Bracketing

Tactics Made Simple

In the middle years of the nineteenth century, gunners in the service of the king of Prussia developed a technique for placing projectiles onto a target. On 9 November 1870, at the battle of Coulmiers, Lieutenant Alexandre Percin of the French field artillery found himself on the receiving end of artillery fire adjusted by means of this method, which he called “the fork” (la fourchette.) Lucky enough to escape the fate intended for him, Percin survived to provide an account of the use of what present-day artillerymen call “bracketing.”

“... of the six pieces of my battery, only the two that I commanded were visible to the enemy. The other four were masked by a fold in the ground. Thus, all the German guns which were firing on us were aimed at my section. I was very afraid; it would be stupid to try to deny it. Was its not Turenne who said ‘My carcass trembles?’ Was it not Ney, the ‘bravest of the brave,’ who wrote: ‘Who says he had never been afraid is three times a liar.’”

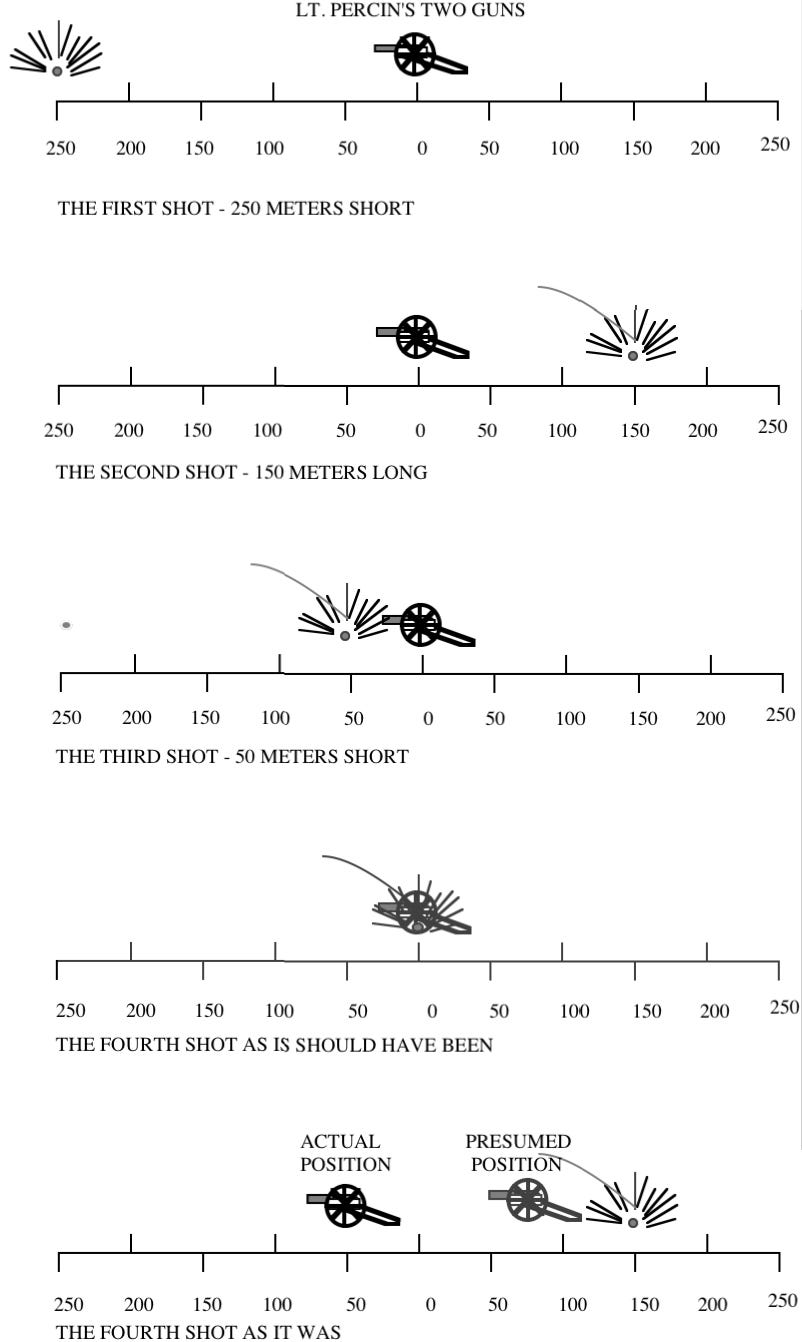

“The first German salvo fell 250 meters in front of me. The Germans lost no time in perceiving this. Their shells, in effect, equipped with percussion fuses, exploded when they hit the ground, and, from the fact that the smoke of the explosion was in front of the target or that the target was in front of the smoke of the explosion, they were able to determine whether the shot was short or long.”

“...Having observed that their first salvo was short, the Germans extended their fire by 400 meters. The second salvo should have been short as well, but it was long by 150 meters. The German shells passed over my head, producing a very disagreeable whistle. I became more and more afraid. Mechanically, I lowered my head. I felt very ashamed, because my gesture was immediately imitated.”

“The Germans now shortened their fire to 200 meters, thus taking the average of the two previous changes in range. Their shells fell fifty meters in front of me.”

If Percin and his guns had stayed in the same position, chances are that the next German shell would have landed on top of them. At that moment, however, the two French guns and their brave commander were saved by the orders of a nervous officer. In order to seem to be doing something, Percin’s battery commander ordered the lieutenant to move his section fifty meters towards the front.

Too scared to remind his superior of the idiocy of the command, Percin obeyed. He shouted long practiced words of command. His gunners hitched up the gun teams and moved them forward to the point where the German shell had just hit. Two minutes later, the fourth German salvo fell. Rather than landing on top of Percin and his men, however, the shells fell harmlessly a full 200 meters behind their intended target.

The only explanation that Percin could come up with was that the German battery commander had made a mistake. The German officer, Percin believed, had mistaken Percin’s forward movement for a retreat. (This, after all, would have been the sensible thing to do! Distinguishing forward movement from rearward movement a mile or two away is, moreover, far more difficult than one would imagine.) As a result, the Germans had extended their fire by two hundred meters in an attempt to catch the French before they reached cover.

For the moment, at least, Percin and his men were safe. Percin had enough subsequent contact with German batteries using bracket ing to allow him to recall, a full sixty years later, “the apprehension that the prospect of the third salvo inspired in us when the first [salvo] was long and the second was short.” Given that Percin’s experience was not unique, it is not surprising that, during the period of reform that followed the Franco-Prussian War, the French artillery made bracketing a key element of their approach to the art of gunnery.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, French artillery officers built devices designed to facilitate la fourchette. One of these was the déboucheur, an automatic fuze setter that allowed bracketing to be used with shells that burst in the air as well as shells that exploded when they struck the ground. Another was the calibration of elevation mechanisms in a way that allowed a gunner to set the range for his piece with a simple turn of a crank.

Source: Alexandre Percin Souvenirs Militaires, 1870-1914 (Paris: Edition de L’Armée Nouvelle, 1930) pages 81-87

For Further Reading:

To Share, Subscribe, or Support:

The German commander might also have been unmindfully sticking to the formula for a bracket, which would call for an add of 100 meters at this point, especially if one was unsure of the range, given that the target had moved.

I recall reading a discussion of engagement techniques by WW II German Sturmgeschutz units, which normally used the bracketing technique described here, although much abbreviated, and that it was often superior to fire from panzer units.

Super clear and interesting. Thanks!