An Ideal Regiment (1930)

Battalion: An Organizational Study of United States Infantry

The estate of the late John Sayen has graciously given the Tactical Notebook permission to serialize his study of the organizational evolution of American infantry battalions. Guides to other posts in this series can be found at the end of this post, in the section marked “for further

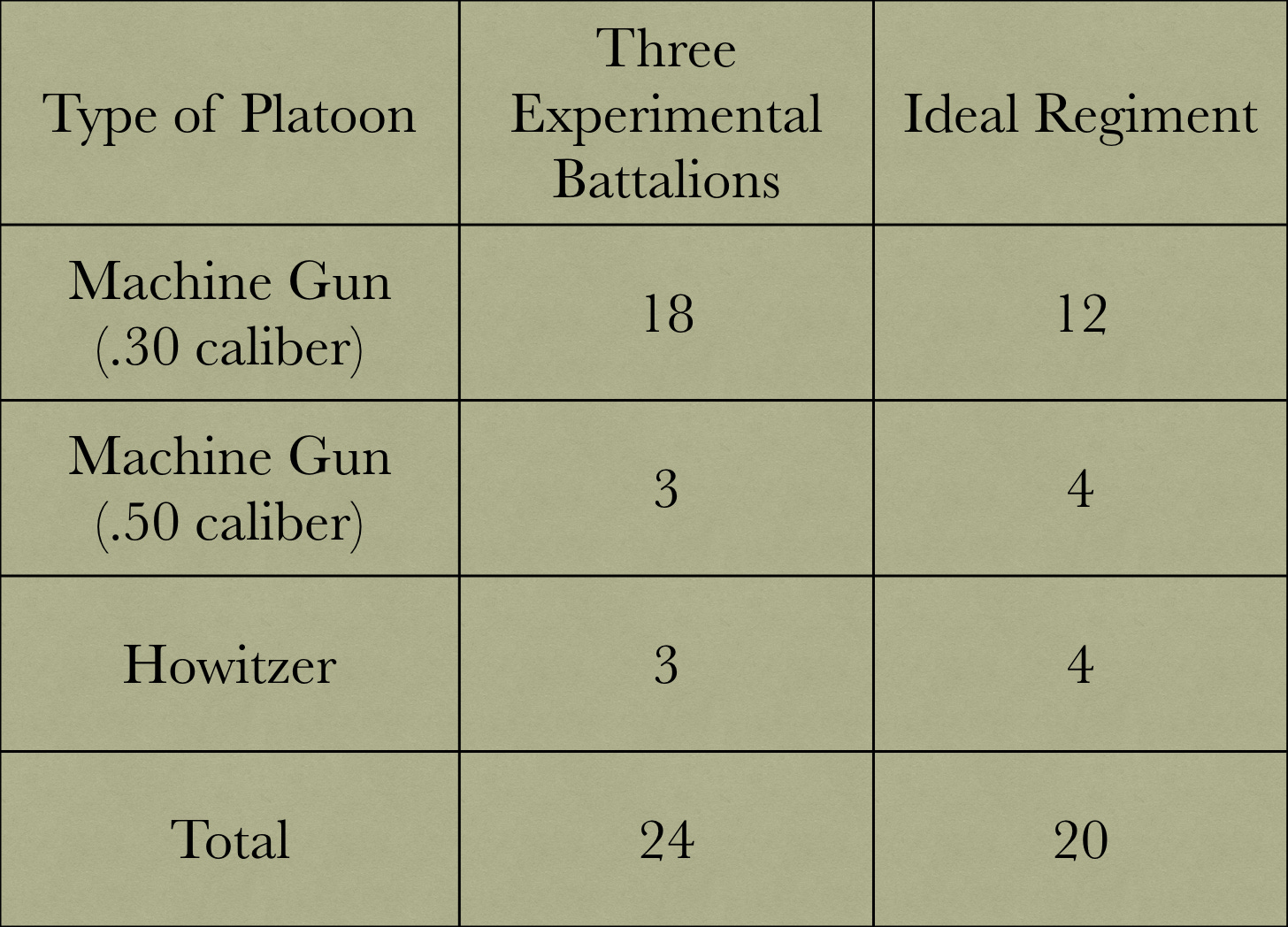

