Heavy Field Howitzers 1914-1915 (VIII)

Armies of the First World War

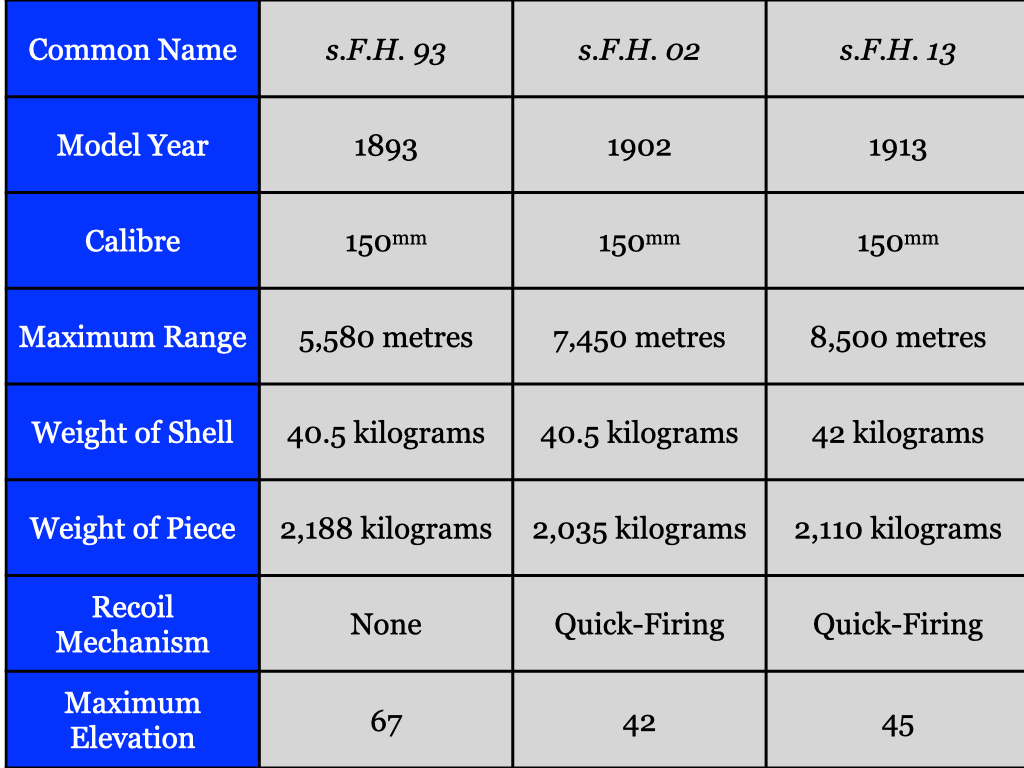

Like the British 6-inch howitzer, the 150mm howitzer adopted by the German Army in 1893 was initially designed to be used as both a light siege howitzer and a heavy field howitzer. At first, the former role was the primary one. That is to say, the German Army viewed the 150mm howitzer as a light siege howitzer that could, on occasion, be employed as a heavy field howitzer. Within a few years, however, German gunners reversed this relationship.

Thus, by 1897, while a few 150mm howitzers remained with the siege train and a good number could be found in fortresses, the lion’s share of the 150mm howitzers serving in the German Army had been formed into mobile batteries. In September of 1900, no less of a person than Kaiser Wilhelm II recognized this new reality by commanding that the weapon that had previously been known as the '15 centimeter howitzer' (15cm Haubitze) would henceforth be called the 'heavy field howitzer' (schwere Feldhaubitze.)1

Soon after the aforementioned change in nomenclature, the German armies began to take delivery of an improved model of heavy field howitzer. This new weapon featured a rudimentary on-carriage recoil-absorbing mechanism that, while not nearly as elegant as those of many contemporary field guns, greatly increased its rate of fire. (At the same time, the recoil-absorbing mechanism limited the ability of the new weapon elevate its muzzle in the manner of contemporary siege howitzers.)2 In 1913, the German Empire adopted yet another model of 150mm howitzer – a heavy field howitzer characterized by a much better recoil-absorbing mechanism, slightly longer range, and a slightly heavier shell. Only sixteen of these new howitzers were delivered to operational units before the outbreak of war in 1914.3

The following page provides links to all of the articles in this series:

Loebells Jahresberichte über die Veränderungen und Fortschritte im Militärwesen, 1900, p. 365.

The schwere Feldhaubitze of 1893 could raise its muzzle to an angle of 67°. That of 1902 could achieve a maximum elevation of 42°. The reason for this reduction was the inherent difficulty of designing a recoil-absorbing mechanism that worked equally well along a broad range of muzzle elevations.

The technical data for the s.F.H. 93 comes from Herbert Jäger, German Artillery in World War I, (Ramsbury: Crowood Press, 2001) p. 34. The figures for the s.F.H. 02 and s.F.H. 13 come from Hans Linnenkohl, Vom Einzelschuß zur Feuerwalze (Koblenz: Bernhard und Graefe Verlag, 1990) pp. 91-92 and 228 The abbreviation s.F.H. stood for schwere Feldhaubitze.