Heavy Field Howitzers 1914-1915 (VII)

Armies of the First World War

The British Army of the decade following the Second Boer War lacked a proper heavy field howitzer. One reason for this was its fondness for heavy field guns. The other was the ease with which the 6-inch (152mm) light siege howitzer it had adopted in 1896 could be modified for service in the field.

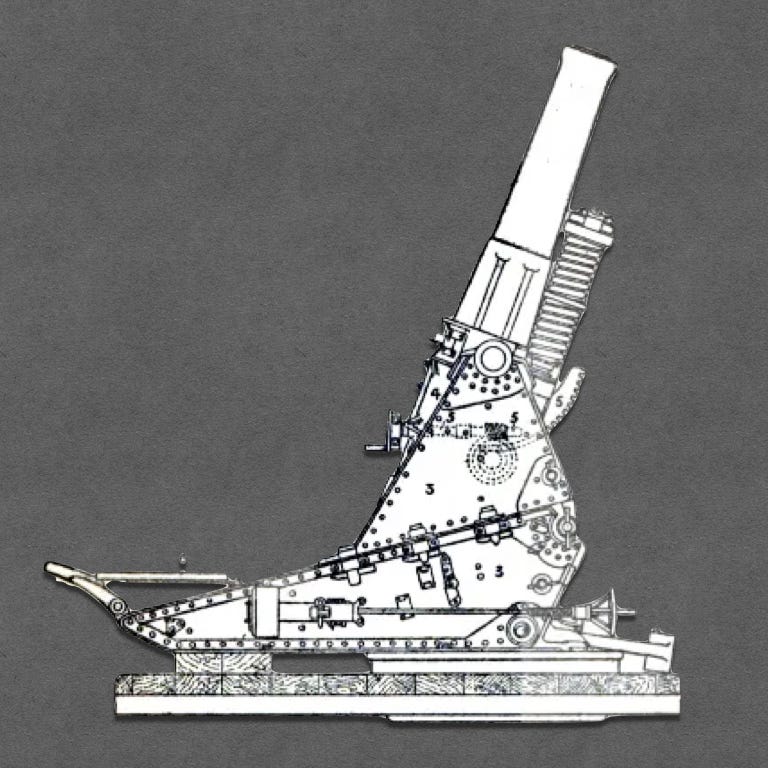

Imagined solely as a light siege howitzer, the original version of the 6-inch howitzer had been designed to fire a 122-pound (55-kilo) explosive shell that was much heavier than the projectiles delivered by other weapons of comparable caliber.1 By 1914, however, the British ordnance authorities had modified about half of the existing stock of eighty-five or so 6-inch howitzers in a way that permitted the use of shells that weighed but a hundred pounds (forty-five kilos.)2

While somewhat less destructive when dropped on top of the armored turrets of fortresses, the lighter shells traveled further than their heavier counterparts. They were also part of a family of munitions that included a shrapnel projectile. This, in the minds of Edwardian gunners, greatly enhanced the ability of the piece to engage the sort of targets they were likely to encounter while doing things other than bombarding fortresses.

The “double-hatting” of 6-inch howitzers was not without its costs. As the mobile version of the weapon lacked an effective on-carriage recoil absorbing mechanism, gunners employing the 6-inch howitzer in the field faced an unpleasant choice. If they took the time to place the piece on its siege carriage, they would benefit from the recoil-reducing devices that anchored the siege carriage to its wood-and-metal platform. If however, the gunners fired the piece from its traveling carriage, they could begin engaging targets immediately, but would have to manhandle the piece back into its firing position after each shot.

The dual-purpose 6-inch howitzers occupied a peculiar niche within the order of battle of the British Army. Rather than being assigned to units that belonged entirely to the field army or the siege train, they were issued to hybrid organizations known as “medium siege batteries.”

Like the heavy batteries of the day, medium siege batteries were provided with a full complement of horses, vehicles and drivers. These allowed the medium siege batteries to keep pace with an army on campaign. At the same time, medium siege batteries were provided with all of the gear needed to configure their 6-inch howitzers as light siege howitzers. In keeping with this Janus-faced function, the pre-war war establishments for the British Army listed medium siege batteries as “units which may be required with, but do not normally form part of, the Expeditionary Force.”3

The following page provides links to all of the articles in this series:

The characteristics of the explosive shells fired by the 6-inch howitzer can be found in War Office, Treatise on Ammunition (10th Edition) (London: HMSO, 1915), page 221.

An inventory of 6-inch howitzers is included with the Report of the Committee on Siege Artillery Material The National Archives (Kew) WO 33/701. This inventory, which dates from late September of 1914, does not include the sixteen 6-inch howitzers that were sent to the Western Front earlier that month.

War Office, War Establishments for 1907-1908 (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1907), pp. 163-66