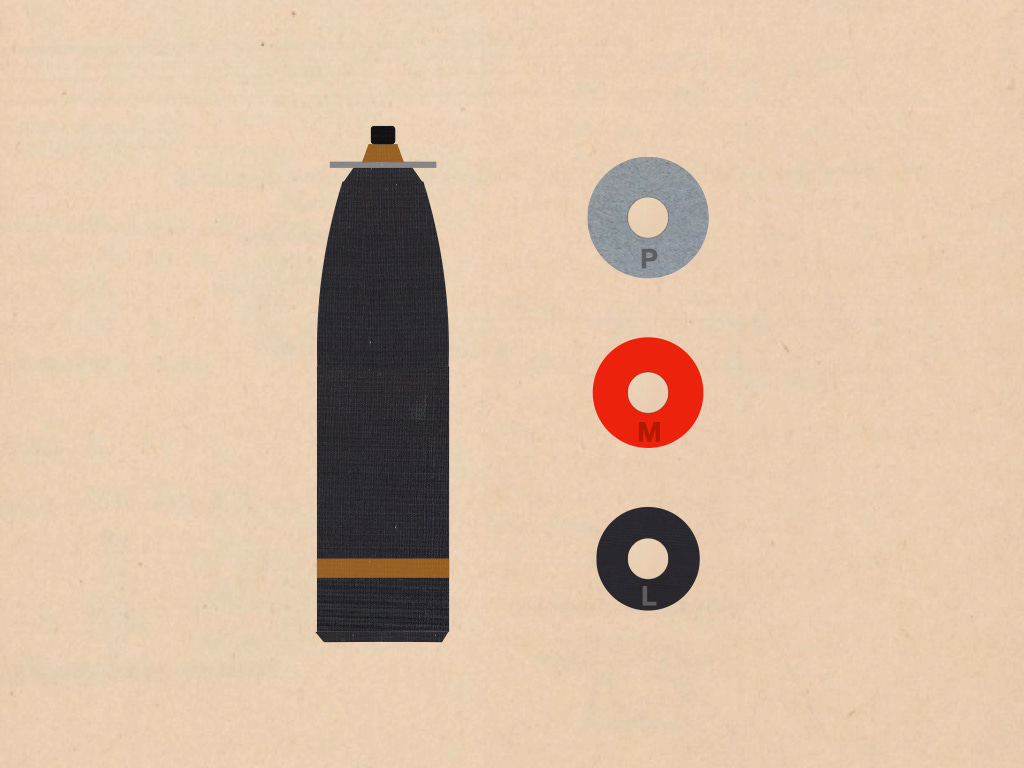

The shells fired by the “French seventy-five” flew faster than those fired by most of the other weapons of its class.1 Indeed, of the many light field guns adopted at (or soon after) the end of the nineteenth century, only two imparted more speed to their projectiles than the 75mm field gun, Model 1897.2 (These were the two three-inch field guns made for the Russian Army by the Putilov works in St. Petersburg.)

