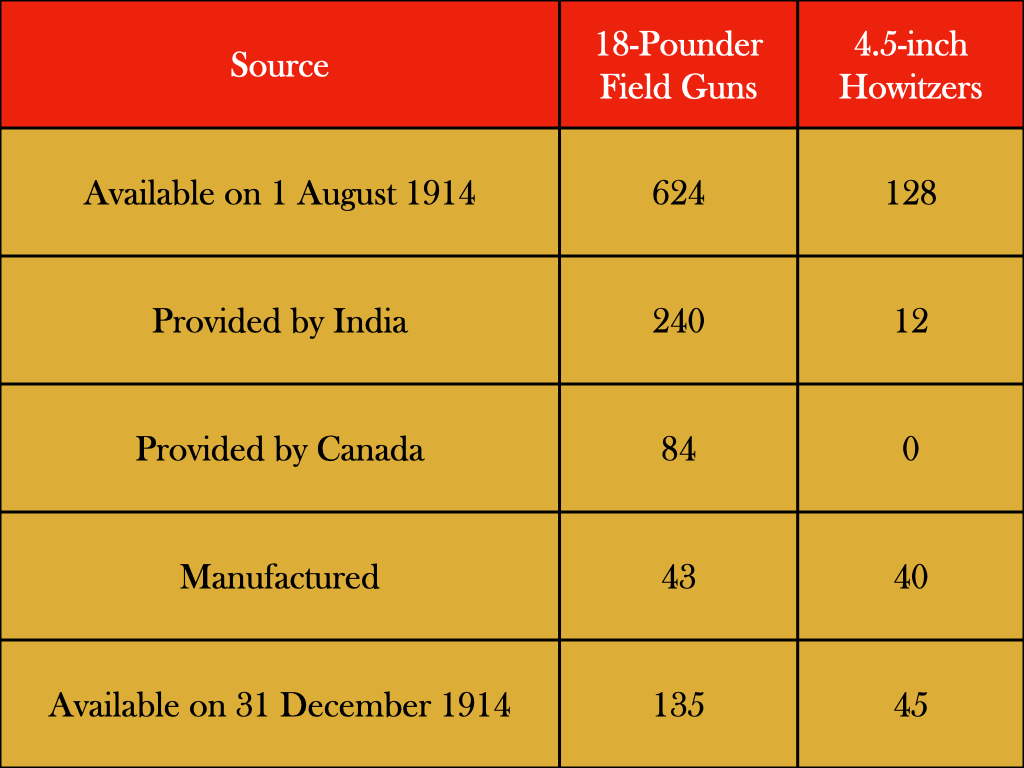

On 12 October 1914, the master general of the Ordnance, Major-General Sir Stanley B. Von Donop, made a formal argument for limiting the initial provision of field guns to New Army divisions to four pieces per battery.1 In doing this, he explained that the orders he had placed with various factories for the manufacture of 18-pounder field guns called for 892 such weapons to be delivered by 15 June 1915. (This was a considerable increase over the 626 field guns of that type ordered during the first month of the war.)

