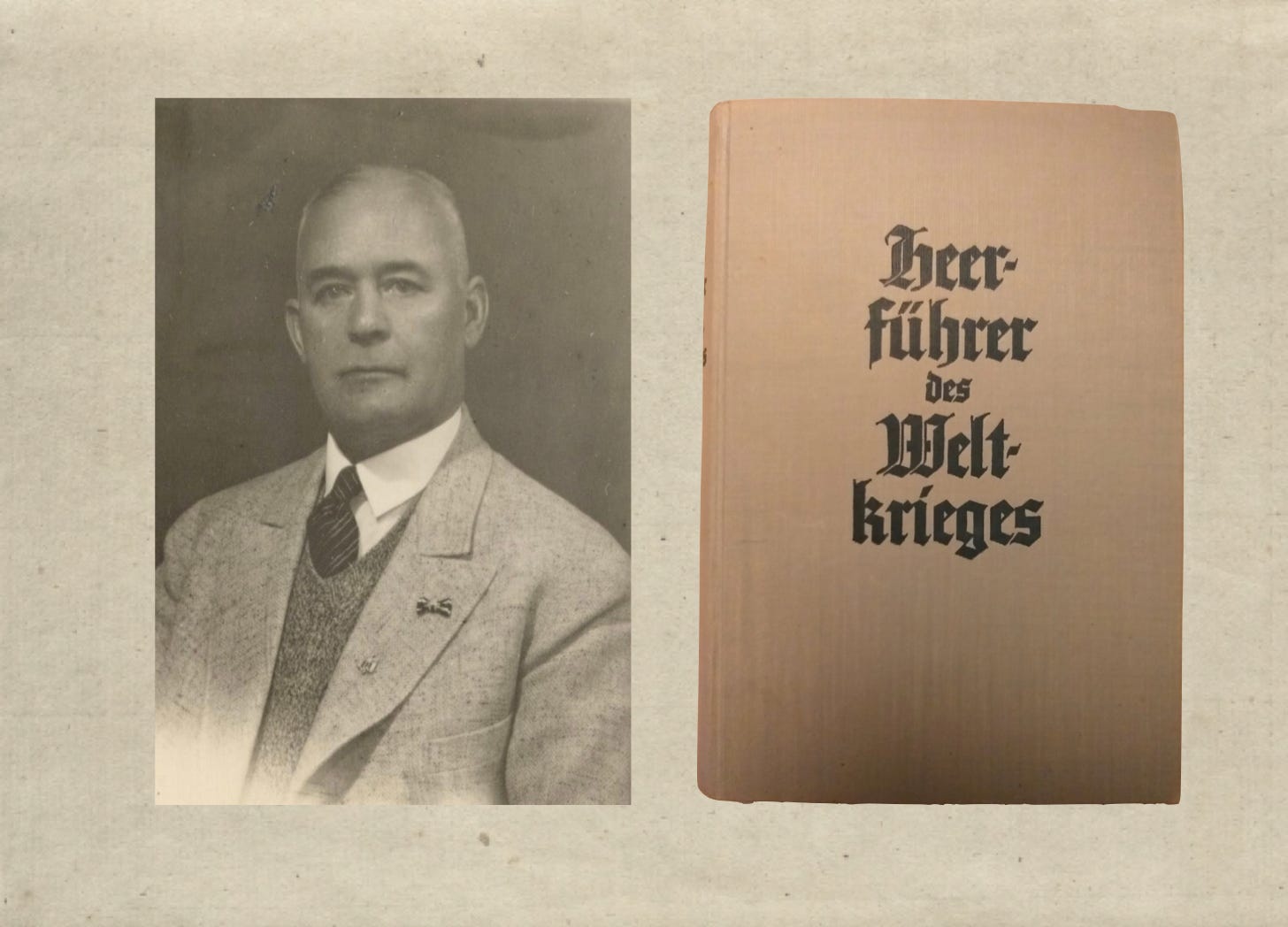

In the issue of that magazine dated April, 1939 Wissen und Wehr (Knowledge and Defense) published a substantial reply to the three articles articles that Georg Wetzell had written in response to the introduction that Wolfgang Foerster wrote for his book Heerführer des Weltkrieges (Military Commanders of the World War.) The sub-series begun with this post presents a translation of this article made by Frederick W. Morton in 1939 and revised, with reference to the German original, by Your Humble Servant.

For links to translations of the articles written by General Wetzell and, when they appear, the other parts of Lieutenant Colonel Foerster’s article, please see

Wolfgang Foerster

The Picture of the Modern Military Commander:

A Word of Defense and Explanation

(Start)

In a series of articles appearing in the Militärwochenblatt (Military Weekly) General Wetzell has taken exception to statements contained in my introduction to Heerfuhrer des Weltkrieges, a collection of biographies recently published by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Wehrpolitik und Wehrwissenschaften (German Society for Military Policy and Science). General Wetzell observes that his personal experiences in war and his study of military science do not permit him to agree with some of my views. Inasmuch as these views deal with one of the most important, though not the central problem of modern conduct of war, I believe it desirable and helpful to clarify matters objectively by examining the questions which Wetzell and I have treated. Of course, we must bear in mind that this discussion can deal only with certain features (and not with my entire outline) of the modern military commander.