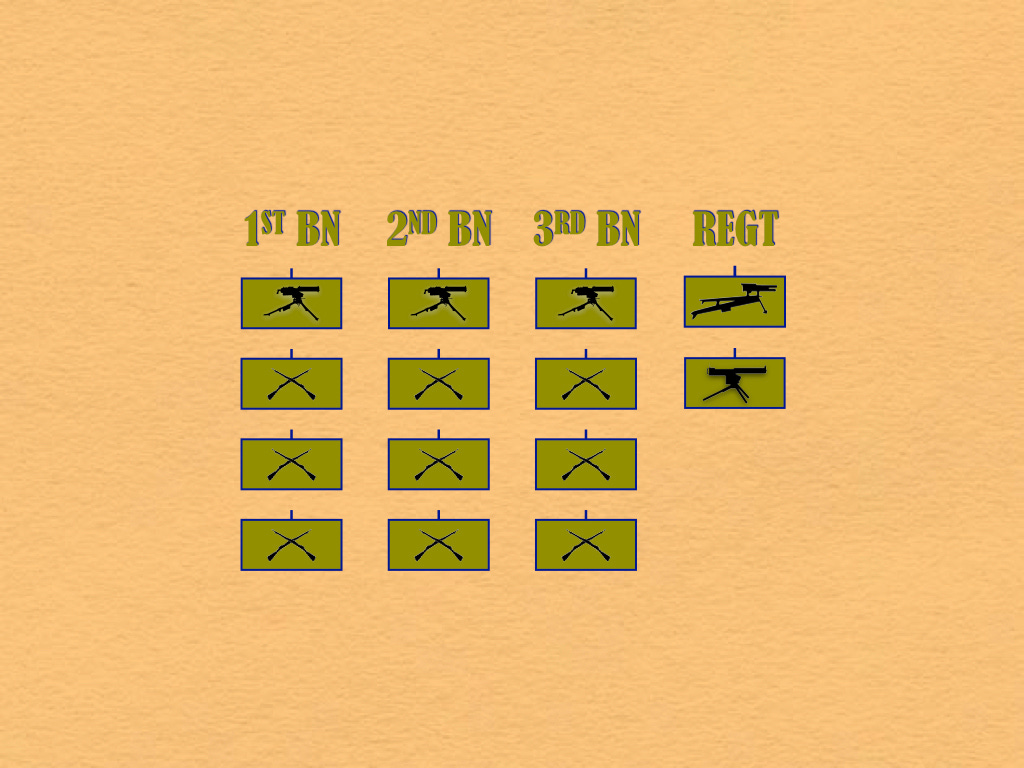

After completing its plan for the experimental battalion, the Infantry Board tackled the task of designing an ideal infantry regiment. As might be expected, the basic building block of the larger unit was to the aforementioned battalion. However, in order to fit three battalions of that type into a regimental framework, the Board changed the location, number, and armament many heavy weapons platoons.

