This article continues a series that begins with …

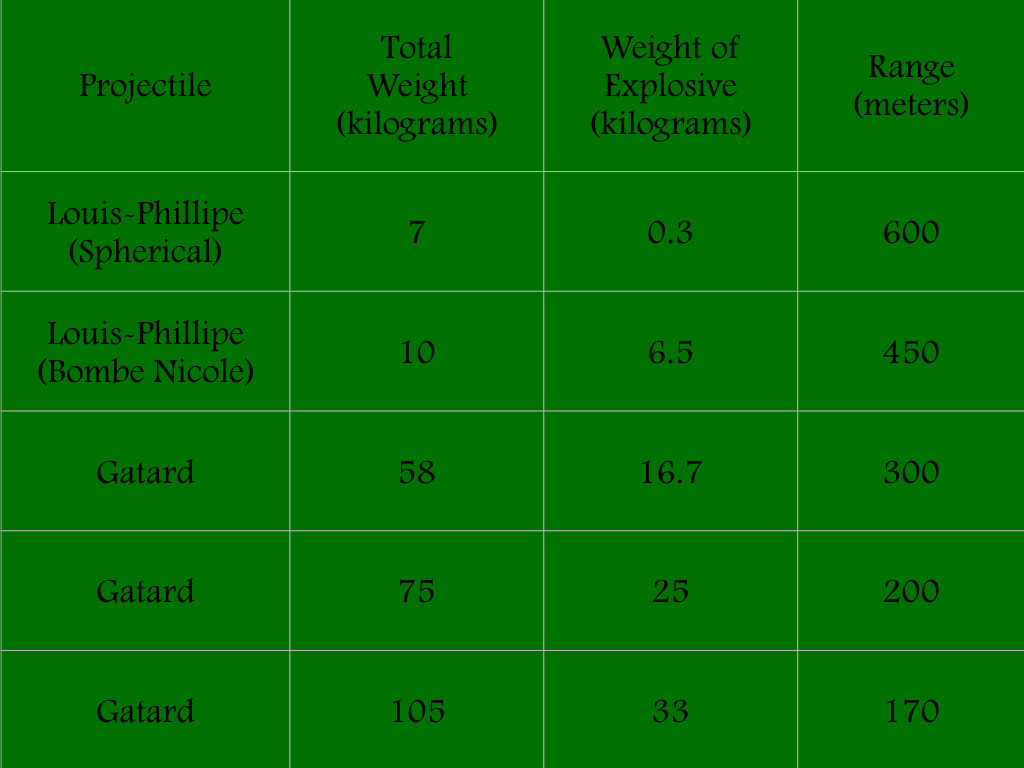

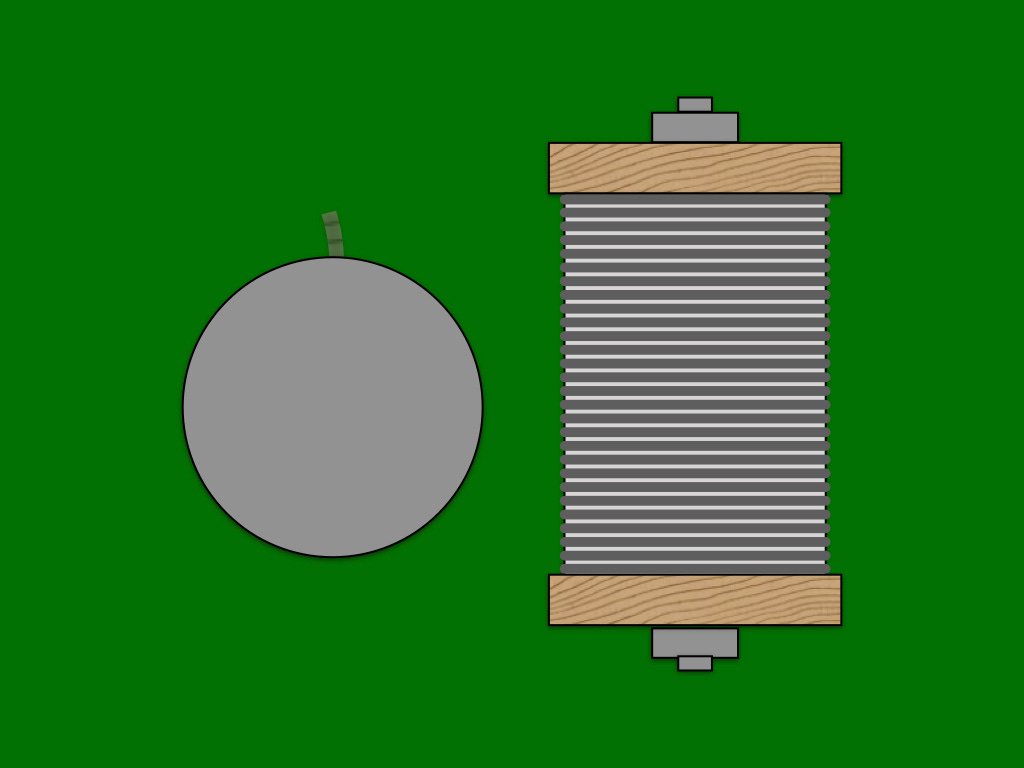

The Louis Philipe mortars brought out of retirement soon after the onset of position warfare had been designed to use round bombs of a highly traditional type. (Menno van Coehoorn, please call your answering service.) Filled with either old-school black powder or new-fangled high explosive, these cast iron spheres could travel as far as six hundred meters. When, however, they exploded at (or, more frequently, near) the end of their journeys, they often wrought more insult than injury.

In the hope of doing more damage to the Germans on the other side of “no man’s land,” the French trench mortar enthusiasts soon improvised more powerful projectiles. The most successful of these, known as the bombe Nicole, consisted of commercial explosive charges formed, with the aid of wood, wire, and sheet metal, into cylinders. These devices yielded more satisfying explosions than the original ammunition, albeit at a cost of a modest reduction in range.

The charges delivered by the Gatard mine-thrower [lance-mines Gatard] were substantially larger than those, both old and new, tossed by the venerable Louis Philippe. Nonetheless, as the casing that held the explosive charge was made of cast iron, the price of such explosive largesse was a combination of size, weight, and shape that put severe limits on range. (Towards the end of the short life of the Gatard mortar, a forty-kilogram cast-steel projectile capable of traveling four-hundred and fifty meters made its appearance. By that time, however, bombs of comparable payload, and much greater range, were being fired from competing devices.)

