This post continues a series begun with

While slogans resemble historical legends, the latter dwells in the neighborhood of the awesome and the sublime. Thus, we should believe in gods and heroes, refrain from debunking legends, and avoid the replacement of the courageous ‘I’ with the milquetoast ‘one’. Thus, I prefer to imagine Nero as an imperial monster who went to bed by the light of burning Christians than as a clever, if somewhat odd, dictator of the modern type. I am thankful to have grown up in a time and place which celebrated the dazzling mind and skillful hand of the Iron Chancellor, who, rather than clobbering mindlessly with a sledgehammer, dodged, forbore, and waited before striking home with his rapier.

In my own field, the profession of arms, I condemn clichés for a very specific reason. Because, in that realm, they can work, and, indeed, have worked, deadly effects. Because thousands of human lives have been sacrificed on the altar of military catchphrases, never out of malice, to be sure, but rather as a result of an absence of independent thought. Out of a sense of responsibility for the future, which is far more important than the past, I want to examine the meaning of some military clichés. Perhaps then someone else will reflect upon their meaning before basing his actions upon them.

Pacifism

Anyone who understands the essence of war, its needs, demands, and consequences - that is to say, a soldier - will think far more seriously about the possibility of war than the politician or businessman, who cooly compares gains against losses. After all, while giving up one's own life may not be difficult, a profession that requires a man to risk the lives of others places a particular burden on his mind.

The figure of the saber rattling, war mongering general is an invention of poisonous, unscrupulous political struggles, a stock character from the funny pages, a caricature.

He who has seen war through bloodshot eyes, who, from a well-sited observation post has looked over the battlefields of a world war, who has seen the sufferings of inhabitants, whose hair has been turned gray by the ashes of many burned villages, who must answer for the lives and deaths of many, the experienced and knowledgeable soldier fears war much more than the man of imagination who, having had no experience of war, can only speak of peace.

If you wish to call this attitude to war ‘pacifism’, a pacifism built on knowledge and born of a sense of responsibility, be my guest, but please do not confuse it with the sort of pacifism based on the debasement of the nation and blurry-eyed notions of international cooperation.

In particular, while the soldier welcomes all efforts aimed at reducing the likelihood of war, but he will never march under the banner of a slogan like ‘no more wars’ because he believes that higher powers decide on war and peace than princes, statesmen, parliaments, treaties and alliances, namely the eternal laws of the rise and fall of nations. If, in the face of this fateful struggle, he wants to disarm his own people, prefers to see it weaken in the shackles of a hostile neighbor than support his countrymen preparing for legitimate defense, the pacifist ought to be hanged on a streetlight, even if the streetlight is one of a purely moral kind.

The concept of pacifism thus covers both the understandable love of peace of the experienced, responsible man and the knavish submissiveness of those who call for ‘peace at any price’. It is thus, in the clearest sense of that word, a cliché that we can do without.

To be continued …

Source

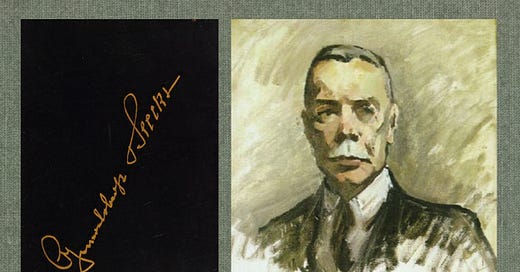

Hans von Seeckt Gedanken eines Soldaten (Berlin: Verlag für Kulturpolitik, 1929)