In the issue of that magazine dated April, 1939 Wissen und Wehr (Knowledge and Defense) published a substantial reply to the three articles articles that Georg Wetzell had written in response to the introduction that Wolfgang Foerster wrote for his book Heerführer des Weltkrieges (Military Commanders of the World War.) The sub-series continued with this post presents a translation of this article made by Frederick W. Morton in 1939 and revised, with reference to the German original, by Your Humble Servant.

For the first three posts in this sub-series, please see …

For links to translations of the articles written by General Wetzell and, when they appear, the other parts of Lieutenant Colonel Foerster’s article, please see

Wolfgang Foerster

The Picture of the Modern Military Commander:

A Word of Defense and Explanation

(Continued)

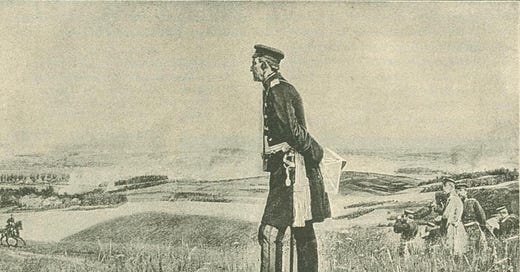

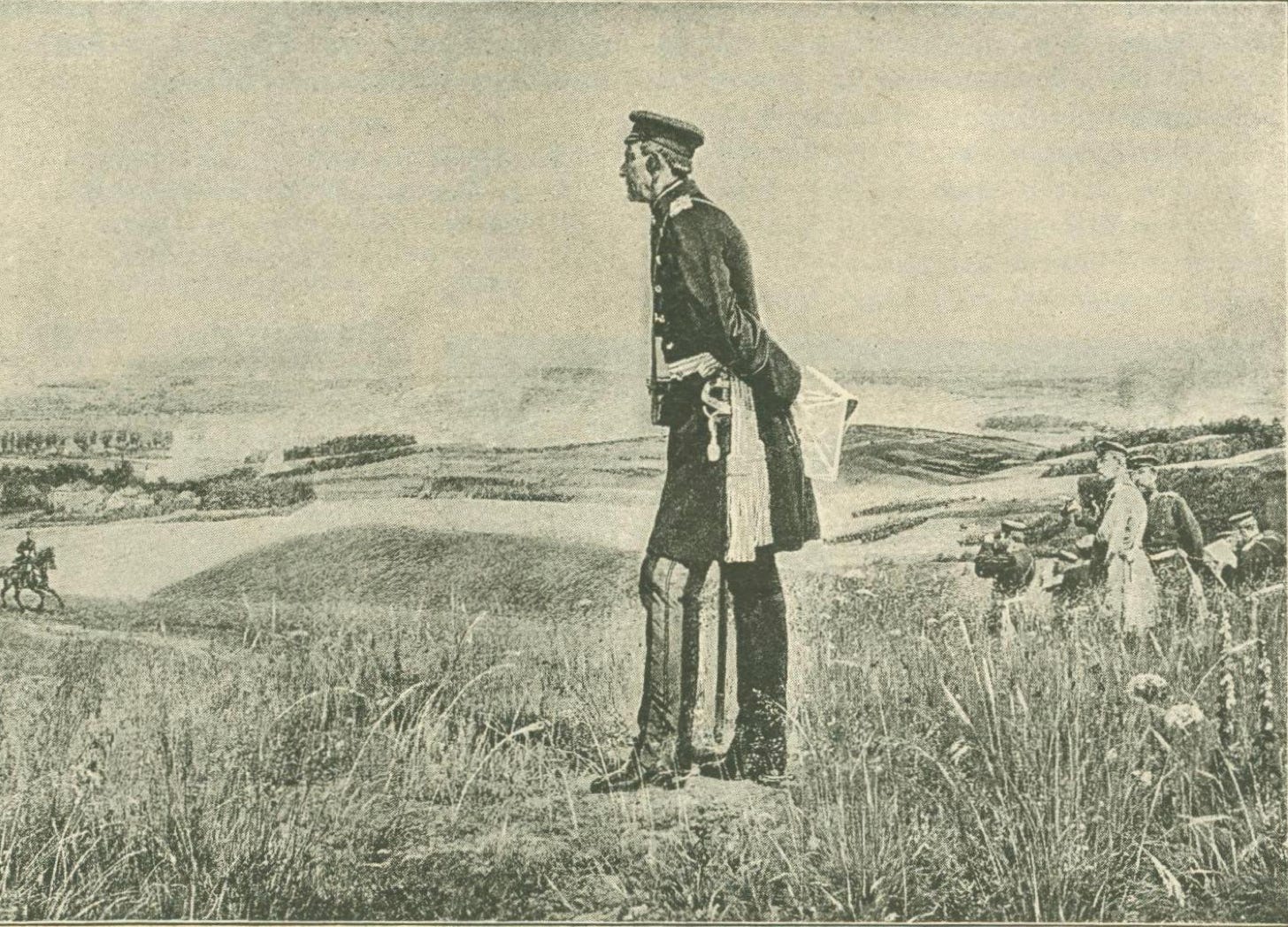

As regards the conduct of the operations of Napoleon and Moltke, I cited Napoleon and Frederick the Great as typical figures for the illustration of ‘the military commander who directs the battle from a suitable observation post’ and, with reference to Napoleon, quoted his principle: On s’engage partout, puis on voit. [‘I make contact everywhere and then I see.’]

Wetzell says that this by no means completes the ‘picture of the military leadership of Napoleon’. True enough, but my mention of the general’s hill and quotation of the principle of command was intended solely to emphasize the personal and direct conduct of the operations which characterized the actions of Napoleon. I cannot imagine that Wetzell thinks differently about this matter; on the other hand, I fully concur with all of Wetzell’s remarks about the method which Napoleon used in the conduct of his operations. The only difference is that his remarks miss the meaning of my statements.

However, with regard to Moltke’s conduct of operations, our views differ widely. I have this to say about the modern military commander:

The principal work of the commander in chief is finished as soon as the forces are engaged in battle, in the sense which Moltke considers ideal. Although the commander does not retire completely from the direction of the operation itself, his subsequent efforts will be small in comparison with his previous function as bearer of the central will. The battle is and remains the essence of his will, but the main part of his activities precedes the battle. Thus I summarized the intentions and actions of Moltke, before and at Königgrätz, by stating this his decisive act as commander in chief consisted in his ordering the Crown Prince of Prussia, during the night from July 2 to 3, to march to the battlefield. The appearance of Moltke, in the company of his king, on the scene of battle the following day, as at Gravelotte and Sedan in 1870, was due to a natural concession to the traditional picture of the past and to a technical error which has been corrected in the meantime. For the means of communication were still in a state of imperfection.

Wetzell objects to this. He writes:

There certainly must have been reasons other than the traditional picture which caused Field Marshal Moltke to be invariably near the decisive point of battle, indeed, to conduct the operations of issuing direct orders, as in the Battles of Königgrätz, Gravelotte and Sedan. He knew military history and, especially in 1855, he had gathered ample experiences prior to the Battle of Königgrätz. That was the reason why Moltke did not remain far in the rear at a desk, but took up a position far enough forward to enable him to observe matters and personally to take a decisive hand wherever required. Moltke is not only the man who studies the preceding operations (Schlachtendenker), but he is also - and here is where his real greatness lies - the director of the (Schlachtenlenker): Königgrätz, Metz, Sedan. The question of the ‘desk general’ I shall discuss later. Our immediate problem deals only with Moltke’s activity as the director of battles at Königgrätz, Metz, and Sedan. I maintain that on all three occasions he actually was more or less an observer - and rightly so.

