The estate of the late John Sayen has graciously given the Tactical Notebook permission to serialize his study of the organizational evolution of American infantry battalions. The author’s preface and the previous section of this book may be found via the following links:

As Lieutenant Colonel Sayen left us before he could put the finishing touches on his manuscript, I have taken the liberty of punctuating the presentation of his work with posts that fill gaps, expand upon points made, and provide context. Readers can distinguish between elements of the original work and the additional material by looking at the author listed under the title of each post.

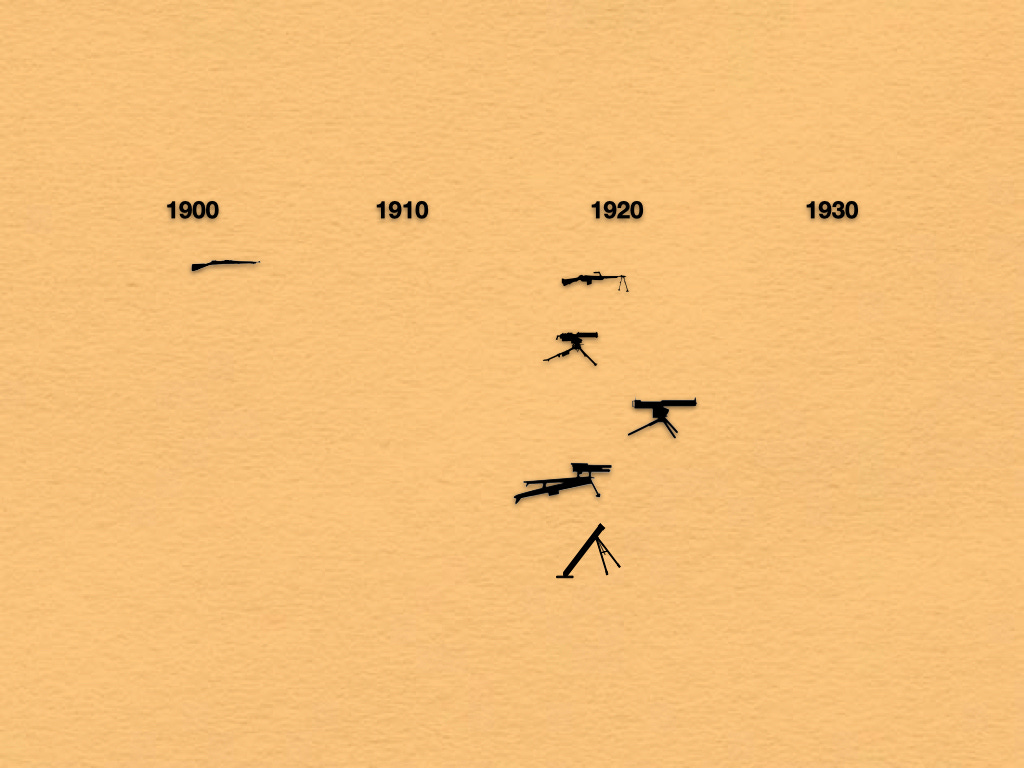

The experiments in the organization of infantry units conducted by the 29th Infantry at Fort Benning in 1929 and 1930 made exclusive use of existing weapons. That is, the various types of platoons, companies, battalions, and regiments tested were armed with weapons that had already been officially accepted into the armory of the United States Army. Of these, moreover, most were of types that had been in general use since the last year of the World War.

On 2 December 1930, in testimony before the Military Affairs Committee of the House of Representative of the US Congress, the Chief of Infantry, Stephen Ogden Fuqua, gave two reasons for the retention of these older weapons. The first was the fact that the Army possessed large numbers of such weapons. The second was his belief that these weapons were “efficient and compare favorably with infantry arms in use by the armies of the world.”

Notwithstanding his second point, Major General Fuqua followed his defense of the existing armament of American infantry units with a list of improvements that were underway. These included:

a semi-automatic rifle (to replace the M1903 Springfield bolt-action rifle)

a light machine gun

an air-cooled barrel for the M1917 .30 caliber machine gun

a new 75mm mortar

Two of the aforementioned projects resulted in a pair of soon-to-be iconic weapons: the M1 Garand rifle and the M1919 medium machine gun. (Both of these weapons were adopted in 1936.) The other two, however, did not fare so well. While the development of a light machine gun would remain on the proverbial “back burner” for a dozen years, the program to developed a new 75mm mortar lasted for less than two years. In place of that weapon, the Army adopted a close copy of the standard medium mortar (mortier Stokes-Brandt de 81 Modèle 27/31) of the contemporary French Army.

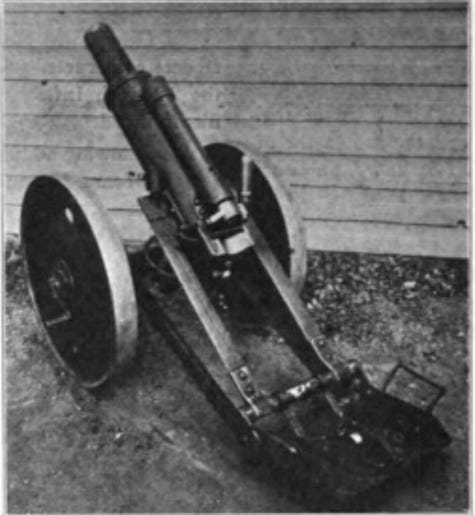

Between 1922 and 1932, weapons designers of the Ordnance Branch developed five 75mm mortars. Four of these were rifled, breech-loading weapons mounted on wheeled carriages. One, the M2, was a smoothbore. Thanks largely to the finned projectile designed by French polymath Edgar Brandt, the 81mm mortar delivered a more powerful payload than any of these weapons. At the same time, it enjoyed considerable advantages in rate-of-fire, range, and, most of all, accuracy.

Sources: Articles from the series, “Notes from the Chief of Infantry” that were published in the following issues of the Infantry Journal.

January 1925, pp. 82-83

September 1927, p. 290

May-June 1931, p. 245

May-June 1932, p. 215

July-August 1932, p. 297

For a thorough description of the 81mm mortar, see Louis E. Hibbs, “The Stokes-Brandt 81mm Mortar” The Field Artillery Journal, July-August 1932, pp. 357-372