In the years leading up to 1914, the cavalry regiments of the German Empire produced, in proportion to their peacetime strength, fewer reservists than units of most other arms. One reason for this was the relatively high ratio of officers and non-commissioned officers to troopers. The second was fact that, at a time when most German conscripts served but two years in uniform, men selected for peacetime service with cavalry regiments were obliged to spent a minimum of three years “with the colors.” The third reason for the shortage of reservists who had been trained as cavalrymen stemmed from the greater tendency of young German horse soldiers to re-enlist after completing their initial terms of active service.

Because of this shortage of reservists, the depots of cavalry regiments produced, in proportion to their numbers, far fewer second-line (Reserve, Landwehr, and mobile Ersatz) units than the depots of infantry regiments. That is, in the course of mobilization, the depots of the 110 cavalry regiments of the German armies mobilized 452 active squadrons (chiefly composed of soldiers already in uniform) and 152 second-line squadrons (mostly made up men who had been out of uniform for somewhere between nine months and seventeen years.) In the same period, the depots of 217 infantry regiments produced 218 active infantry regiments and 217 second-line infantry regiments.1

Once the units mobilized during the first week or so of August 1914 took the field, the depots left at home began to train the men in their charge. In the case of cavalry units, this task was greatly complicated by the amount of time needed to turn a civilian into a competent horse soldier. First, the recruit needed to learn how to ride spirited horses in challenging circumstances.2 This done, the apprentice horse soldier had to master several weapons (saber, lance, and carbine), learn to care for his mount, and become familiar with a wide variety of duties in the field. In time of peace, learning these skills was seen as the work of nine or ten months. Acquiring them in the ten weeks or so that were available for the training of the units of the war volunteer divisions was thus out of the question.3

Under such conditions, the War Ministry had two options for providing new divisions with cavalry. The first was to create new squadrons of sub-standard horsemen. Such units would be capable of providing mounted messengers and patrolling rear areas, but little else. The second was to transfer fully trained squadrons from older formations to new ones.

The first approach provided poorly trained cavalry detachments to divisions of the First and Second Series.4 The second method found fully capable cavalry squadrons for divisions of the Third and Fourth Series. (One such squadron was assigned to each division of the Third Series. Two such units were given to each of the Fourth Series divisions.)5

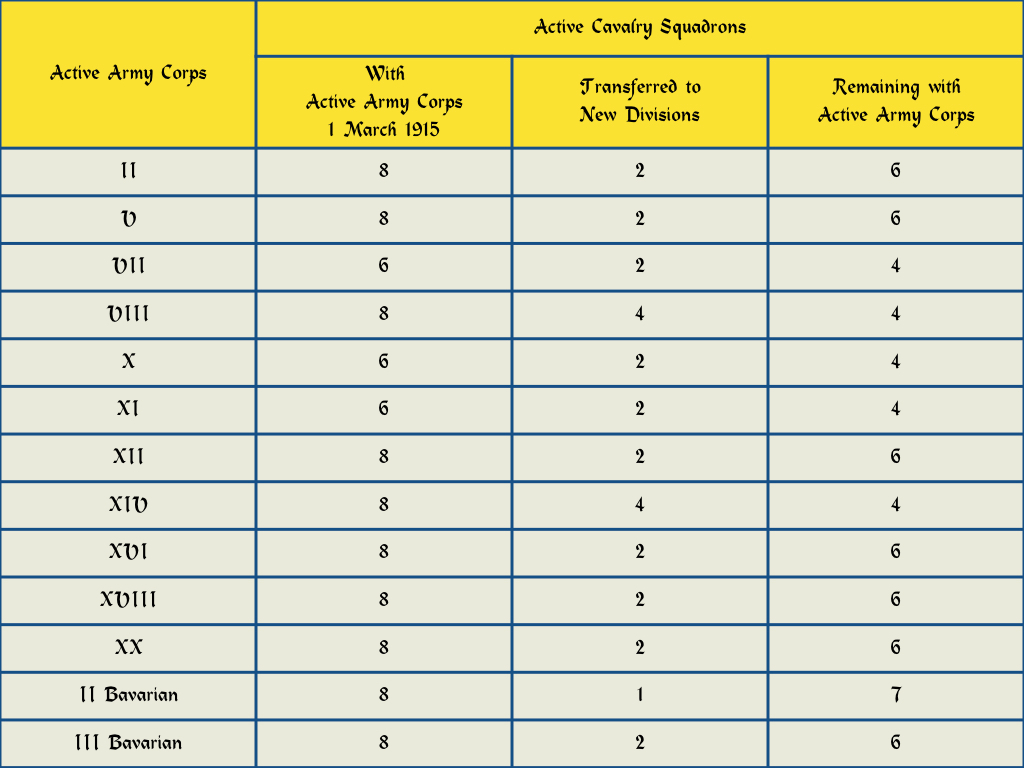

Without exception, the squadrons transferred to divisions of the Third and Fourth Series had been serving with infantry divisions of active army corps. (The cavalry regiments of cavalry divisions were thus able to retain all of their squadrons.) This was done in such a way as to ensure that each army corps that gave up cavalry to the new divisions retained a minimum of four squadrons.

In the course of the transfer of thirty-two squadrons from active army corps to divisions of the Third and Fourth Series, only two squadrons moved from the Western Front to the Eastern Front. (These were the two squadrons assigned to the 11th Bavarian Division, a Fourth-Series formation that was raised in the East from elements that, for the most part, had been serving with divisions on the Western Front.) The other thirty squadrons involved in this reallocation moved from one division to another without switching fronts.

Cron, Imperial German Army, pages 114 and 128. (The “extra” active infantry regiment, the Lehr Infanterie Regiment, was assembled at mobilization from the Lehr Infanterie Bataillon and other peacetime training units.)

In the autumn of 1914, a scheme to reduce the time needed to train would-be cavalrymen by recruiting men who had learned how to ride in civilian life yielded a single squadron. Telegram of General von Lynecker, Chief of the Military Cabinet, to the Prussian War Ministry, dated 19 October 1914. NARA, M932, Roll 3.

H.C. von Zobeltitz, ed., Das Alte Heer, Erinnerungen an die Dienstzeit bei Allen Waffen, (Berlin: Heinrich Beenken, 1932), pages 26-7 and 92-4. See also “Lanze oder Säbel,” Militärwochenblatt, 1911, Nr. 30, pages 667-9.

Kriegsministerium, MJ Nr. 4029/14.A.1. Geheim., dated 19 August 1914, Gesichtspunkte für die Ausbildung der neu zu bildenden Reservetruppen, Bundesarchiv Freiburg, Kriegsgeschichtlichen Forschungsamt files, (RH 61) W10 50755. The author would like to thank Dr. Robert Foley for providing a copy of this document.

Organizational diagrams appended to Kriegsministerium MJ Nr. 5463/15 A 1, dated 21 March 1915 and Kriegsministerium MJ Nr. 3844/15 A 1, dated 21 March 1915, dated 1 March 1915, NARA, M932, Roll 3.