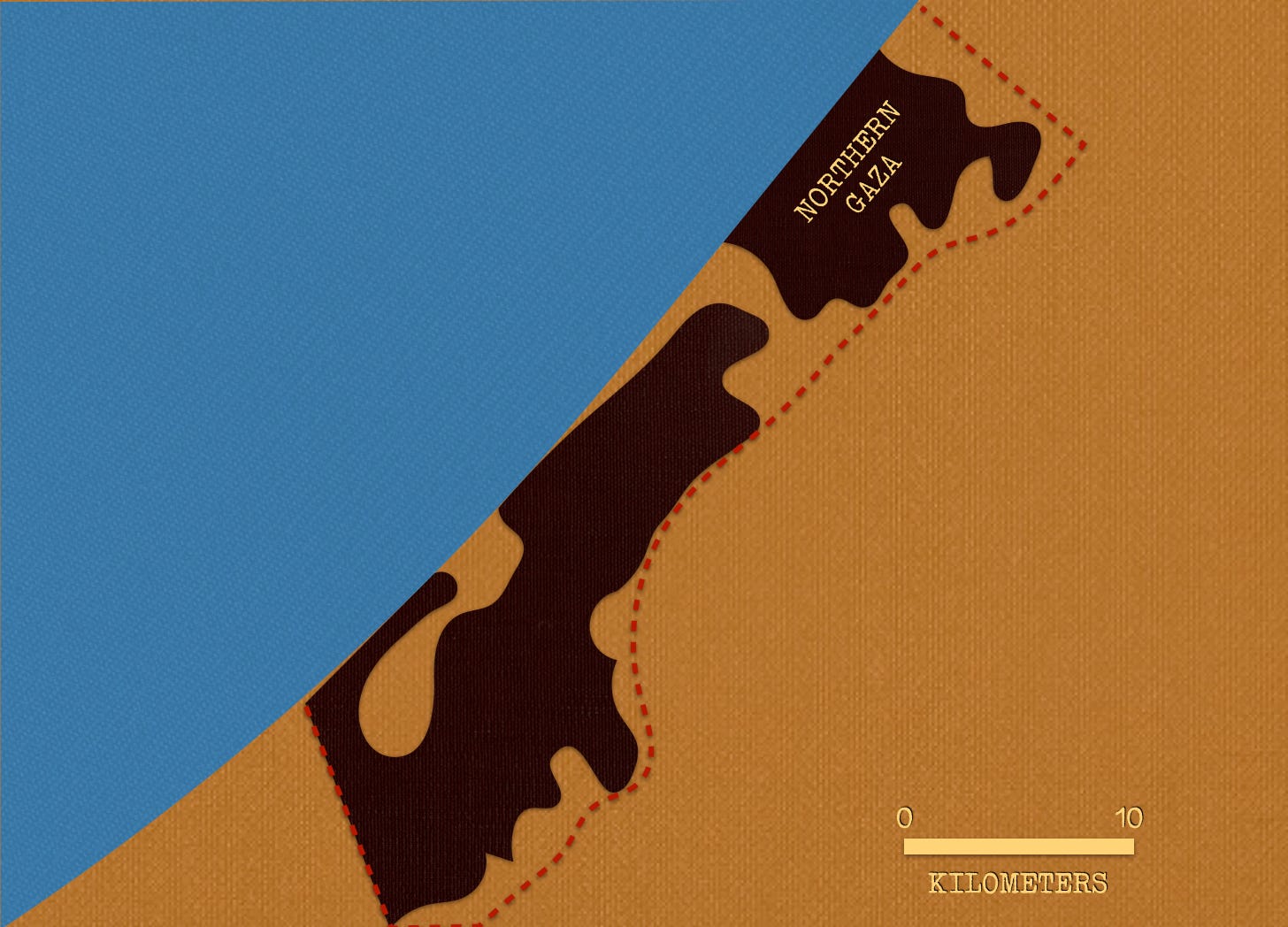

What bombs, shells, and missiles can do, however, is convert a city into a wasteland of collapsed buildings and impassable streets, and, in the course of doing that, force the people who live there to leave. This, in fact, is what the Israeli Defense Forces are doing to the place they call Northern Gaza, a conurbation that, until 7 October 2023, had been home to, as one says in South Asia, “ten lakhs of people.”3

Plenty of pundits presume that the ongoing bombardment of Northern Gaza serves chiefly to pave the way for the Einsatz of ground troops. I suspect, however, that, rather than attempting to take possession of the rubble, the Merkavot and their escorts will occupy blocking positions in the piece of (relatively) open ground that separates Northern Gaza from the rest of the Gaza Strip.4

Instead of preventing the passage of people coming from places plagued by contagious disease, the Israeli soldiers manning this cordon sanitaire will have three duties. First, they will protect the builders of a more permanent barrier. Second, they will forbid the return of former residents. Third, they will control the exits from what once was Northern Gaza, taking special care to capture, kill, or drive into the wreckage, anyone who looks like a fighter.

None of these effects will necessarily cause the people of Gaza to repudiate Hamas. On the contrary, this course of action may actually strengthen the bonds between Hamas and the people of Gaza. Indeed, there is a good chance that, in the years to come, people who lost their homes in Northern Gaza, what might be called “double refugees,” will be inclined to embrace Hamas and, in its absence, the most extreme of its successors.

Nonetheless, doing to Northern Gaza what the Romans did to Carthage exploits the critical vulnerability of Hamas and, by extension, any organization that might be tempted to reprise the attacks of 7 October 2023. Such parties, after all, rule over a people rich in sons and capable of enormous suffering, but poorly supplied with real estate.

Notes:

As with other articles related to this crisis, I have restricted the ability to post comments to paid subscribers.

An earlier version of this article conflated the conurbation of Northern Gaza with the municipality of Gaza City

United States Marine Corps Fleet Marine Force Manual 1: Warfighting (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1989) page 36

Can you tell that I have been listening to the Scandinavian History Podcast?

A lakh equals one hundred thousand.

Not to be confused with the governorate of North Gaza, “Northern Gaza” has no official status within the Gaza Strip. Rather, it consists of the cities and other communities that lie north of the open ground that divides the Gaza Strip into two heavily urbanized areas.

The extent of the rubble reflects the embeddedness of Hamas. The bombings are anything but indiscriminate.

Of course, the media, along with the Biden administration, is already spinning the myth of the “good” Gazan. According to this narrative, Gazans are actually opposed to Hamas but are afraid or can’t show their true feelings. When the Palestinians put forward an Adenauer or a de Gaulle as their leader, prepared to accept “two states for two peoples”, perhaps this myth will be accepted.

As an aside, your use of the word Einzatz to describe the IDF is beyond reprehensible with its implicit and insidious comparison to the Nazis. I suggest you edit your piece accordingly.

What about the demographics of the Gazans? Ages and sex ratio at each age? Also, I've heard that the Gazans are very secular, as Muslims go. Is that correct? I use the term Gazan rather than Palestinian, because I don't get the impression that the inhabitants have a common culture.