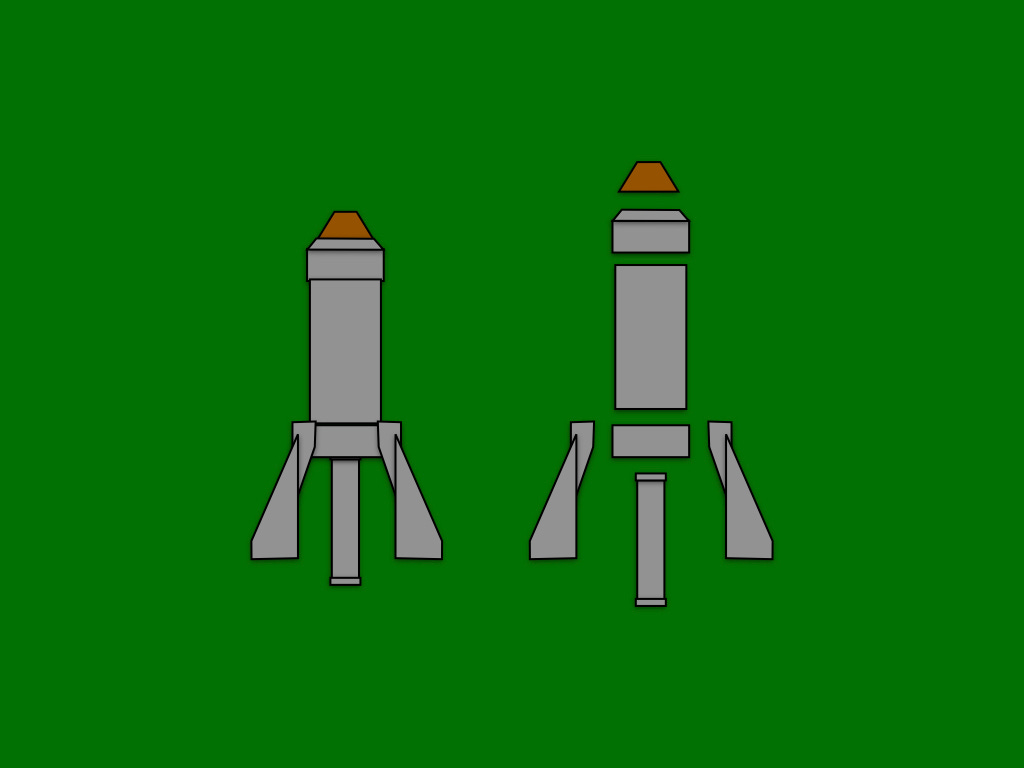

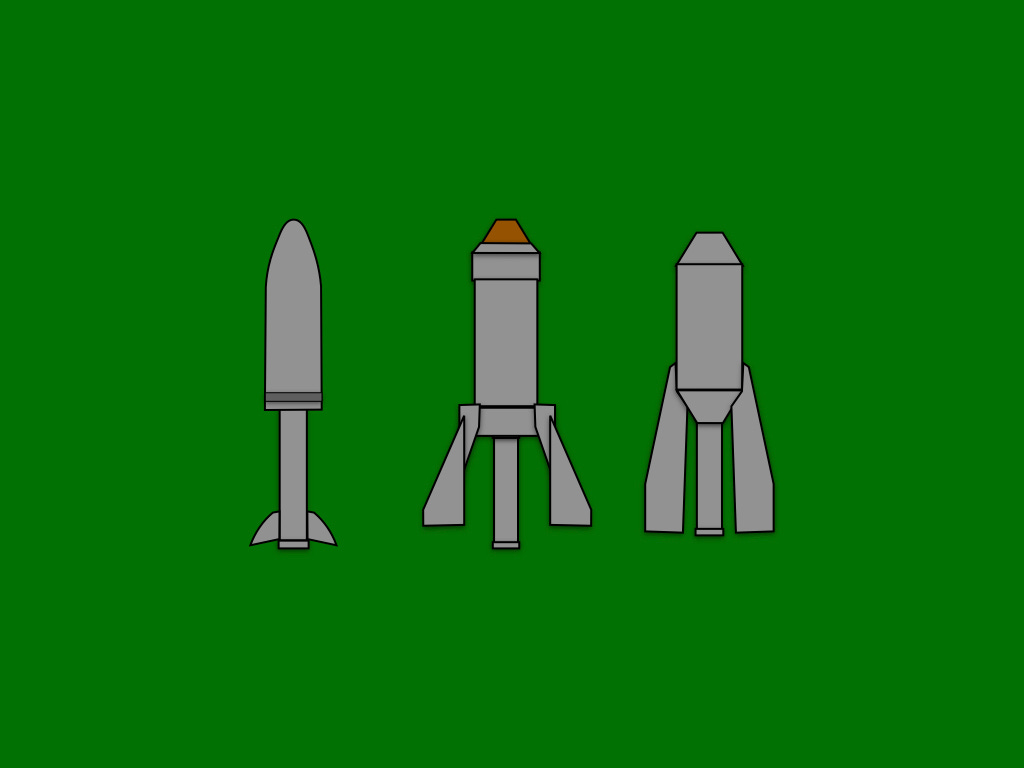

The first projectile used with the 58 T of Émile Duchêne was a 120mm shell, designed originally for the Model 1878 de Bange heavy gun of that caliber, that had been fitted with a solid metal rod and a small pair of fins. It was not long, however, before the migration to the front of large numbers de Bange pieces deprived Duchêne of his ability to obtain 120mm shells.

The next projectile the Duchêne produced for the 58 T was a sixteen kilogram bomb designed to be assembled shortly before firing. This “separate elements bomb” (bombe à éléments séparés) was made largely out of sheet metal. This allowed it to carry more in the way of explosive material than projectiles in which the payload was encased in cast iron.

Notwithstanding its appeal to the mentality that, later in the twentieth century, would give the world such things as Lego and IKEA, the “separate elements bomb” did not last long before giving way to a sturdier projectile of the same weight. This second sixteen-kilogram bomb, which was characterized by somewhat larger fins that had been soldered to the body, enjoyed enduring success. Indeed, it became so closely associated with the trench mortar batteries that it was soon adopted as the badge of the crapouilloteurs.

Sources: This post is based upon information found in the textbooks used in French military schools in the years between 1917 and 1935. These can be found by going to the digital collection of the French National Library and searching on the phrase “artillerie de tranchée.”