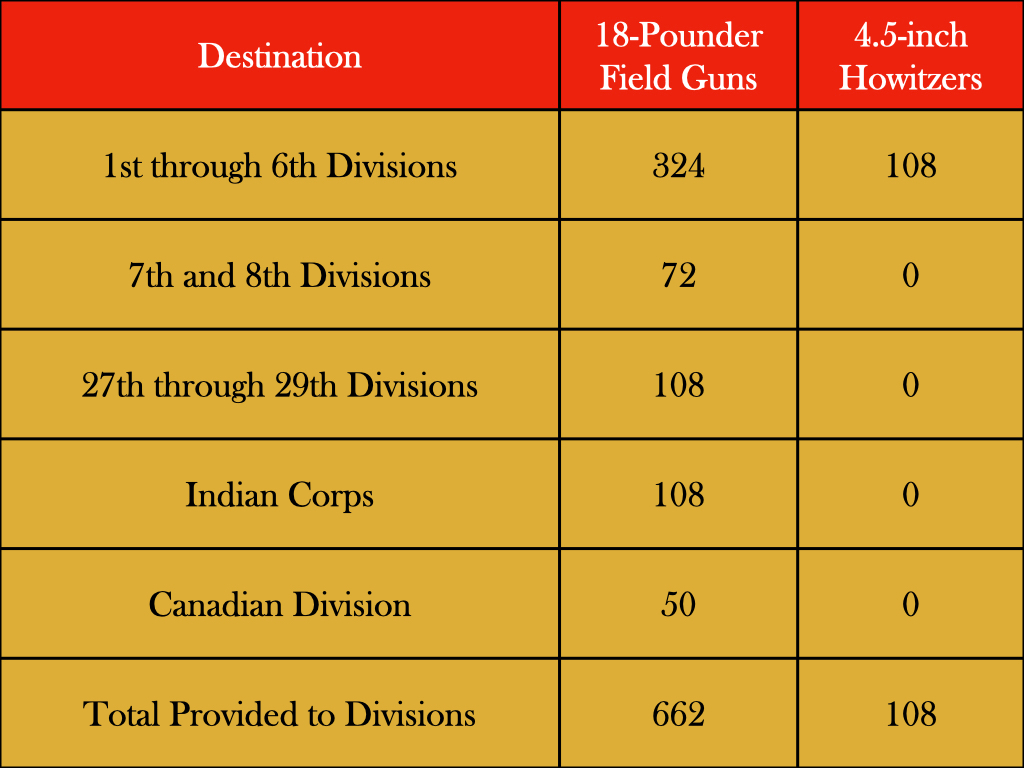

When a small allowance was made for error and delay, Von Donop argued, this volume of orders provided a reasonable expectation that 864 field guns would be delivered before the middle of 1915. (All of the orders, after all, had been placed with established manufacturers that had been working with the British Army for decades.) These 864 field guns were sufficient to arm nine four-gun field batteries in each of the twenty-four New Army divisions then being formed.

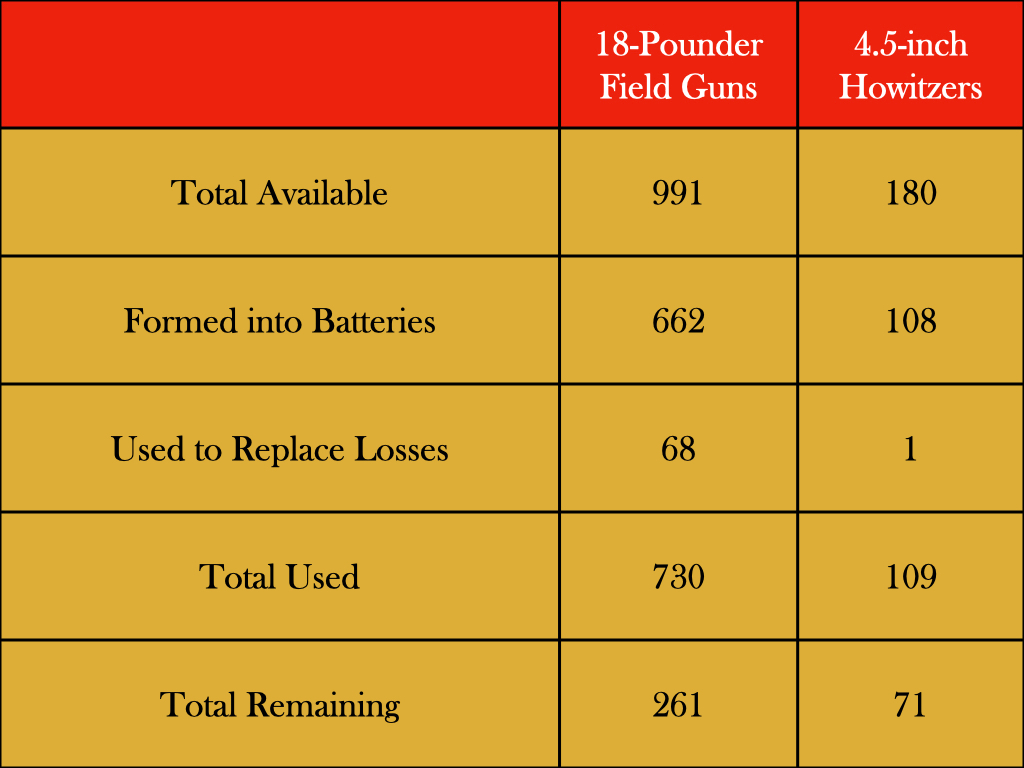

However, the provision of the 1,296 field guns needed to give nine six-gun batteries to each of these divisions, struck Von Donop as well beyond the capabilities of these manufacturers.2 (Von Donop’s predictions proved accurate. Between the beginning of the war and 1 July 1915, the British Army took delivery of 803 new 18-pounder field guns.)3

