The estate of the late John Sayen has graciously given the Tactical Notebook permission to serialize his study of the organizational evolution of American infantry battalions. The author’s preface and the previous section of this book may be found via the following links:

The Infantry Board’s recommendation to solve the problem posed by incompetent infantry battalion commanders was not so much to improve their training or selection but to increase their rank. Henceforth, they would be lieutenant colonel s rather than majors. The official rationale for this was that lieutenant colonels would bring more maturity, seniority, and experience to their jobs than majors would. The obvious difficulty, however, is that if all infantry battalion commanders were lieutenant colonel s, then the infantry would need many more lieutenant colonels and would have to promote junior officers much more rapidly in order to obtain them. Thus, an officer could reach the rank of lieutenant colonel well before gaining the additional maturity and experience that was the justification for making him a lieutenant colonel in the first place.

However, the Superior Board wanted each battalion to have a major as well. Noting that platoons, companies, and regiments already had officers (non-commissioned officers in the case of platoons) designated as seconds in command, or executive officers, each lieutenant colonel commanding an infantry battalion (majors would still command battalions of other than infantry) should have a major as his executive officer.

The Board justified its decision by pointing out that as the core of any combined arms force, an infantry battalion could expect to be supported or augmented by machineguns, field artillery, engineers, and even tanks. The battalion commander would have to be an able coordinator of all of these elements with that of his own unit and he needed more rank and experience to accomplish this. If he became a casualty, a mere company commander would not suffice to take his place; another field grade officer must perforce succeed him.

The remainder of the proposed battalion headquarters would include a captain who would constitute the third (Bn-3) staff section responsible for plans and training. In practice, however, the battalion executive officer functioned as the real S-3 and the S-3 officer merely assisted him. A first lieutenant served as Bn-1, or adjutant, and would also command the battalion headquarters detachment. Another first lieutenant would be Bn-2 or the intelligence officer. The regimental supply company would provide a Bn-4. The Board’s proposed battalion headquarters would also have 72 enlisted men, a substantial increase over what an AEF battalion would have had. Many of the extra men were assigned to a scout section and an observer section.[1] This represented a dramatic increase in the battalion’s tactical intelligence collection capabilities, an area in which the AEF battalions had been notably deficient.[2]

The Board also recommended that the staff of an infantry regiment expand from five officers to ten (plus three attached chaplains). It also proposed a much smaller regimental headquarters company with four officers and 183 men (without the pioneer, sapper-bomber, or one-pounder gun platoons). The regimental staff would include a munitions officer, a gas officer, and even a postal officer (prior to 1920 these did not exist below the division level).[3]

The Superior Board submitted its report in July 1919 but General Pershing was dissatisfied with its conclusions and did not release it for over a year. He concluded that the Board had done its work too soon after the close of hostilities and had allowed the special conditions that existed at the time to unduly influence its findings. Pershing believed that a division could not be larger than 20,000 men and still be mobile enough for future battlefields. He had been advocating a triangular division of 16,875 built around three infantry regiments plus a regiment of 75mm guns. Rifle companies would be of the AEF type but a battalion would have only three of them plus a machinegun company. The latter would increase to 250 men both to improve its mobility and to create a fourth machinegun platoon.

While the Superior Board’s report remained in limbo, the Army General Staff, in concert with officers from the Army Infantry School, had proposed its own division of 24,000 men. Like the Superior Board’s division, this one would have a square configuration (four infantry regiments). However, the heavy 155mm howitzers of the division artillery would be removed to corps command, and the infantry regiments themselves would be much more like General Pershing’s. Their battalions would each muster three 200-man rifle companies and one machinegun company.

Infantry School officers had pointed out that the infantry of any army must be considered its basic combat arm and that all other arms must be supportive of its requirements. Since a future war in which both sides enjoyed secure flanks, as in France, was considered unlikely, the Infantry School opined that in the future the infantry would operate by utilizing a combination of both position and open warfare. Thus, the firepower and staying power of a square division would still be needed even though tactical mobility would be more heavily stressed. However, a “slimmed down” square division could still retain adequate mobility despite the four-regiment structure. Nevertheless, Pershing stuck by his triangular division and attempts to resolve the differences between himself, the General Staff and the Infantry School failed. Therefore, Secretary of War Newton Baker intervened, set up a new board, called the Special Committee, and directed it to reach a solution.[4]

The Special Committee was generally composed of younger officers who had held key staff positions during the war, though it was headed by William Lassiter, a former division commander and member of the Superior Board. Another member was Captain George C. Marshall who, with Colonel Fox Conner, served as General Pershing’s representatives. The Special Committee met between 22 June and 8 July 1920 and conducted extensive studies and hearings. Testimony from about 70 officer witnesses led to the conclusion that the AEF division had indeed been too large. It nearly equaled the size of an army corps but its lack of a corresponding command structure seriously impaired its flexibility.

