Heavy Field Howitzers 1914-1915 (I)

Armies of the First World War

During the first year of the First World War, the German Army possessed many more heavy field howitzers than its enemies. At the battle of Gorlice-Tarnow (1 May 1915 through 3 May 1915), skillful employment of these artillery pieces allowed the Germans to achieve the Holy Grail of position warfare – an operationally significant penetration of a well-built defensive system.1 On the Western Front, German heavy field howitzers performed services that, while less spectacular than the bombardment at Gorlice-Tarnow, did much to strengthen the German armies fighting in France and Flanders. In particular, the widespread German employment of heavy field howitzers compensated for the deficiencies of the most numerous German artillery piece of the time and, in doing so, convinced decision-makers in the French and British armies to defer the acquisition of large numbers of heavy field howitzers of their own in order to devote resources to the fielding of heavy artillery pieces of a very different sort.

Guns and Howitzers

At the dawn of the 20th century, most of the artillery pieces employed by armies on land fell into the category of “guns.”2 Most easily identified by their long barrels, guns used relatively large propellant charges to impart a great deal of impetus to the shells they fired, thereby providing such projectiles with high speed, flat trajectories, and the ability to reach distant targets. Artillery pieces with substantially shorter barrels, which belonged to the category of “howitzers,” used much smaller propellant charges.3 These pushed projectiles along paths that were simultaneously slower, shorter, and rounder than those followed by shells fired from guns.4

