After the end of the First World War, the private companies that made artillery pieces faced a saturated market. The vanquished were obliged to dispose of their existing stocks and forbidden to obtain new material. The victors had far more in the way of guns and howitzers than they needed to equip their peacetime armies. Neutrals could buy used weapons at fire sale prices, while the new states that emerged from the wreckage of empires could equip their batteries with the abandoned property of their former masters.

The great exception to this rule was the market for pack artillery. One reason for this was demand. In places like Morocco and Afghanistan, colonial authorities withdrew the concessions and halted the subsidies that had kept the peace during the Great War. Thus, there was a great increase in the incidence of frontier fighting, nearly all of which took place in regions unsuited to the employment of conventional artillery.

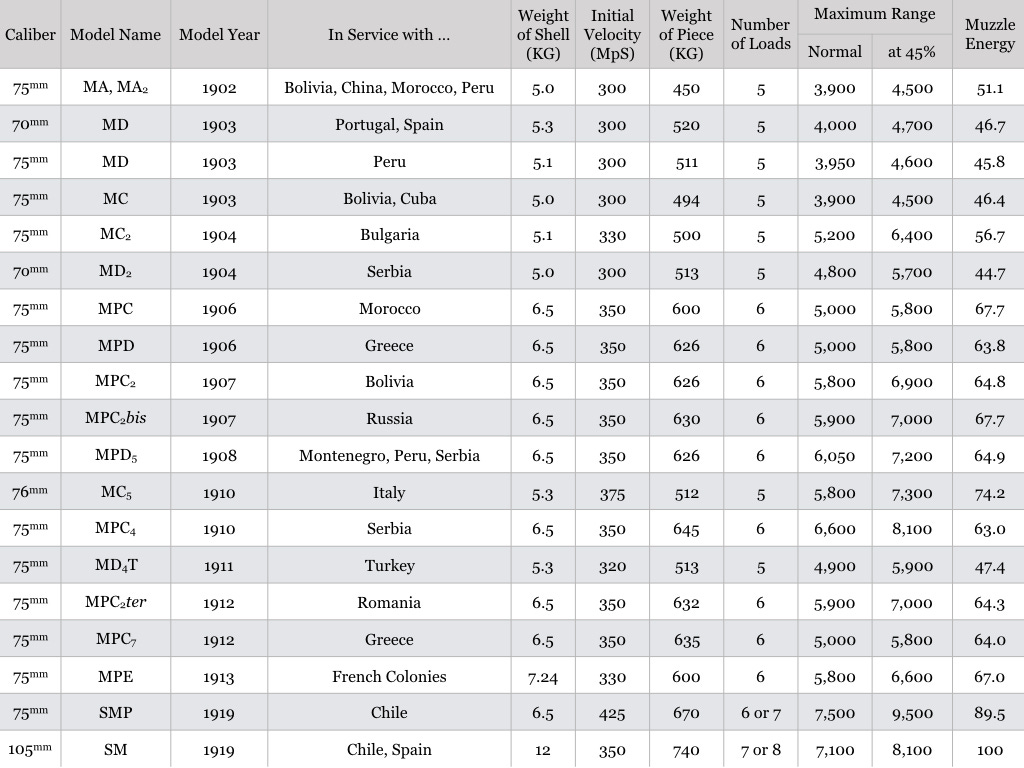

Another stimulant of demand for mountain guns was the steady improvement in the capabilities of such weapons. During the first twenty years of the twentieth century, a series of small improvements to metallurgy and the design of various components resulted in pieces that short larger projectiles out to greater distances, with greater striking power at the end of their journeys. The newer weapons were also easier to put together, and take apart, than their predecessors.

Source: A. Mortureaux, “Considerations sur l’Artillerie de Montagne,” Revue d’Artillerie, August 1922, pages 158-188