Von Donop’s proposal seems to have been well received, not so much for the figures that provided its foundation, but for the way that it satisfied both sides of a debate that had been simmering within the British Army for a period of years. For several years, advocates of old-fashioned six-piece field batteries had waged a polite but heated war of words against those who championed four-gun field batteries à la française.

This debate came to a boil in 1911, when enthusiasm for French methods within the Royal Field Artillery was at its height. To help settle this matter, a full- scale experiment was conducted to see if a four-piece battery was indeed easier to move, hide, register, and control than a six-piece unit.4 Though this experiment failed to demonstrate the superiority of the four-piece organization and thus resulted in an official decision to retain the traditional six-piece structure, a number of senior soldiers remained convinced of the inherent virtues of the four-gun battery.

The most prominent of the enthusiasts for four-gun field batteries was Sir John French, the ‘field-marshal commanding-in-chief’ all British Empire forces on the Western Front for the first sixteen months of the war. In a letter to Lord Kitchener dated 28 November 1914, French wrote, “I am personally in favour, and I always have been, of the four-gun battery. I have tried hard to get this change brought in at the same time as I effected the double-company organization for the infantry.”5

In the two weeks that followed his report to the Cabinet Committee, Von Donop placed a large number of additional orders for artillery pieces of the three types then used by infantry divisions. As these orders were not accompanied by any significant expansion of capacity, sober observers (including Von Donop himself) were less than optimistic about the ability of manufacturers to fulfill their ambitious promises. This multiplication of orders might nonetheless have had the effect of vindicating the advocates of the six-piece battery.

