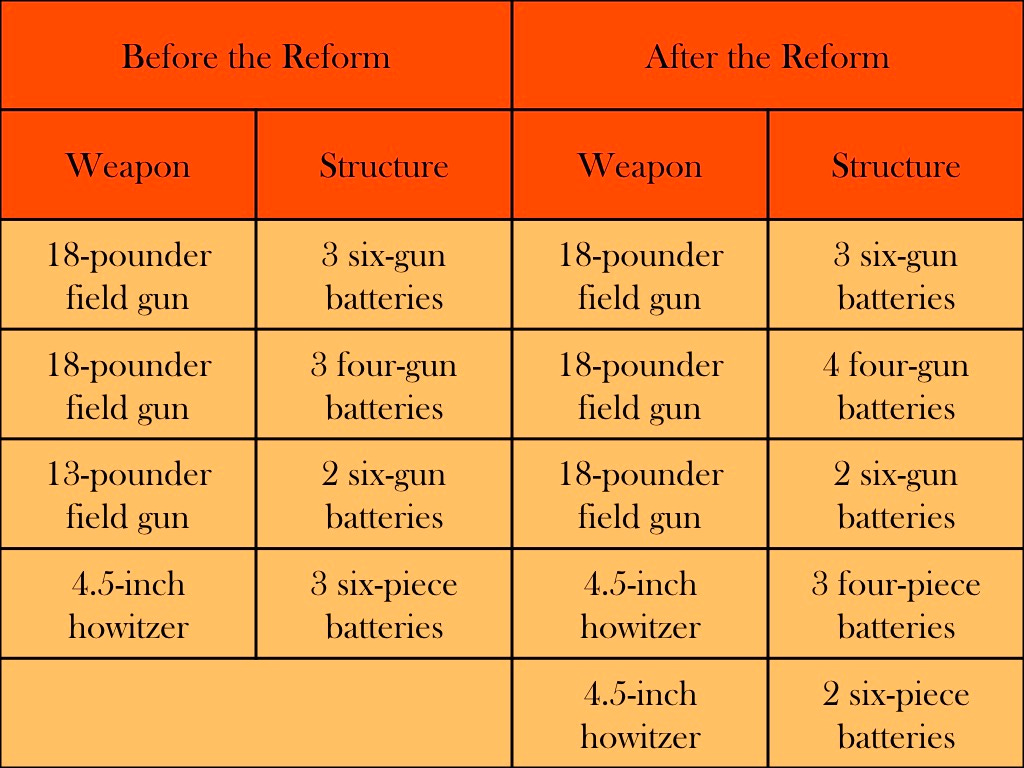

In February of 1915, the War Office began a three-stage program to balance the field artillery establishments of the divisions then serving on the Western Front. The first step in this reform transferred six-piece field batteries from four of the divisions of the original Expeditionary Force to the two improvised Regular Army divisions (the 27th and the 28th) that had been making do with substandard field gun establishments. As a result of this reform, all six of the divisions involved ended up with forty-eight 18-pounder field guns.)

The second step in the scheme redistributed the 4.5-inch howitzers serving on the Western Front in a way that ensured that each of the divisions that took part ended up with a brigade armed with twelve weapons of that type. (Each division of the original Expeditionary Force lost a single six-piece battery and, as a result, ended up with two six-piece batteries. Each New Army division retained three of its four four-piece howitzer batteries.)1

In the last step in the reform, which began in June of 1915, transformed the horse artillery batteries of the 7th and 8th Divisions into the functional equivalent of field gun batteries. To this end, those batteries replaced, on a one-for-one basis, the 13-pounder guns they had been using with 18-pounder field guns.2

Thanks to this effort, the middle of August of 1915 found most British divisions on the Western Front in possession of forty-eight 18-pounder field guns and twelve 4.5-inch field howitzers. In other words, each of these formations possessed the same number of artillery pieces of each standard type as one of the New Army divisions that had recently arrived on the Western Front.

