By 1806, the year of the catastrophic defeat of the Prussian army at the twin battle of Jena - Auerstadt, there were about 2,000 Jäger in the service of the King of Prussia. Parceled among the various detachments of the Prussian army for service as scouts or military policemen, they were, however, unable to do much to prevent the disaster. As a result, for a generation or two of Prussian soldiers, the name “Jena-Auerstadt” evoked the pathetic spectacle of Prussian line infantry standing in close order stood in an open field , firing ineffective volleys at the stone walls that protected French sharpshooters.

In the vigorous French pursuit that followed the battle, the bulk of the Prussian army added disgrace to their defeat when scores officers surrendered perfectly defensible positions and thousands of individuals deserted the colors. One of the few bright spots in this catastrophe was the loyalty and skill of the Jäger. In small groups and even as individuals, large numbers of -fought their way through French controlled territory and reported for duty.

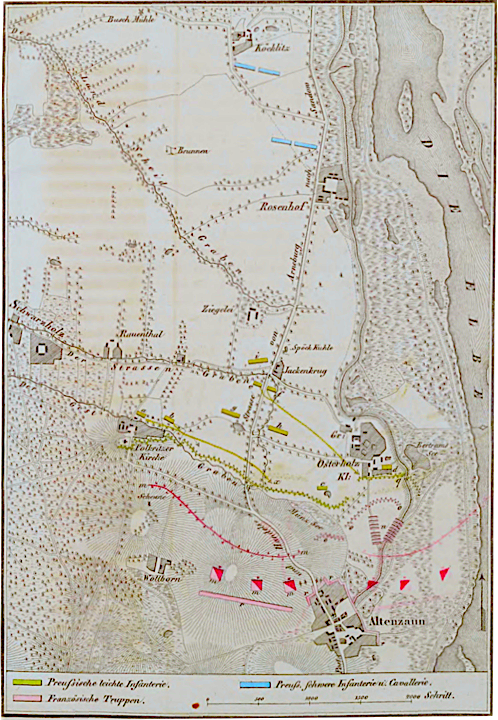

The Battle of Altenzaun (26 October, 1806) provides a first-class case study in how the squad and platoon tactics of the Jäger could be transformed into larger unit tactics with out losing their characteristics. Indeed, Altenzaun can be described as a large ambush, in which General Yorck von Wartenburg, former commanding officer of the Jäger Regiment, used six Jäger companies, three fusilier (musket armed light infantry) battalions, and two cannon to form a brigade level fire sack. As French skirmishers entered the trap the Jäger, making good use of the hilly, forested terrain, moved forward to tighten the noose. Thus, once the French came within rifle range, they found themselves fired on from three sides.

The French responded by reinforcing failure. True to their own tactical tradition, they followed their skirmish lines with columns. These columns fell prey to the two German cannon. And as the French formations were falling apart, the Prussians launched a counter-attack. At the end of the day, the Prussians had lost twenty men and succeeded in their mission of protecting the retreat, by ferry across the Elbe River, of the Duke of Weimar’s army. The French lost somewhere in the vicinity of 120 men and failed to achieve their mission of bagging large numbers of retreating Prussians as they waited to cross the river.

Sources: Peter Hofschröer, Prussian Light Infantry, 1792-1815 (London: Osprey, 1984); Curt Jany, Geschichte der Preußischen Armee vom 15. Jahrhundert bis 1914 (Osnabruck: Biblio Verlag, 1967); and Paul Pietsch, Die Formations und Uniformierungs-Geschichte des preußischen Heeres 1808-1914 (Hamburg: Verlag Helmut Gerhard Schulz, 1963)

For Further Reading:

.