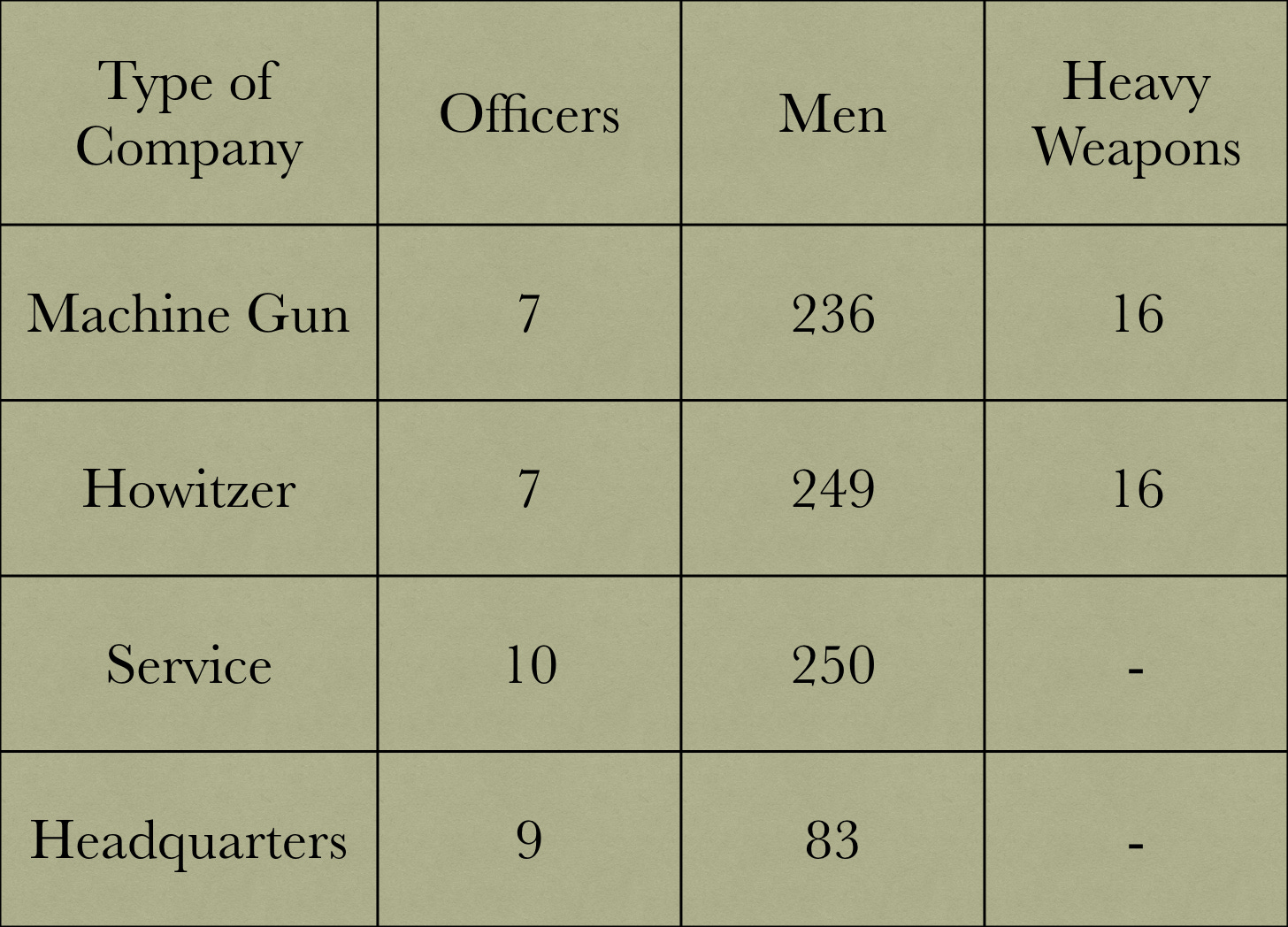

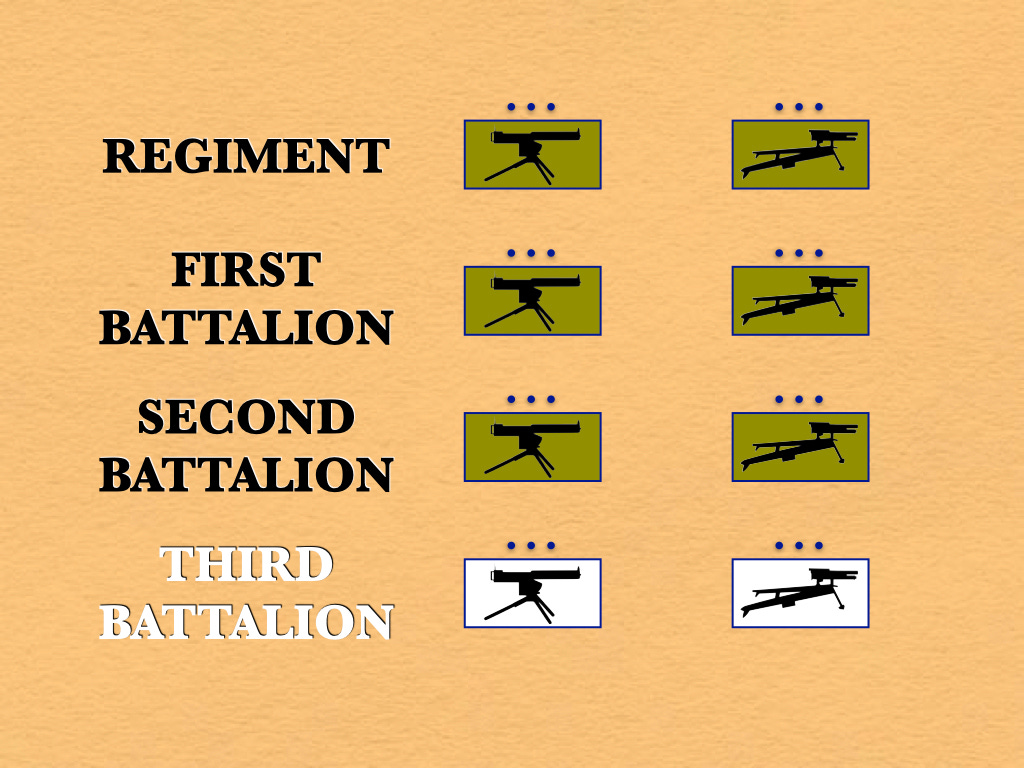

The Infantry Board assembled the twenty heavy weapons platoons of the ideal regiment into five companies, each of which consisted of four identical platoons. It then assigned one of these companies (armed with .30 caliber machine guns) to each of the three battalions and two to the regiment as a whole. The Board armed one of the regimental heavy weapons companies with .50 caliber machine guns and the other with a combination of mortars and 37-mm (‘one-pounder’) infantry guns.

In addition to three battalions and two regimental heavy weapons companies, the Infantry Board provided its ideal regiment with a headquarters company, a service company, and attachments from the Medical and Chaplain Corps.

As imagined by the Infantry Board, the service company was chiefly concerned with the horse-drawn vehicles that carried the regiment’s supplies. Indeed, half of the officers of the service company (5 out of 10) and four-fifths of the men (200 out of 250) served in the transportation platoon.

In much the same way, the Infantry Board designed a headquarters company in which the lion’s share of the men served in the regimental band. (The latter, which consisted of one warrant officer and forty-nine musicians, would take the place formerly occupied by a pioneer platoon.)

