Rules for Military Writing

A very short guide

Good military writing resembles good civilian writing. It employs short sentences and active verbs. It eschews passive constructions and bureaucratic language. Most of all, it avoids clichés like the plague.1

That said, military writers must take special care to avoid temptations peculiar to their profession. In particular, they must be careful with terms of art, make good use of illustrations, and employ acronyms like Icelandic cooks of the last century used spices (sparingly, if at all.)

Military terms of art present peculiar problems, if only because the combination of familiar words can yield expressions with meanings that differ from those of their component parts. Thus, for example, “reconnaissance-strike” does not refer to a strike conducted by a reconnaissance unit, “operational art” has little to do with the work of the battalion operations officer, and “maneuver warfare” involves far more than the maneuver of maneuver units.2

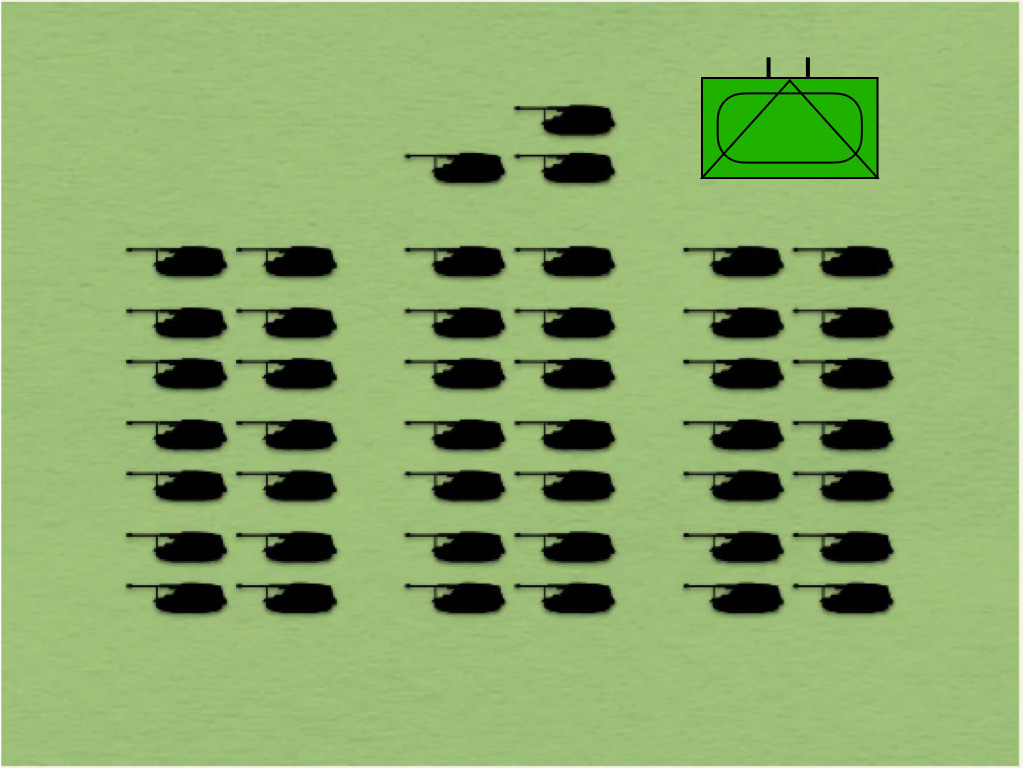

As military writing deals with things that military units do on battlefields, the military writer will often want to illustrate his work with organizational charts and maps. If, moreover, he wishes to communicate the relevant facts to his readers, he will create these in ways that are as simple as possible. Thus, for example, an “infographic” that shows a little picture of every self-propelled armored anti-tank gun in a battalion may do a better job of explaining that organization to your readers than the standard map symbol for a unit of that sort.

When it comes to maps, there are two rules. The first of these is Cancian’s Law. “Every place mentioned in the text should be indicated on a map.” The second is Gudmundsson’s corollary to Cancian’s Law. “The map should only show places that are mentioned in the text, unless the places are so famous that they help readers orient themselves.”

As far as acronyms go, the military writer will do well to avoid them altogether. First of all, they are created so easily, and expire so quickly, that most readers will have no idea what a given acronym means. Secondly, they rarely convey the nature of a given phenomenon than ordinary words. After all, “city fighting,” “struggle for control of a town,” and “combat in a strip mall,” tell the reader a lot more than MOBUA (Military Operations in Built-Up Areas) or MOUT (Military Operations in Urban Terrain.)

If the military writer is obliged to use a particular acronym, he is well advised to limit himself to one such construction for each paragraph that he writes. Indeed, if he exceeds this upward limits, the results are likely to be FUBAR (Fouled Up Beyond All Recognition.)

Note to American readers. This is an example of what our British cousins call “irony.”

It’s interesting to note that all three expressions mentioned in this paragraph owe their existence to the translation of expressions coined by Soviet military theorists.

Now if you could only get the wonks in the five (5) sided puzzle palace aka pentagon to listen to you!! How about a correspondence course! Like in the old days when you could go to AWS (amphibious warfare school) via Marine Barracks 8th and I!! It does seem so that precise, clear language untroubled by wonk speak gets the point across more vibrantly. Like a “model” drawn in the dirt with rocks and sticks to bring the 5 paragraph operations order into sharp focus for every rifleman in the rifle platoon....

Victorian military writers did not yet possess the contemporary cornucopia of neologisms and acronyms, which themselves decay into nonsensical syllables and hence become simply new, opaque and ugly words. Their descriptions sometimes take on a degree of abstraction, such as a battalion that throws itself athwart the advancing enemy's path. But usually there are vignettes where blood and dirt and weapons and horses and smoke and other tangible things are described in ordinary language, and a vivid image is left with the reader. Somehow the idea has arisen that this sort of thing is less than professional. So much the worse for the professionals who read contemporary military writing and have to try to learn from it.