The 18th Artillery Division (I)

The Armies of the Second World War

In October of 1943, Army Group Center used the surviving pieces of a badly damaged armored division as the framework for a formation of an entirely new kind. The armored division in question, the 18th Armored Division, had lost most of its tanks, as well as much of its infantry, in the battle of Kursk. The new formation, the 18th Artillery Division, had no need of either tanks or infantry. It did, however, make full use of such elements as the division headquarters, the logistics infrastructure, and the field artillery regiment.

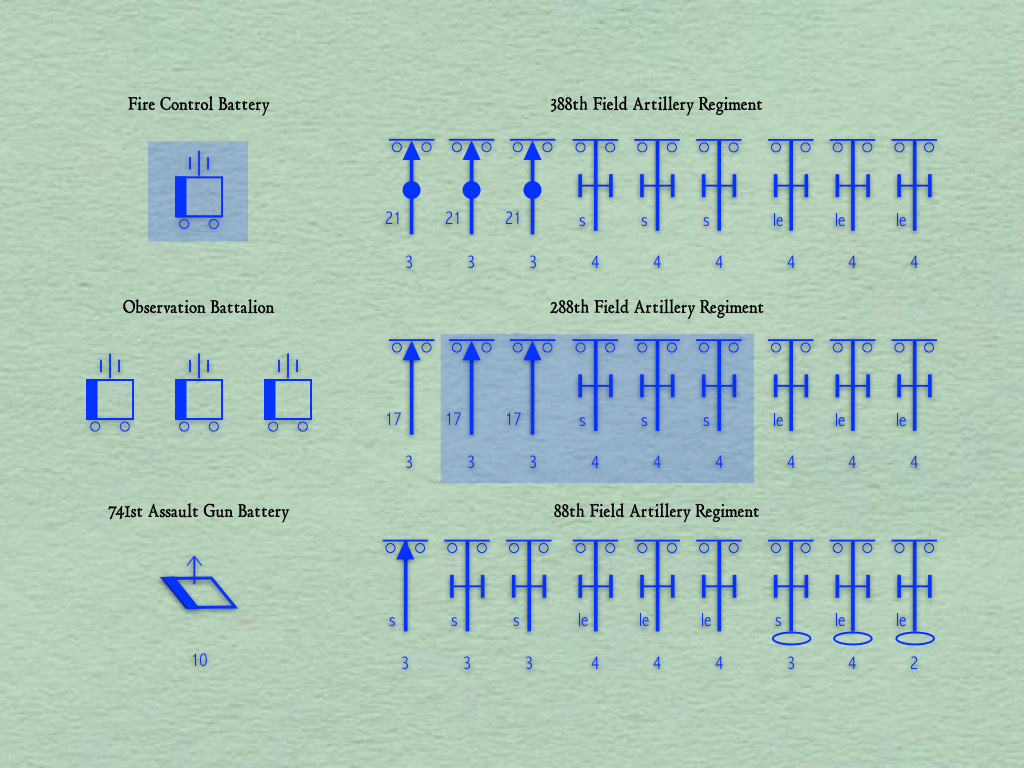

Like many other field artillery regiments serving with Armored Divisions in 1943, the 88th Field Artillery Regiment consisted of three battalions, each of which was armed with artillery pieces of a different sort. The First Battalion (I/88) operated self-propelled howitzers of two calibers (105mm and 150mm.)1 The Second Battalion (II/88) was equipped exclusively with 105mm howitzers of the towed persuasion. The Third Battalion (III/88) was a mixed heavy unit of the type that German gunners had begun to form in the First World War. It consisted of one battery of towed 105mm heavy guns and two batteries of towed 150mm heavy field howitzers.

One field artillery regiment, however, did not an artillery division make. So, to reinforce the fires of the 88th Field Artillery Regiment, the German authorities organized two additional regiments.2 One of these, the 288th Field Artillery Regiment, was distinguished by the possession of a large number of 170mm “heavier” guns.3 The other, the 388th Field Artillery Regiment, was well supplied with 210mm heavier howitzers. Both of the new regiments also fielded batteries armed with the typical weapons of the field artillery regiments of German infantry, motorized, and armored divisions: 105mm heavy guns, 105mm light field howitzers, and 150mm heavy field howitzers.

Artillery Batteries of the 18th Artillery Division

1 November 1943

So that it could move rapidly from one defensive crisis [Brennpunkt] to another, the the 18th Artillery Division was to be entirely motorized. So that the shells fired by a number of batteries might fall all at once on a single target (or set of targets), the formation was given an experimental Fire Control Battery (Feuerleitbatterie.) This unit translated information provided by observers into coordinated sets of firing data for as many as eighteen firing units. (The latter could be single batteries, whole battalions, or task groups of various kinds.)

The fire control battery supplemented, but did not replace, traditional German fire control procedures. Thus, the work of organizing most bombardments, whether carried out by individual roving guns [Arbeitsgeschütze] or groups of several batteries, remained in the hands of the officers commanding batteries, battalions, and regiments.

The Fire Control Battery maintained contact with a large number of observers. Most of these were forward observers of the ordinary kind, officers and non-commissioned officers who reported to the commanders of batteries and battalions. A few, however, worked for the division as a whole.

Observers of the latter type were experienced artillery officers who had been given the right to command (rather than merely request) the concentrated fire of any (or all) artillery pieces in range. When operating in open terrain, these officers rode in armored command vehicles escorted by assault guns. When using hidden observation posts, they employed portable radio sets.

For counter-battery work, the 18th Artillery Division enjoyed the services of an organic observation battalion. Identical to the observation battalions that were often attached to army corps, this unit performed three tasks.

the establishment of a network of sound-ranging stations, flash-ranging observatories, and observation balloons

the conduct of surveys to put all batteries, ranging stations, and observers on the same grid

operational control over the counter-battery effort

In situations where the 18th Artillery Division supported an army corps with an an observation battalion of its own, the two observation battalions would agree on a division of labor. As a rule, this meant that the local observation battalion would take charge of the counter-battery effort, leaving the 18th Artillery Division focus its efforts on crises and decisive opportunities [Brennpunkte und Schwerpunkte] in the battle as a whole.

Sources: Wolfgang Paul, Geschichte der 18. Panzer-Division 1940-1943 Mit Geschichte der 18. Artillerie-Division 1943- 1944, (Reutlingen: Preußischer Militär-Verlag, 1989), pp. 288-91 and documents of the 18th Artillery Division on file at the U.S. National Archives, Captured German Records, Microfilm Series T-315.

Strictly speaking, none of the howitzers of the 18th Artillery Division were true howitzers. Rather, all were gun-howitzers.

The number “188,” which was used to designated the field artillery regiment of the 88th Infantry Division, was already spoken for.

German gunners of the first half of the twentieth century classified artillery pieces as “light” [leicht] (e.g. 75mm guns and 105mm howitzers); “heavy” [schwer] (e.g. 105mm guns and 150mm howitzers); “heavier” [schwerer] (e.g. 170mm guns and 210mm howitzers); and “heaviest” [schwerste] (Big Bertha and her siblings.)

Fascinating how organization was used to overcome the limits of communication technology.