The organization of the ideal regiment facilitated the reinforcement of individual battalions, thereby enhancing their ability to operate independently. That is, the Infantry Board made provision for situations in which the regimental commander would attach a platoon of .50 caliber machine guns, a platoon from the howitzer company, and a section of the transportation platoon to a battalion.

In addition, the modularity of the ideal regiment fit in nicely with a plan to configure the 29th Infantry Regiment as a cut-down version of the ideal regiment. That is, the school troops unit of the Infantry School would possess two (rather than three) battalions, a howitzer company of three (rather than four) platoons, a regimental machine gun company of three (rather than four) platoons, and a service company that was missing one of its transportation sections.

The Infantry Board seems to have designed the ideal regiment for tactics that resembled the ‘delaying resistance’ [hinhaltende Widerstand] employed by the armies of the German Empire in the last few months of the First World War. That is, members of the Board imagined situations in which the fire of field pieces and machine guns would enable infantry divisions to hold relatively wide frontages, thereby preventing a larger enemy force from exploiting its advantage in numbers and, at the same time, setting the stage for independent action by individual battalions.

Sources:

“Notes from the Chief of Infantry - Reorganization of the Divisional Infantry” Infantry Journal (July 1930) pages 87-89

“The Provisional Infantry Reorganization” The Infantry School Mailing List Vol I (1930-31) pages 13-25

For Further Reading:

To Share, Subscribe, or Support: