Basic Training

Diary of a Stosstrupp Leader (Part 1)

17 December 1915

I obtained my Abitur.1 I was eighteen years old.

I spent Christmas at home. I would spend the next few Christmases in Russia and France.

27 December 1915

I traveled to reported to Morhange (Mörchingen) near Saarbrücken, where I reported for duty with the 97th Infantry Regiment (1st Upper Rhine), which had accepted me as an officier candidate (Fahnenjünker). During my journey, from Osterode in the Harz Mountains to Lorraine, I traveled through the valley of the Rhine and saw, for the first time in my life, that lovely river. It made quite an impression on me, reminding me of the many times I sang ‘The Watch on the Rhine’.2 Soon I would be among the watchers!

In the train station in Morhange I encountered two guards, who asked for my identification in a harsh, warlike tone. After that, I took the long road that led to the town, which was already completely dark. I wanted to enjoy a wash and put myself in order. However, that was not to be. The few inns and hotels in my garrison town were closed, so I laid down on a bench.

Shortly after sunrise, I heard a company on the march, singing ‘Germany, High in Honor’.3 It seemed as if they had just finished a field exercise.

I reported to the duty hut of my battalion, where I found three other candidates. We were dressed, like all other soldiers, in blue uniforms with gold buttons.

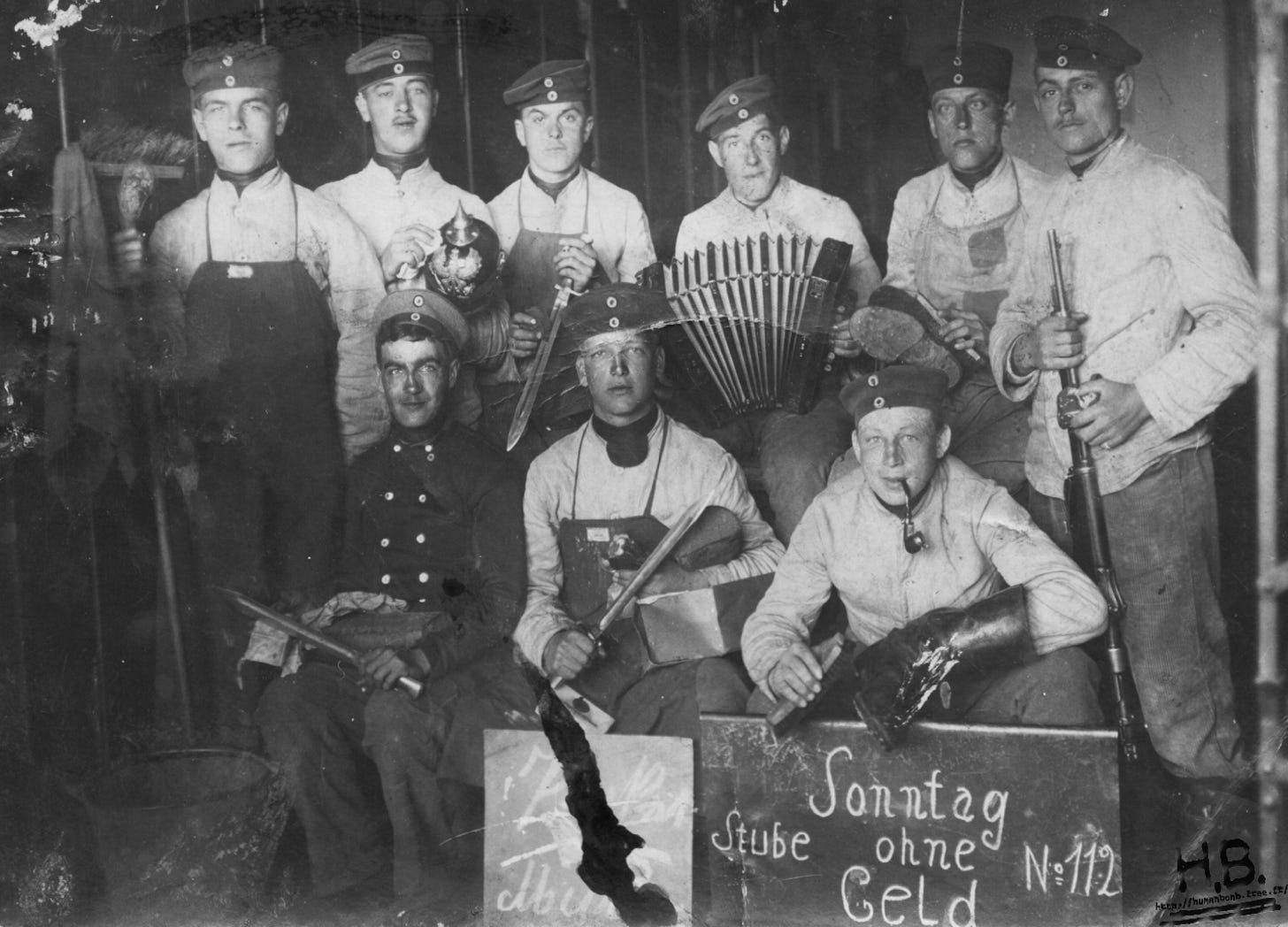

I was assigned to the 3rd Company, which put me in Squad Bay 11, where I lodged with fifteen men, mostly from the Rhineland or the Saarland. I received a bunk in a three-tiered bunk bed, a straw mattress, two blankets, a pillow, a locker, and a stool. In addition to beds, lockers, and stools, the room featured a great, crudely made table, a coal stove, coal scuttles, and a big tin urn for coffee.

28 December 1915 through 25 January 1916

I had no time to settle in. Drill in the barracks square asked much of us. The training officers paid special attention to the candidates among the rank-and-file. However, I did not suffer so badly, because, in the autumn of 1914, a reserve captain and four retired first sergeants (Feldwebel) who led a company of the Jugendwehr had prepared me well this work.

Nonetheless, like most former civilians, I did not enjoy the first four weeks of my military service. The quarters proved less than comfortable and the fare less than gourmet. Moreover, the candidates had to do everything that the other recruits did, whether close-order drill, bayonet exercises, carrying coffee urns, or toting coal.

28 January 1916

Yesterday was the birthday of the Kaiser. The goose-step (Parademarsch) that we had practiced for weeks pleased the commander of the Ersatz Battalion, Major von Zylander. We had cleaned and polished our leather gear, cartridge pouches, helmets, and boots to a high sheen.

I experienced an uncomfortable surprise. My squad-bay mates (Stubenkameraden) stole the last fifty marks out of my wallet.

It was a good thing I had bought myself a spare field-grey uniform on a recent weekend visit to Saarbrücken (tunic for eighty marks, boot trousers and long trousers for forty marks apiece, and boots for thirty-five marks). Otherwise they would have taken that money from me as well.

I had expected better of my fellow soldiers. Happily, I would experience a better sort of fellowship in the field, where soldiers sacrificed themselves to protect their comrades.

At first, I wanted to report the theft of my money. What good, however, would that have done for me? No one would confess to having taken the money. All of the men in the room, moreover, would probably have been subjected to punishment drills, which would have caused them to take out their frustrations on me at night. I wanted to save myself that trouble. So, I said nothing.

On the Kaiser’s birthday (27 January), each soldier did little in the way of duty, and was allowed to get drunk without being punished. My squad-bay mates did a proper job of this. After all, they were well supplied with money.

After 29 January 1916

After two more months, basic training came to an end. Duty became more interesting. There was thorough training in rifle marksmanship. Drill by complete platoons and companies, road marches (both short and long). These, made with full pack, proved especially difficult for the other officer candidates. Long walks in the countryside with my old teacher Herr Schirmer had, however, accustomed me to such exertions.

For the improvement of our practical training, we four candidates of the Ersatz Battalion, who had just been promoted to the proud rank of lance-corporal (Gefreiter), were placed in the care of an efficient and able first sergeant. We also received instruction in horseback riding and the use of the bayonet. Thus, we filled our days. In the evening, and on Sundays, we were also obliged to put on our spare uniforms and report to the officer’s club, so that we might be evaluated for our behavior off duty.

In the summer of 1916, we four candidate lance-corporals (Fahnenjunker-Gefreite) were provided with field equipment and sent to the maneuver grounds at Döberitz. There, a large number of officer candidates attended a course, conducted by able officers and efficient first sergeants, that last for several weeks.

We were quartered in large wooden barracks, which held lots of triple bunk beds. It was not without justice that the maneuver grounds were known as ‘a big can of sand’. Our duties demanded much of us, and the summer heat produced many drops of sweat. At the same time, we enjoyed Sunday visits to Berlin, where my grandparents lived.

After the hard but beautiful excursion, we four candidates, who had been promoted to the rank of ‘officer candidate sergeant’ (Fahnenjunker-Unteroffiziere) returned to the Ersatz Battalion in Morhange. There we performed a variety of duties, especially field exercises with live ammunition. We also took part in the exercises for candidates for reserve commissions, which were conducted by an especially able, but rather old, senior officer.

Once, when one of the candidates overslept, and, as a result, failed to complete the sketches that illustrated his solution to a tactical decision game, the instructor said ‘If you want to become an officer, then you must learn that each day holds twenty-four hours, and not just twelve. Take note. Come autumn, our regiment will need replacements. And autumn will come sooner than you think.

To be continued …

Source

Alwin Lydding Meine Kriegstagbuch (My War Diary), unpublished manuscript, Bundesarchiv (German Federal Archive) N 382/1

For Further Reading

Earned by passing a rigorous examination, an Abitur entitled the holder to study at a university.

Die Wacht am Rhein (YouTube)

O Deutschland hoch in Ehren (YouTube)

Superb; excited for the subsequent installments.