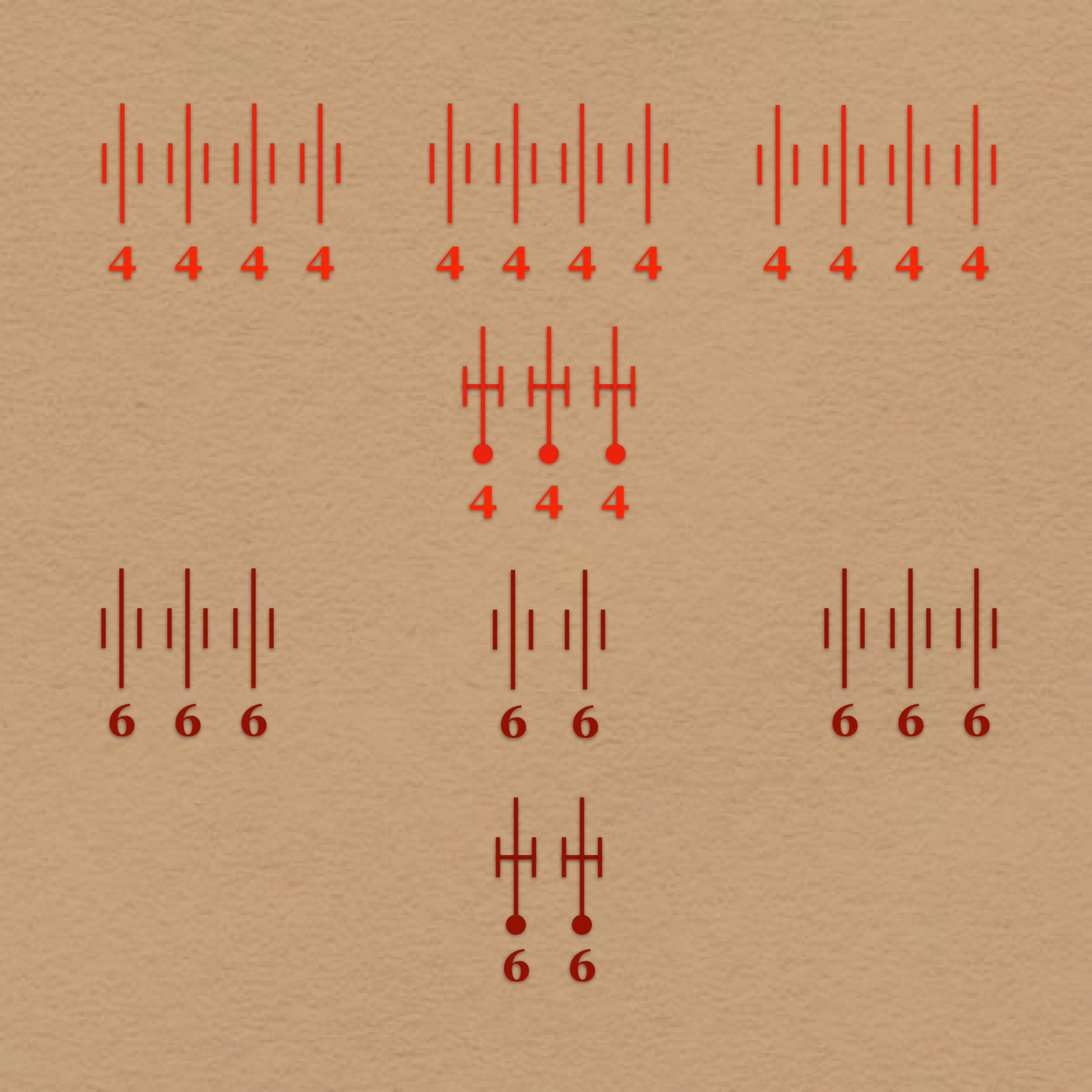

The assignment of these weapons to batteries and brigades, however, varied considerably. Indeed, while this reform decreased diversity of armament, the number of different types of field artillery brigade serving in France and Flanders actually increased.3 (This increase in patterns resulted from a policy of allowing the first eight divisions to arrive on the Western Front to retain their six-piece batteries, even if it did disrupt the organizational symmetry of field gun brigades.)

The Guards Division, which was formed on the Western Front in August of 1915, enjoyed an exception to the general rule that an infantry division of the Regular Army (whether New Army or made up of pre-war elements) be limited to twelve 4.5-inch howitzers. Rather, the new formation received a complete divisional field artillery establishment of the New Army type. Thus, when it took its place in the trenches, the Guards Division possessed four four-piece howitzer batteries.4

In February 1916, Territorial Force brigades in France started to receive the additional batteries that they would need in order to reach the New Army standard of twelve field gun batteries and three howitzer batteries. Most of these batteries were formed “from scratch” in the United Kingdom.5 Three, however, were provided by divisions of the original Expeditionary Force that had managed to retain more than their fair share of field batteries.6

The reform of the artillery of Territorial Force divisions, which was complete by the middle of May 1916, thus had the effect of reducing the number of distinct field artillery establishments on the Western Front from four to two. This arrangement, however, would only remain in place for a few weeks. Beginning in May 1916, the British Army launched the second major reform of the field artillery establishments serving on the Western Front.

The first step in this second reform was the abolition of the distinction between howitzer brigades and field gun brigades. This measure, which anticipated the provision of six additional howitzers to each division, resulted in the conversion of all field artillery brigades into “mixed brigades.” (Each of these consisted of three field gun batteries and a single howitzer battery.)7 The second step recast the sixteen existing four-piece batteries into twelve six-piece units.

Marvelous to say, the second reform owed much to the same desire to economize on experienced field artillery officers that had motivated the earlier shift to the four-piece battery. However, rather than husbanding the old captains and majors who had learned their trade in the long years of peace, the new reform economized on the young battery commanders who had proved their abilities in the course of the previous year.8

Becke, Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 1, pp. 37, 45, 53, 61, 69, and 77 and Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 3A, pp. 7, 31, 49, 57, 75, 91 and 99 and Archives Canada, War Diary, 118th Howitzer Brigade, Royal Field Artillery and War Diaries, Second Army, Administrative Branches of Staff, AC, RG9 Militia and Defence (III-D-3), Volume 5068, Reels T-11131 and T-11132

Becke, Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 1, pages 101 and 109

The field artillery brigades of the Indian Corps, which had already been earmarked for transfer to Mesopotamia, did not participate in the second phase of the field artillery reform of 1915. Perry, Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 5B, pp. 53 and 89

Becke, Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 1, pages 28-29

Becke, Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 2A, pages 64-65, 72-73, 80-81, 88-89, 96-98, 104-105, and 136-137

Becke, Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 1, pp. 52-3 and 76-77.

The idea of forming mixed brigades was far from novel. A discussion of the composition and employment of various types of mixed field artillery brigades, for example, took place at the General Staff Conference of 1913. Conference of General Staff Officers at the Royal Military College, TNA, WO 279/48 and Headlam, The History of the Royal Artillery, Volume II (1899-1914), pages 229-30.

Alan F. Brooke, “The Evolution of Artillery in the Great War,” Journal of the Royal Artillery, 1925, page 371.