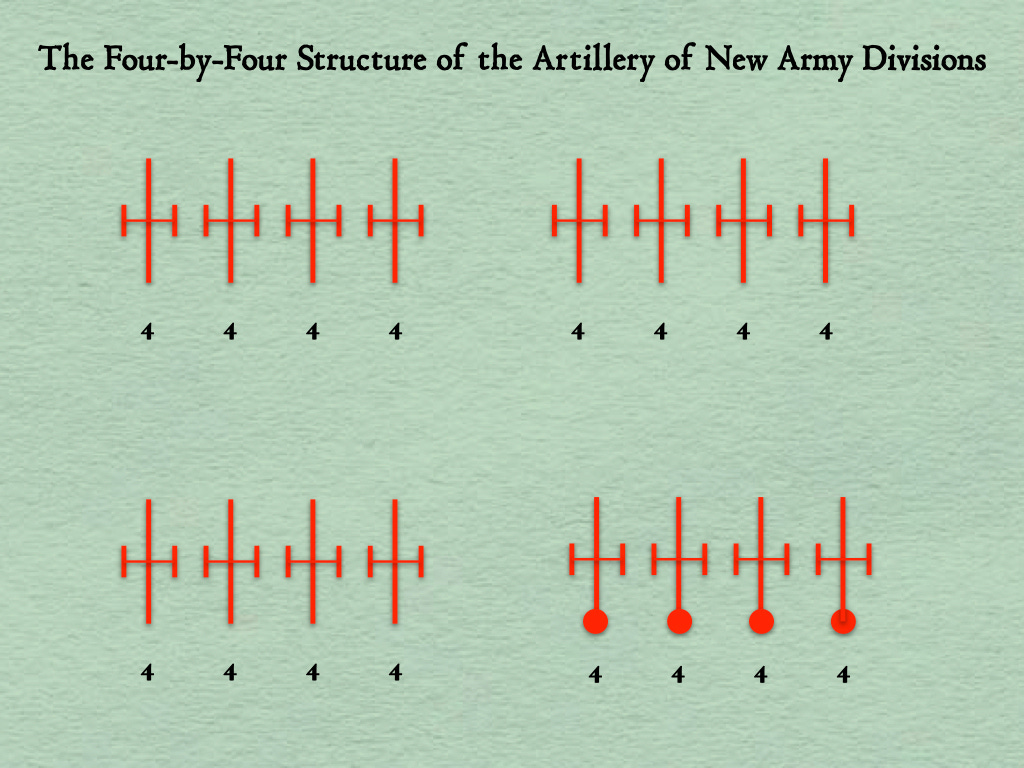

The great increase in orders for new field pieces coincided with the adoption of a very different solution to the problem of providing field artillery to New Army divisions. This new approach, which first came to light in the late autumn of 1914, called for the radical restructuring of the field artillery brigades of New Army divisions. Instead of three six-piece batteries (for a total of eighteen pieces), each New Army field artillery brigade was to consist of four four-piece batteries (for a total of sixteen pieces.)6

At first glance, the adoption of the ‘four-by-four’ structure for field artillery brigades made very little sense. The new structure was a complete novelty to the British Army of the time – something that officers had never encountered in practice and rarely engaged in the realm of theory.7 It was, furthermore, something that cannot be adequately explained by a shortage of the right sort of weapons. The reform reduced the total number of field pieces needed by each New Army division by eight, and thus the total number of field pieces required to arm the twenty-four or so New Army divisions then being contemplated by about two hundred. This number, however, is too large to have served as a reasonable margin for error for the orders that had recently been placed with the ordnance factories. It is therefore likely that the chief motivation for the adoption of the “four-by-four” structure was something other than a desire to economize on field guns and howitzers.8

This article belongs to a series, the other installments of which can be found by means of the following links.

British Infantry Divisions (1914-1918) (I)

British Infantry Divisions (1914-1918) (II)

British Infantry Divisions (1914-1918) (III)

British Infantry Divisions (1914-1918) (IV)

British Infantry Divisions (1914-1918) (V)

British Infantry Divisions (1914-1918) (VI)

British Infantry Divisions (1914-1918) (VII)

Sir Stanley Brenton Von Donop (1860-1941) was descended from a family of Hessian origin that had been closely associated with the British Army since the late eighteenth century. Born and raised in Great Britain, he was a career artillery officer with a strong interest in the technical side of his profession. Prior to becoming the Master General of the Ordnance (7 February 1913 to 3 December 1916), he served as commandant of the Siege Artillery School at Lydd (Kent). While a number of official documents, including some related to Von Donop’s knighthood, spell the name in the German style (with a lower case ‘v’), the catalogues of the British Library, the National Archives and the National Portrait Gallery treat the ‘Von’ as an integral part of the name rather than as a separable preposition.

Untitled notes dealing with the meeting of the Cabinet Committee on 12 and 13 October 1914, Papers of Sir Stanley Von Donop, TNA, WO 79/79.

Untitled notes dealing with the delivery of 18-pounder field guns, 4.5-inch howitzers, and 60-pounder heavy guns between the start of the war and 1 July 1915, Papers of Sir Stanley Von Donop, TNA, WO 79/79.

Report of the Committee Appointed to Carry Out Certain Field Artillery Trials on Salisbury Plain, October 1911, TNA, WO 33/3024

Kitchener Papers, TNA, PRO 30/57/49

The first mention of the ‘four-by-four’ scheme in the records of the Army Council appears in the minutes for a meeting of the military members held on 12 November 1914. On that day, the military members decided that the 27th Division should have eight four-piece field gun batteries. Minutes for the Meeting of the Military Members of the Army Council, 12 November 1914, TNA, WO 163/45.

Among the many organizational schemes discussed in the Journal of the Royal Artillery of the years prior to World War I, only one came close to the ‘four-by-four’ structure adopted in 1914. This scheme called for a field artillery brigade that was divided into two eight-piece batteries, each of which consisted of two four-piece troops. C. B. Thackeray, “Eight Gun Batteries” Journal of the Royal Artillery, March 1914.

The figures used in the three charts at the end of this article come from: Number of Guns Possession at Outbreak of War, Von Donop Papers, TNA, WO 79/84; Minutes for the Meeting of the Military Members of the Army Council for 5 October, 1914, TNA, WO 163/45; A. Fortescue Duguid, Official History of the Canadian Forces in the Great War, 1914-1918, (Ottowa: J.O. Patenaude, 1938), Appendix 127a, page 104; and War Office, Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire During the Great War, 1914-1920, (London: HMSO, 1922), page 491.