For many years, the US Army and Marine Corps subjected all candidates for initial commissions (save those who had graduated from West Point or Annapolis) to rigorous examinations. While these tests often included a military component, these served chiefly to ensure that the would-be lieutenant possessed a sound general education.

During the First World War, the need to find junior officers for the large number of units being formed led to the practice of exempting holders of college degrees from these tests. Such certificates, senior officers argued, guaranteed that those who had earned them were as literate, numerate, and well-informed as those who had passed muster with the examiners.

In the years that followed, this wartime pis aller displaced all systematic attempts to establish the intellectual qualifications of a would-be junior officer. Thus, by the middle years of the twentieth century, humorists in the ranks could, with considerable justice, describe freshly-minted second-lieutenants as “privates with college degrees."

During the Second World War, the Korean War, and America’s involvement in the long war in Indochina, the Army and Marine Corps commissioned a number of men who lacked the otherwise obligatory sheepskin. All concerned, however, saw such appointments as temporary measures. Thus, once the emergency in question had ended, the Army and Marine Corps sent the most promising of the degree-free officers to college and their less impressive comrades back to Civvie Street.

In the last sixty years or so, the close connection between bachelors degrees and butter bars survived both a massive increase in college enrollment and the concomitant dilution of academic standards. In the years to come, however, the relationship may well run aground on rocks and shoals of a different sort.

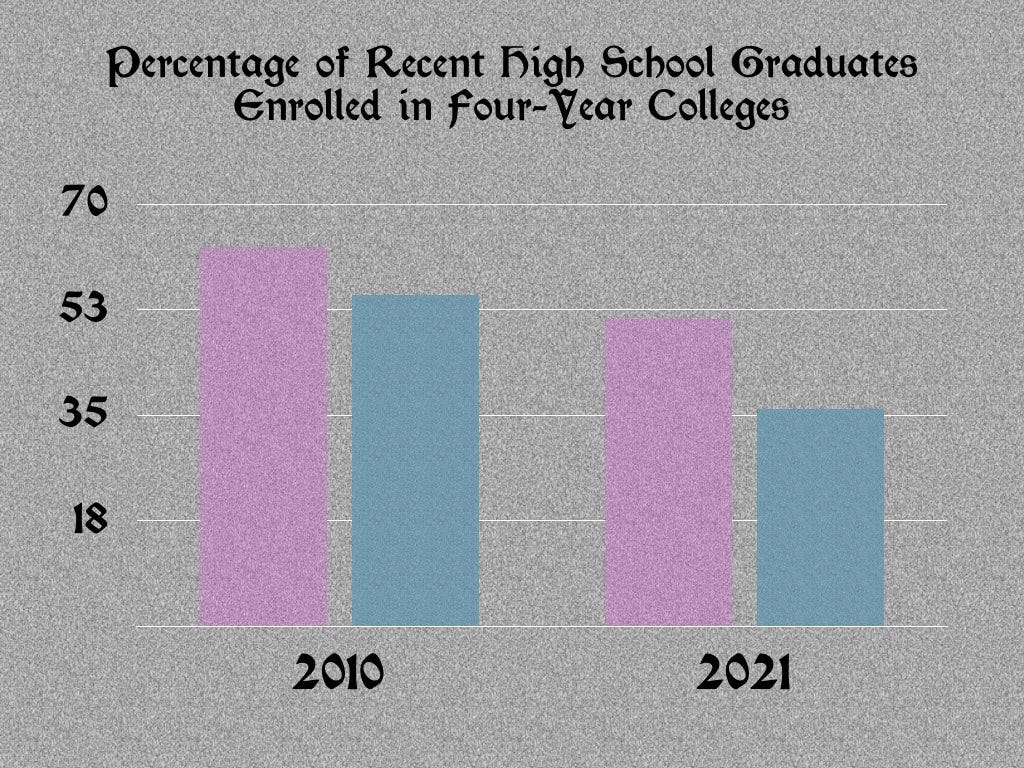

The National Center for Educational Statistics tells us that recent high-school graduates of the female persuasion are much more likely than their male classmates to enroll in a four-year college.1 Moreover, while the percentages of people of both sexes going straight from high school to a full-fat undergraduate program has dropped, men have been leading that exodus.

If this trend continues, we may soon see the pursuit of a bachelors degree go the way of horseback riding, school teaching, and tap dancing. In the short term, the resulting bumper crop of clever young men looking for something to do will create an opportunity for the America’s armed services. That is, if our generals are wise, they will make the prospect of four years in uniform attractive to what the Scots used to call “lads o’ parts.” In the long term, however, such men will seek advancement, and, lacking bachelors degrees, will have to find it somewhere else.

The solution to this conundrum lies in the revival of the commissioning examination. This would send a powerful message to ambitious young men who, having realized that college has become an extended (if poorly catered) debutante ball, are looking for other ways to put their talents to use. “Enlist now,” the recruiting sergeant will be able to say, “keep your nose clean, and spend your free time with serious books and quality podcasts. Do those things, and, before you know it, you’ll be an officer. ”

›

“Immediate College Enrollment Rate” National Center for Educational Statistics (May 2023)

Bruce, a great idea and one that should be implemented regardless of educational credentials. It won't happen though. Standardized testing, which ostensibly provides a leveling standard to compensate for pervasive grade inflation or to call out folks swimming in weak (or very strong) academic gene pools, is being pushed aside in college admissions slowly but consistently. The odds of the DOD implementing something like this is nil. Hell, the Army can’t even implement its own physical fitness test (the most basic and benign functional standard of the profession of arms) without severe political scrutiny and interference because it is not "fair". Huntington is dead, both in reality (RIP) and now metaphorically (double RIP).

The Marine Corps has had a reasonably strong tradition of enlisted Marines through various routes becoming commissioned officers. “Mustangs” brought a unique and important perspective to the units in I served in, and at OCS the Mustangs that were going through were pretty helpful, “here dumbass, you shine your brass faster this way...” though basically they considered it all a big pain in the neck and an addition/enhancement to the harassment package, to which they brought their own brand of gallows humor, which was always quite welcomed. “What’s the difference between the Boy Scouts and the Marine Corps? The Boy Scouts have adult leadership.”

That said, something seems to have worked over time. However, in these unsettled times some introspection and taking stock of the recruitment, selection, training and so forth prior to anyone being allowed to be commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the United States Marine Corps, is in order. How do we recruit, select, train and mentor the commissioned officer corps? It seems self evident that standards not change and if for some reason the idea that we find intellectual giants in code writing in Silicon Valley and put gold oak leaves on their collars without having the pleasure of a visit to “The Quigley!”, ought to be reason enough to call that a very bad idea for helping recruit, select and ultimately commission a Marine Corps Officer. Speaking of Mustangs Lieutenant William Quigley was a tactics instructor at OCS when he was charged with coming up with a “combat course” to challenge the “Candidates” physically and mentally and simulate as much stress as possible. No matter the MOS almost all officers in the Corps have the shared experience of The Quigley.

It seems very logical to look inward and be sure we are giving the best possible set of opportunities to the enlisted ranks to become commissioned officers, and at this point whether a university sheep skin is a valid metric for selection might be worth a hard look and stern review, as well.