We have only found that men enlist, become discontented, and leave usually in the first and second years of their enlistment. — Report of Brig.- Gen. Stanley, 1884

“What causes desertion in our army?” This question has been asked for many years, and there has been no lack of answers. They have come from every source. General officers, in their annual reports, each year offer solutions of the question. Department Judge-Advocates have compiled long tables of statistics in their endeavors to throw new light upon the subject. Field and line officers have contributed to the list; and non-commissioned officers and privates have given their views and opinions in the columns of our various Service journals.

The list of causes assigned, and of remedies suggested would alone exceed the limits of this paper. The principal causes assigned by various writers are, poor food, too much manual labor, tyranny of officers, ill-treatment by non-commissioned officers, lack of education in the rank and file, insufficient pay, and excessive length of the term of service.

In adding my answer to the list, I wish it understood: 1st. That I deal only with desertion in the near past and in the present. 2d. That my ideas on this subject are the offspring, and not the fathers, of the facts which I have collected. 3d. That my opinions are not alone derived from my own experience and observation, but from consultation with others, both officers and enlisted men, whose length of service far exceeds mine.

The calculations in official reports showing percentage of desertions are almost invariably based upon the allowed strength of the Army; but as a large portion of our troops are re-enlisted men, who rarely desert, such calculations evidently do not show the extent of the evil. Let us instead compare the number of desertions in a given year with the number of recruits enlisted in that year. By this method we find that in 1884 the number of desertions was 42 percent of the number of recruits enlisted; in 1885 it was 43 percent; in 1886 42 percent; and in both 1887 and 1888 38 percent. In other words, there have been more than four desertions for every ten recruits enlisted during the past five years.

The financial importance of these losses has been so repeatedly set forth that it need not again be shown. But there is one element of danger to the Army that seems not to be generally considered. In the past five years we have had more than 30,000 deserters; a small percentage of these have, in various ways, been returned to the Army, but the larger portion are now in civil life. They are scattered through the various States; nearly all of them have votes, and every man has some influence. Those votes and that influence may some day help to decide important questions for the Army, and perhaps have an injurious effect on the military policy of the Nation.

There can be no doubt that each of the various causes assigned as “the one fruitful cause of desertion” has contributed to the general result. But investigation shows that no one of these causes is co-extensive with desertion. The Army is generally well-fed. It is true, however, that some companies fare far worse than others, but desertions occur in both. The quantity of food is always sufficient, and the quality good, what- ever may be lacking in variety; and I do not believe that any man now deserts on account of poor food.

Excessive fatigue is often urged as the prime cause, and yet in the post of Fort Leavenworth 6 4/10 per cent. of the enlisted strength deserted during the last fiscal year, and during that year there may be said to have been no fatigue in this post.1

Tyranny of officers and ill-treatment by non-commissioned officers is a cause often assigned. Yet Captain J. G. Bourke, Third Cavalry, special inspector upon the subject of desertions, says: “I have not found any instances of ill treatment, although great pains were taken upon this point.” Speaking from my own observation in ten years’ service, more than half of which was as an enlisted man, I agree with Captain Bourke.

It has been suggested (not as a special remedy, but as a sort of tonic) that by educating the rank and file of the army we would cure desertion. When we reflect that at the outbreak of the late War defections from the Army were confined to the commissioned, and presumably, better educated portion, while the enlisted portion, to a man, remained loyal, it is hard to see the force of this suggestion. The experience of the world proves that education rarely brings content, but rather the reserve, and records of boards of survey show that the deserter is generally a well educated man.

Increase of pay has been also prescribed as a remedy for desertion. Increase of pay would probably bring more men to the recruiting office, but would hardly prevent desertion. The man who intends deserting to-morrow might be kept in the Service by raising his pay from thirteen to seventeen dollars per month, but it must be his pay alone that shall be increased; if all his comrades receive the same increase he no longer feels rich by comparison, and “to desert or not to desert” again becomes a question entirely independent of pay.

It must be considered that the pay of the private is already liberal, not only by comparison with other armies (he is the best paid private in the world), but liberal as compared with the pay of unskilled labor in civil life. “Thirteen dollars per month” seems small pay, until we reflect that in addition the soldier receives board, lodging, clothing and medical attendance; and that his pay is constant, whether on duty or off, in sickness or in health.

Then he has other advantages which must be considered. The commissary cheapens to him the price of many luxuries; in the reading-room he has access to newspapers from all parts of the United States, and he may choose from the hundreds of volumes to be found in every post library. These privileges the civilian either enjoys not at all, or only by payment of small fee which, large or small, must be considered in comparing their respective wages.

But it is argued that an increase of pay would secure a better class of recruits, and that it would cause men to look upon the service as a life calling. When all other explanations fail, “carelessness in recruiting” is made to account for the prevalence of desertion; and nine of every ten writers on the subject advocate securing “a better class of recruits” as the final remedy. I cannot coincide with this statement.

Before entering the Service I lived for some time in the East, West and South; since then I have been stationed in Texas, the Indian Territory, Kansas and Nebraska. Having always tried to observe my fellow men, I think that a better class of recruits can be secured, no matter what the pay, because, in my opinion, no better class exists. Bear in mind that it is not alone mental, moral or physical qualifications that we require in the recruit, but a combination of all three. And, all three to have due weight, the enlisted men of the United States Army will bear comparison with any class of men in the world.