In my study, I start with the viewpoint that the historical evolution of the military commander reveals epochs. While I do not regard these distinctions as complete and exclusive, I recognize them largely in the revolutionary effect of the progress made in the field of technique: the introduction of new and more powerful weapons, the improvement of traffic and communication facilities, the organic combination of new means of warfare. I date the 'modern period of military commander' back to the departure of Napoleon from the state of military history, basing my contentions on the fact that the wealth of technical innovations which were introduced in the post-Napoleonic era had a tremendous and well-nigh revolutionary effect upon the conditions and possibilities of the military commander. It is safe to say, therefore, that the era of the modern military commander was initiated by a technical revolution.

Wetzell argues, however, that the modern period of military command began even earlier, that is, with Napoleon as the creator of modern warfare on a large scale. He goes on to say that the development of technique after Napoleon was not revolutionary, but took the forms of a very gradual 'evolution', I do not care to debate the meaning of the terms 'revolution' and 'evolution'. Yet this much is certain: the extraordinary progress made in the field of technique in the post-Napoleonic era marks an important step in the course of world history. With the twenties and thirties of the 19th century, there begins an 'era of inventions'.

The fact that the roots of that era reach far back does not alter the fact that a mass of innovations appeared suddenly and had a fundamental influence upon life in peace and war. The rapid succession of technical developments (rail road, telegraph, improved and new fire arms), which originated at that time, altered the conditions and possibilities of military command so considerably that we may justly speak of a 'new period'. In this connection, I wish to refer to the testimony of that military commander who first recognized and took advantage of this change, Moltke himself. In his Aus den Verordnungen für die höheren Truppenführer vom 24. Juni 1869 (From the Regulations for the Higher Formation Commanders of 24 June 1869), he expressly states, as mentioned in my introduction:1

The progress made in the field of technology, the improvements made in communications, the introduction of new arms, in short, the complete change in conditions frequently seem to render it impossible in present times to use means that made for victory in former times and even seem to upset the rules laid down by the greatest military leaders.Moltke repeats this statement in his Instruktionen für die höheren Truppenführer (Instructions for Higher Formation Commanders) of 1885, thereby proving, beyond a doubt, that he attached a lasting meaning to it.2 Wetzell admits that Moltke’s statement was 'correct in itself'. However, he seeks to minimize its importance by remarking that Moltke, in practice, 'followed the sense of the principles established by Napoleon'. These words disprove nothing; for Moltke, in making his statement, certainly had no intention of refusing outright all rules established by the great generals of the past. Moltke merely speaks of those rules as being 'frequently impossible to use in present times'. From this I drew the conclusion that 'the lessons, that is, the purely military strategic logic of former times could apply only with certain reservations'.

To be continued …

For links other parts of this series, please see:

Helmuth von Moltke ‘Aus den Verordnungen für die höheren Truppenführer vom 24. Juni 1869’ (‘From the Instructions for the Higher Formation Commanders’) in Moltkes Taktisch-Stragegische Aufsätze aus den Jahren 1857 bis 1871 (Moltke’s Tactical-Strategic Essays from the Years 1857 to 1871) (Berlin: E.S. Mittler, 1900) pages 167-215. For a translation into English, see Daniel Hughes, editor, and Harry Bell, translator ‘Instructions for Large Unit Commanders’, in Daniel Hughes, editor, Moltke on the Art of War (Novato: Presidio Press, 1993) pages 171-224 (The first link will take you to the Military Learning Library. Subsequent links will take you to the Internet Archive.)

Alas, I have yet to find a copy of the Instructions for the Higher Formation Commanders of 1885.

An evolution that continues.

We have more communication than ever before, complete with the electromagnetic spectrum becoming crowded- perhaps there’s a balance of security to be found in “clutter” and chatter.

Camouflage of sorts.

In a wall of sound a rhythm can be underlaid, camouflage in cacophony.

In weapons we move from the bigger the bang the better to the smaller and more precise indeed mere kinetic mass at hypersonic speeds replaces nuclear weapons, as does new chemistry with hydrogen weapons of magnesium hydride explosive that burnt at 1000 Centigrade.

As we are still hopefully on the downward slope of “total war” in terms of ideology and religion* as well as national struggles of entire peoples as anthills engaged in wars of annihilation all this is to the greater good of man.

No idealist here- a cynical war for resources fought by mercenaries under no illusions is far less destructive than the Nordic, Varangarian and Wagnerian dramas we just emerged from a few decades ago.

“Reduce every conflict to resource conflict then fight and settle on those terms “~ to keep the butchers bill and blood vengeance to a minimum.

My own humble contribution to humanity, sincerely- TLW

Cynical Humanist