In the English speaking world, the name Gallipoli invariably evokes memories of the great events of 1915 and 1916. A location of such strategic importance, however, rarely serves as the site of a single battles. Two years before the landings of the British, Indian, Australian, and New Zealand troops on the south-west portion of the the peninsula (and the concurrent French landings on the nearby mainland of Asia Minor near the ruins of the ancient city of Troy), Ottoman soldiers defended the Dardanelles against the forces of the Balkan League.

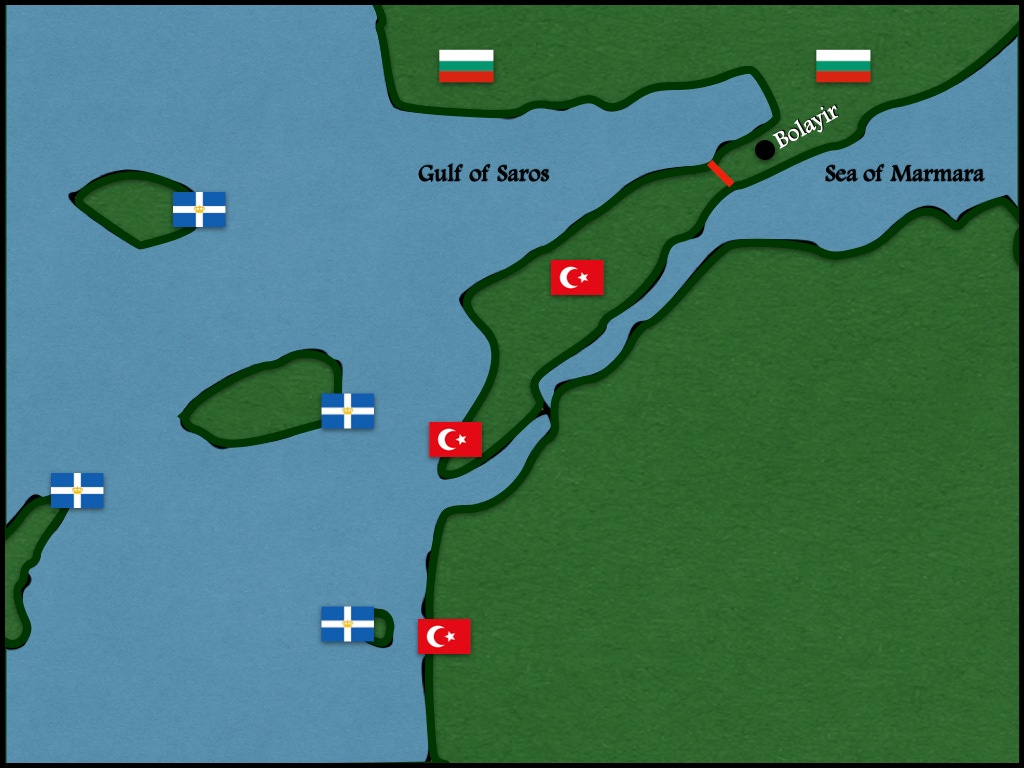

By the end of November of 1912, the combined efforts of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro, and Bulgaria had driven Ottoman forces from most of “Turkey in Europe.” Indeed, the only intact Ottoman formations on European soil were those trapped in fortresses, those defending the fortified line just west of Constantinople, and those holding the Gallipoli Peninsula.

Soon after arriving, the Ottoman forces on Gallipoli began to build a belt of field fortifications across the narrowest part of the peninsula, a line some five kilometers (three miles) west of the the town of Bolayir. At the same time, they occupied outposts some twenty kilometers east of the line, at the place where the peninsula connected to the mainland.

On 4 February 1913, the Bulgarians attacked. On the first day of this attack, they drove in the Ottoman outposts. On the second day, they broke through a hastily erected line of resistance, thereby convincing the Ottoman forces in front of them to evacuate Bolayir. However, rather than taking the town, or otherwise attempting to exploit their victory, they withdrew to positions some ten kilometers (six miles) east of the Ottoman earthworks.

While the Ottoman land forces returned to the earthworks along the neck of the Peninsula, ships of the Ottoman Navy operating in the Sea of Marmora located, and began to bombard, the Bulgarian forces near the coast. This caused the Bulgarians to move inland, where they took up, and improved, new positions on the rear slopes of nearby hills.

On 9 February, the Ottomans launched a double attack. While the main body of the Ottoman garrison of Gallipoli advanced overland, a smaller force, supported by the fire of Ottoman warships, landed on the far side of the Bulgarian position. Notwithstanding the advantages, both numerical and geometric, enjoyed by the Ottoman attackers, this pincer action failed to destroy the Bulgarian force. Indeed, in the course of two failed attacks, the Ottomans suffered some ten thousand casualties.

Though the Ottoman maneuver failed to dislodge the Bulgarians from their trenches, the two-sided attack convinced the Bulgarian commander to seek ground that was, at once, both easier to defend against terrestrial attack and less vulnerable to naval gunfire. He found this on the east bank of a river, thirteen kilometers (eight miles) northeast of Bolayir and ten kilometers (six miles) north of the place where the Ottoman landing had taken place.

The Ottoman commander lost no time filling the vacuum. On 10 February, the Ottoman X Army Corps, recently sent out from Constantinople, landed on the north shore of the Sea of Marmora. That same day, the land-based force marched north. On the following day, both attacked the Bulgarian position, forcing the defenders to retreat towards the north, with Ottoman cavalry in hot pursuit.

While this was going on, yet another force entered the fray. Composed of Serbian, Greek, and Bulgarian forces delivered by Greek ships to the coast of the Gulf of Saros, this small army took the advancing Ottomans in the flank.

Yet again, the tide of battle turned. The Ottomans retreated to their fortified line west of Bolayir, where, on the evening of 12 February 1913, they withstood Greek, Serbian, and Bulgarian attacks for more than twelve hours. (On the western side of the line, the attackers benefitted from the fire of Greek warships in the Gulf of Saros. On the eastern side, the defenders enjoyed the support of Ottoman warships in the Sea of Marmora.)

Early on the morning of 13 February, the Allies called off their attack. This led to a pause in major operations which ended on 21 February, when a major Ottoman attack pushed the Greeks, Serbians, and Bulgarians back to their old positions. Once this had been achieved, however, X Army Corps moved into positions on the southern half of the Gallipoli Peninsula.

This deployment, the Ottoman leadership believed, would prevent Allied landing forces from attacking the coastal batteries that kept Greek ships out of the Dardanelles. This, in turn, would keep the Greek fleet from sailing into the Sea of Marmora, thereby threatening both the Ottoman capital of Constantinople and the line of fortifications that stood between it and the main body of the Allied armies.

Sources: Carl Hauska, “Der Balkankrieg, 1912/13”, Schweitzerische Monatschrift für Offiziere aller Waffen, 1914, pages 358-367 and (for the organization of X Army Corps) Hans Rohde, Die Operationen an Den Dardanellen im Balkankriege 1912/13 (Berlin: R. Eisenschmidt, 1914), page 134

For Further Reading:

To Share, Subscribe, or Support:

The battle that launched Ataturk's career!