Propellant Charges of British Artillery Pieces

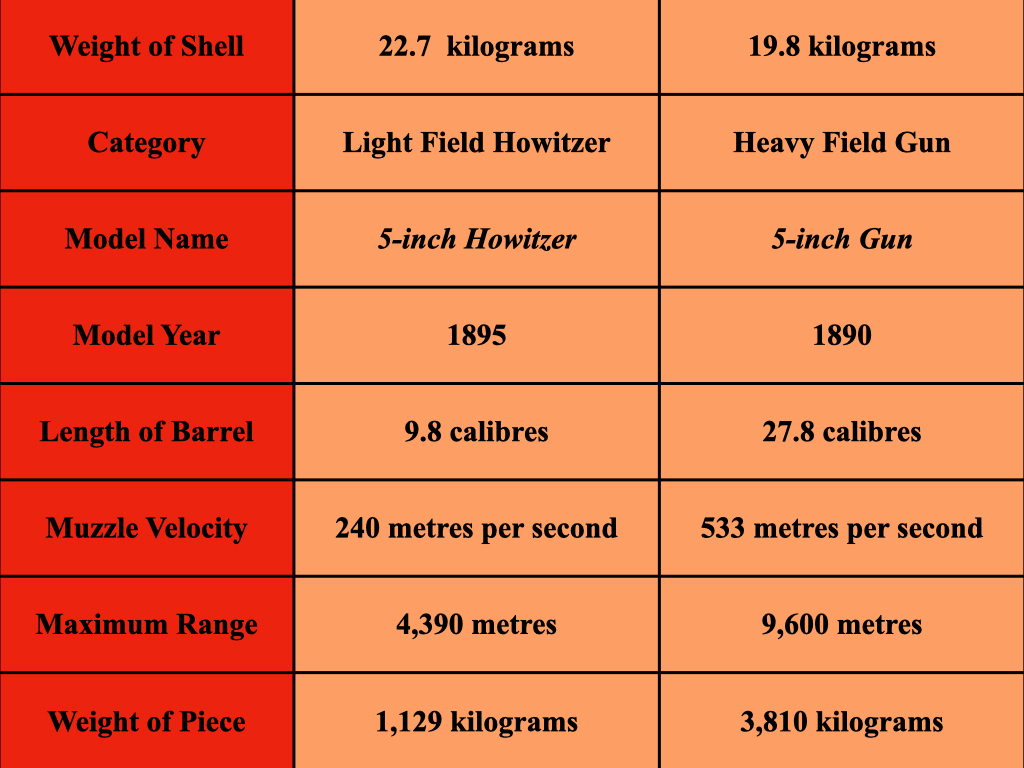

A longer barrel added more weight to an artillery piece than a shorter barrel. In addition to this, guns had larger chambers (to accommodate the larger propellant charges) than howitzers, as well as thicker barrels (to contain the stronger forces generated by the burning of the larger propellant charges.) Likewise, the carriage and recoil mechanism needed to support a longer, heavier barrel had to be both larger and stronger (and thus heavier) than corresponding elements of a piece provided with shorter, lighter barrel. In short, the effect of longer barrels upon the weight of artillery pieces was such that, all other things being equal, a gun of a given caliber weighed more than twice as much as a howitzer that fired a shell of similar size.5

French 120mm Artillery Pieces

British 5-inch (127mm) Artillery Pieces

For Further Reading:

The battle of Gorlice-Tarnow was a three-day struggle for a series of Russian-held positions in southern Poland. In taking these positions, the German Ninth Army tore a wide gap in the Russian line, thereby setting the stage for a series of successful operational maneuvers on the part of German and Austro-Hungarian formations. In addition to relieving pressure on the previously precarious Austro-Hungarian position in the Carpathian mountains, these maneuvers inflicted a series of stinging defeats upon Russian forces, deprived the Russian Empire of considerable territory, and greatly facilitated the task of defending both the Hapsburg heartland and East Prussia. For the definitive English-language work on this subject, see Richard L. DiNardo, Breakthrough: The Gorlice-Tarnow Campaign 1915 (Westport: Praeger 2010).

Like the word “cat,” “gun” has long served both as an informal name for a genus and a more precise designation of one of its component species. As might be imagined, this intersection of meanings has caused much in the way of misunderstanding. After 1930 or so, the widespread introduction of“gun-howitzers”, hybrid weapons called “howitzers” in the United States and “guns” elsewhere in the Anglosphere, added greatly to this confusion of terms.

While the definition of “gun” differed little from one army to another, the designations of short-barreled artillery pieces varied somewhat. Thus, in addition to employing the cognates of “howitzer” (obusier in French and Haubitze in German) to describe such weapons, French and German soldiers also used of terms, such as “short gun” (canon court) and “mortar” (Mörser), left over from the middle years of the nineteenth century.

Longer barrels were associated with larger propellant charges because larger propellant charges needed more time to burn. If a larger propelling charge were used with a shorter barrel, unconsumed propellant would remain in the piece after the shell had left the tube. As this continued to burn, it would result in a great deal of flash and noise. The shell, however, would acquire little in the way of additional propulsive power. For a clear explanation of this phenomenon, see Henry Arthur Bethel, Modern Guns And Gunnery, 1910: A Practical Manual for Officers of the Horse, Field And Mountain Artillery (Woolwich: Cattermole, 1910), pp. 1 and 2. For the source of the information presented in the chart marked Propellant Charges of British Artillery Pieces see War Office, Treatise on Ammunition, (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1915), pp. 81, 84, 100, and 102.

In some instances, such as that of explosive shells for the 6-inch (152mm) pieces in the service of the British Empire, howitzers used shells with thinner walls (and thus larger payloads) than the shells designed for guns of the same caliber. In others, such as that of shrapnel shells for British 6-inch pieces, both guns and howitzers of a given caliber used the identical projectiles. Treatise on Ammunition (1915), pp. 141, 220, and 221. Technical data for the French 120mm artillery pieces come from Jules Challéat, Histoire Technique de l’Artillerie de Terre en France Pendant un Siècle, Tome II (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1935), p. 169. Technical data for the British 5-inch pieces come from Ian Hogg and L.F. Thurston, British Artillery Weapons and Ammunition, 1914-1918, (London: Ian Allen, 1972), pp. 124-25, 128-29, and 235.