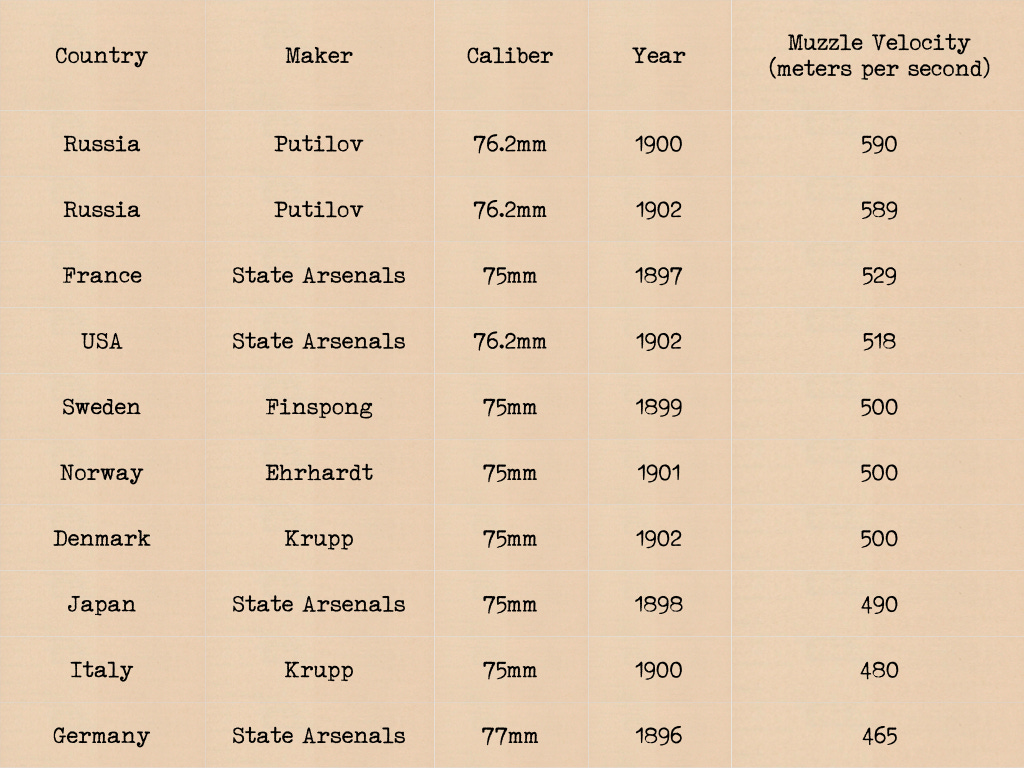

Edwardian gunners valued velocity because, all other things being equal, a faster shrapnel shell imparted more speed to the musket balls that it carried, thereby making them more destructive than they would otherwise have been. This advantage, however, came at a price. Because they flew so fast, the projectiles fired by the French seventy-five followed a flat trajectory. This, in turn, made it hard to rain lead (or, in the case of high explosive shells, pieces of steel) upon foes taking shelter in ditches, gullies, or trenches, as well as enemies located on the reverse slopes of many hills.

The German solution to this problem involved two complementary measures. First, the German armies adopted a field gun with relatively low muzzle velocity. Second, they acquired a large number of light field howitzers. With a muzzle velocity of 305 meters per second, the latter lobbed shells that rose high into the air before falling to the ground.

Some French gunners wanted to address the problem of defiladed foemen by acquiring howitzers comparable to those of the German Empire. Others proposed the mounting of existing field guns on a split-trail carriage. One, however, came up with a much less expensive solution.