In the Battle of Königgrätz, Moltke reassured his worried king around the noon hour, by which time it had been unnecessary for Moltke to issue a single order:

Today Your Majesty is winning not only this battle, but the entire campaign as well.This goes to show how confident Moltke was of the effectiveness of his previous labors as bearer of the strategic central will. As regards his intervention in the conduct of the operations of Prince Frederic Carl and the commitment to action of the First Army reserve at noon, Moltke himself said later:

The Chief of Staff had ridden forward to the woods of Sadowa, where he did not belong; yet he had no knowledge of the early employment of the army reserve on July 3, 1866, prior to its commitment to action. All he could do was to prevent Manstein’s division from breaking out of the woods as ordered. The only written directive issued by Moltke in the course of the battle was that addressed to the Army of the Elbe, wherein he called attention to the urgent need of an advance. This order failed to have the intended effect. The failure of the High Command to order an effective pursuit on the eve of the battle is explained in a historical monograph of the Great General Staff; there it is stated that ‘even Moltke did not fully realize the extent of the victory at the conclusion of the battle’.

As for the battles around Metz, August 1870, Moltke did not witness the first two battles on August 14 and 16. Wetzell says that Moltke, ‘on August 15, in true Napoleonic fashion, rushed to the battlefield of Colombey’. These words can easily be misinterpreted, for the battle had taken place the day before. Wetzell fittingly acclaims the army directive of noon, August 17, as ‘classic’. This directive provided for the advance of the Second Army in echelons from the left flank.

However, despite Wetzell’s claim, Moltke did not issue this directive after he had ‘clarified the situation’ of the Second Army; on the contrary, he was completely in the dark about the hostile disposition, having been unable to throw any light on the situation despite his presence on the battlefield the foregone day and notwithstanding exhaustive discussions with his subordinate commanders. Here again, it is the work of the military commander prior to the decisive battle which made victory possible and assured the success of the operations. Alongside this preparatory work, the activity of the commander in the battle of August 18 (Gravelotte - St. Privat) is of secondary importance.

According to the careful research and estimate of the General Staff, the High Command on that day ‘played the role of the observer whose influence was withdrawn from the course of action, despite numerous attempts to seize the reins’. Besides, we have Moltke’s criticism of himself, with reference to the employment of the Pomeranian Corps on the front of the First Army in the evening:

It would have been better if the Chief of Staff of the Army, who was present, had not approved of this advance to be made at such a late hour of the evening.And what about Sedan? The General Staff, in its study, states that

the execution of this battle so completely resulted from the preceding operations that not a single order from the Army Commander was necessary during the Battle to assure the uniformity of the action. I shall leave it to the reader to decide whether my sketch of the conduct of war by Moltke is closer to actual facts than the interpretation given by Wetzell.

Moltke, himself, derived an important lesson from his experiences of two wars; this lesson he laid down in the 1885 revision of the Instruction for Commanders of Large Formations, as follows:

In large-scale operations it is, as a rule, of little advantage to the commander to be able to supervise a part of the battle front. He still must rely upon messages and will often possess a clearer picture of the situation if he receives his information equally from all parts. Moreover, being removed from the confusing impression of the fight- ing, he may make his decisions more calmly. All commanders need their full mental ease and physical strength even after the final decision has been reached and, consequently, have every reason to be economical in this respect.I called these sentences a mental forerunner of the well-known allusion of Schlieffen to the ‘modern Alexander in the easy chair’.

To be continued …

For links other parts of this series, please see:

We shall win or lose the first campaign on adapting now and empowering decision down to battalion, squad, platoon and section. Have a plan but little groups of troublemakers* as plan B or plan Contingency is essential. Simply put if we engaged the Russian army today we’d have a systemic shock that can only be overcome by actions on the spot in the absence of orders or overall control.

We have neither fought nor maneuvered as Army, Corps or Divisions in 22 years (2003).

Instead we learned to among other fatal vices check with the lawyers first. Paralysis in the middle is certain.

We cannot have leaders or subordinate units waiting on orders that may well be *static hissing* they must have a clear and aggressive general direction and intent and the ability to take the battle and support in that direction and with that overall intent.

*Little groups troublemakers; I mean really they’re born for it, we do live training on this in the barracks every weekend.