As for men enlisting with the intention of remaining in the Service for life, a slight knowledge of human nature teaches that few men, possessing the qualifications we demand, will ever adopt, as a life calling, one which requires perpetual celibacy.

Reduction of the term of enlistment has been strongly urged as the great remedy for desertion. This must be regarded as a concession, not as a cure, and, for military reasons, only to be adopted as a last resort.

A systematic attempt to investigate the subject of desertion was first made in 1882, when orders from the Adjutant-General’s Office directed that a Board of Survey be called in the case of each deserter, to ascertain, if possible, the cause of his desertion. It was expected that by this means the question “Why do men desert?” would be satisfactorily answered: and the annual reports for the following year were eagerly awaited. It is needless to say that these expectations were not fulfilled.

The annual reports of Department Commanders for 1883 and 1884 show that in only about 33 per cent. of the cases was any probable cause assigned; while among the causes given “dissatisfaction” appears more frequently than any other. It is evident that assigning dissatisfaction as a cause for desertion is equivalent to saying that a man is blind because he cannot see. Therefore, eliminating “dissatisfaction” from the list of causes, we find that Boards are unable to assign any probable cause for about 80 percent of the cases investigated.

If we consider the situation we shall not wonder at this lack of success. The man has gone. Why he went no one knows, except, possibly, some intimate friend in whom he confided, and that friend will not care to violate his confidence. The Board cannot examine men under oath; but, even if it could, the result would, doubtless, be the same. The whole thing becomes a matter of opinion, and the finding of the Board is of about the same value as that of a coroner’s jury in a case where the remains are missing.

Another source of information is found in the statements before courts martial, of deserters who have been apprehended. If we believe their stories, we must conclude that each earned a martyr’s crown before deserting. But investigation rarely confirms their statements.

I do not believe that one out of four deserters can tell exactly why de deserted. If asked, however, they always state some cause: for only poets and fools are willing to acknowledge that they do not know the reasons for their own acts.

The quotation with which this article opens tells the result of investigation made by one who had exhausted official inquiry.

But where inquiry fails analysis may succeed. Let us, therefore, attempt to analyze this problem:

The object which all men seek to pursue in life is their own happiness. All actions are directed to this end. Therefore, when a man abandons one occupation for another it proves that his action is the result of a mental comparison, and that the advantages offered by the new employment appear to him greater than those he enjoyed in the old, or, as commonly stated, he is trying to “better his condition.”

But when a man abandons one employment with no certainty of finding another, and, as a consequence of his act, incurs the risk of severe punishment, when he flies from the “ills he has, to those he knows not of,” it shows that there has been no mental comparison, but that he has simply found the life he flees from intolerable.

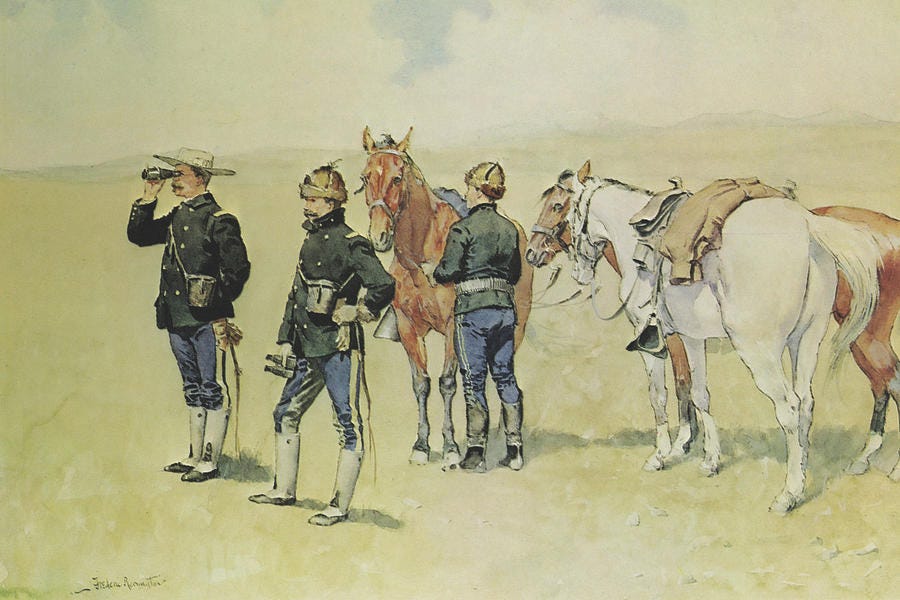

This post is a verbatim copy of an article by Lieutenant William D. McAnaney, of the 9th Cavalry, that was originally published in Volume X (1889) of the Journal of the Military Service Institution of the United States.

As used here, the term “fatigue” refers to manual labor (such as digging ditches or cutting wood) rather than tiredness caused by performance of purely military duties.

It is notable that the author was serving in the 9th Cavalry at the time yet he makes no mention of race as an issue. During the previous decade, the 9th lost about 44 troopers during action principally against the Apaches and they received 11 Medals of Honor.