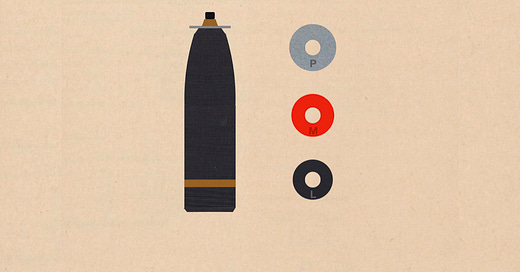

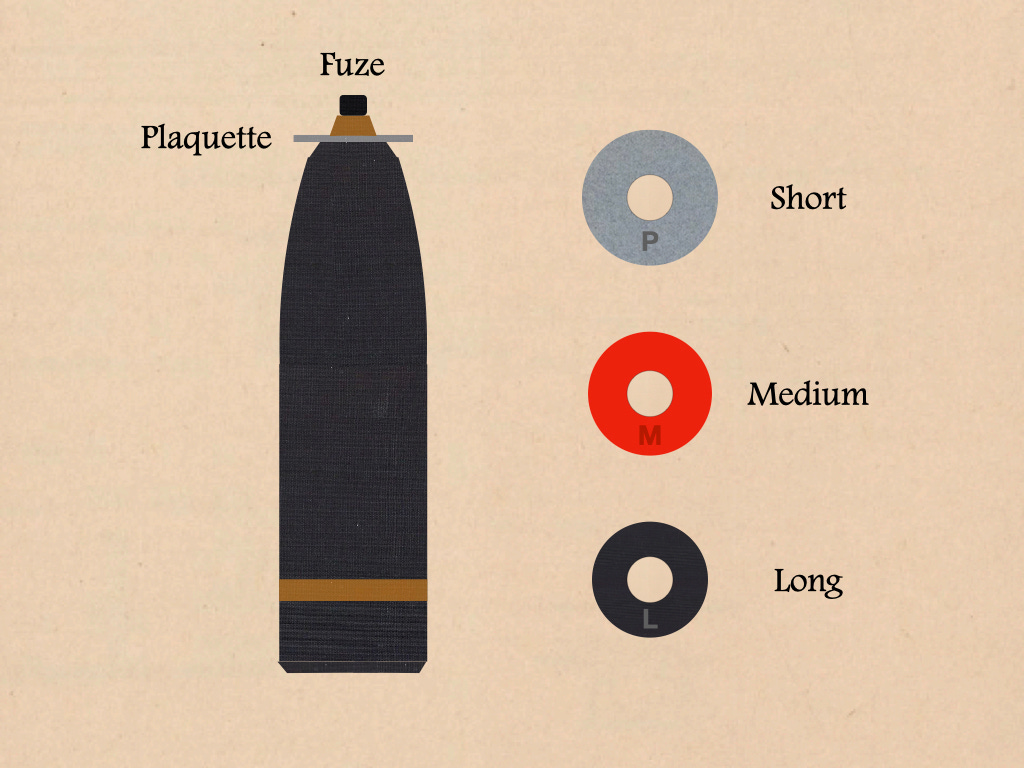

Hypolyte Malandrin bored a hole in a simple metal disk, thereby creating a device that might be described as a close cousin of the kind of washer that one might find at a present-day hardware store.3 When placed between the nose of the shell and its fuze, this plaquette interfered with the flow of air over the (otherwise aerodynamic) front of the shell.4 This, in turn, deprived the shell of some of its speed and, at the same time, added considerable curvature to its trajectory.

At first, Captain Malandrin, who was then serving as the director of the state cartridge factory at Douai, seems to have imagined his invention as a tool for preventing the ricochet of shells fired in training. However, by the time that the plaquette came to the attention of the French public, he had begun to view it as a means of reaching targets in defilade.

In 1913, a group of parliamentarians proposed the appropriation of funds for the purchase of light howitzers for the French Army. (Some of these legislators imagined that the piece in question would be a 105mm howitzer similar to the one used in Germany. Others thought that the French Army ought to acquire 120mm howitzers similar to the 122mm piece that the Schneider works had recently made for the Russian Army.)

Those who opposed the bill argued that, when fitted with plaquettes Malandrin, 75mm field gun shells could do all of the things expected of projectiles fired by light field howitzers. Thus, rather than spending sixty million francs on brand new artillery pieces and a stock of ammunition, the Republic could solve the problem at hand with a drill press and some sheet metal. (In those days, a French franc could be had for twenty or so American cents.)

French gunners of the First World War made little use of the plaquette Malandrin. One reason for this was the pernicious effect of the disks on the ability of shells to land, and explode, at the proper place and time. Another was the limit that the disk placed on range.5 In a war in which 75mm field guns frequently shot at targets at distances of 6,000 meters or more, a shell sporting a plaquette could fly no further than 4,000 meters.6

Nonetheless, the French Army of the postwar years retained its stock of plaquettes Malandrin. Thus, as late as 1936, students in the school for artillery officers learned about the devices, the ways in which they could be used, and the meanings of the letters etched upon them: P for près (“near”) and L for loin (“far.”) (The M found on some surviving plaquettes seems to stand for moyen, meaning “medium.”) They also learned that plaquettes were used with the shells fired by the short-barreled 75mm guns installed in French tanks of the larger sorts.)7

For Further Reading:

The term “French seventy-five” was coined by Americans looking for a way to distinguish the piece from other 75mm field guns employed by the US Army. As might be imagined, when speaking informally, French people called it “the 75” or “our 75.”

Most of the figures used in the table come from the foldout chart (marked Anhang) included with Wilhelm Heydenreich, Das Moderne Feldgeschütz [The Modern Field Gun] (Leipzig: Göschen, 1906), Volume II. The figures for the two Russian field guns come from Yevgeniy Zakharovich Barsukov, Russkaya artilleriya v mirovuyu voynu [Russian Artillery in the World War] (Moscow: 1938), Volume I, page 31. (Readers can find a digital copy of the latter book on this Russian website.)

In 1889, after graduating from the École Polytechnique, Hypolite Malandrin accepted a commission as a second lieutenant of artillery. In 1900, while serving in China with the international expeditionary force sent to suppress the rebellious Boxers, he presided over the debut of the new 75mm field gun. Régis Voyron Rapport sur l’Expedition de Chine, 1900-1901 (Paris: Charles-Lavauzelle, 1904) pages 245 and 464

Were I not the author of Pardon My French, a light-hearted guide to French phrases used (and abused) by people in the Anglophone world, I would describe the plaquette Malandrin as a piéce de résistance.

Martial Justin Verraux “Les Obusiers Légers de Campagne” Pages de Gloire (5 Décembre 1915) page 11

École Militaire de l'Artillerie École de Commandant de Batterie: 1er Partie, Canon de 75 (Paris: Chapelot, 1917), page 47 (Note: Gallica has mistakenly filed this volume under the title of Artillerie Lourde.)

École d’Application d’Artillerie Organisation des Matériels d’Artillerie: Tome I, Munitions (Fontainebleau: Lithographie de l'Ecole d'Application d'Artillerie, 1936) page 63