Discussion then focused on whether a future division should have a triangular or square structure. Although the Committee agreed that a future repetition of the recent fighting in France was unlikely, future enemies would still be deploying their forces in depth in both attack and defense just as the Germans had done. To defeat such opponents, a square division, which could deploy two infantry regiments forward and two back, was desirable. This left the question of whether a square division could conform to the 20,000-man limit advocated by General Pershing.

Brigadier General Hugh Drum proposed replacing the division machinegun battalion with a light tank company, cutting the size of the rifle and machinegun companies in the infantry regiments, and reducing the number of artillery and support troops. Mobility would still be inferior to that of a triangular division but sufficient for most situations. Although Pershing, Connor, and Marshall continued to press for a triangular division, they finally settled for the smaller square one. It totaled 19,997 officers and men, barely within Pershing’s upper limit.[5]

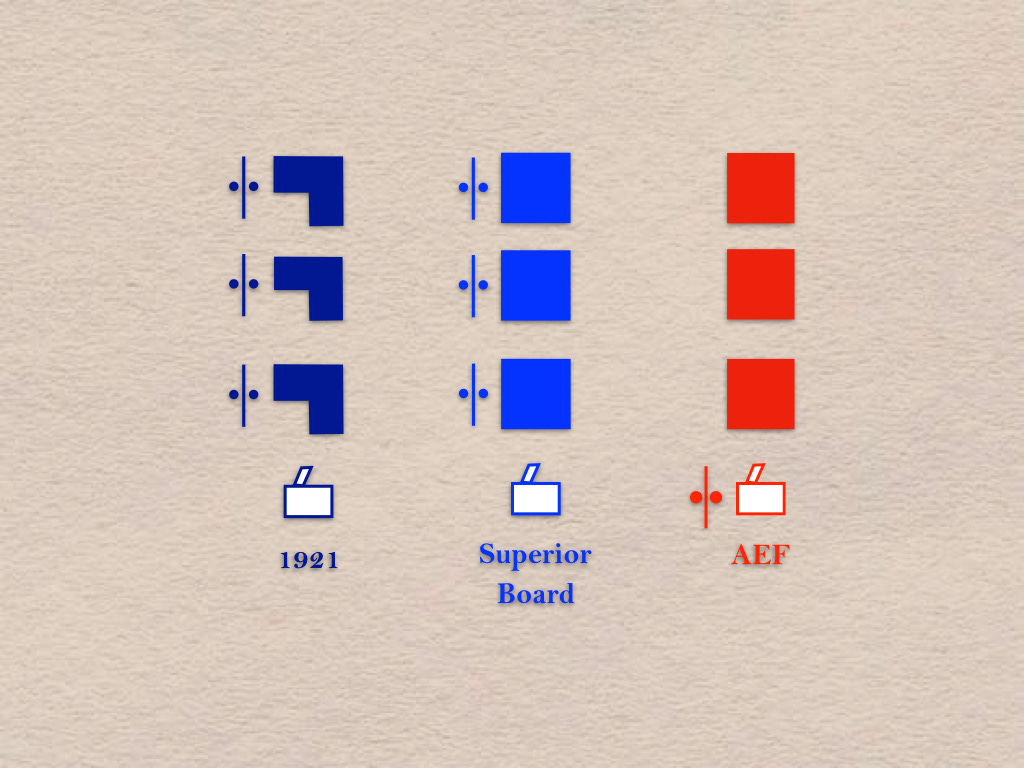

After considerable labor had been expended over the details, tables of organization for the new division were officially published on 15 April 1921. The infantry regiments became much more self-sufficient than in 1918 and incorporated all of their own machineguns and communications. Brigade machinegun battalions disappeared and the division signal battalion became a company. Other reductions in the division’s supply and transport elements saved enough manpower to form a labor unit (the division service company) that could take over many of the work details that the riflemen had to perform in the old AEF divisions. Service battalions operating at corps and army levels replaced the AEF pioneer regiments.

Although the new division had enough support units substantially reduce the time its infantry would have to spend on non-infantry tasks its infantry strength would be dramatically reduced. With only three rifle companies and three rifle platoons per company an infantry battalion in the 1921 division would have only nine rifle platoons vice the 16 in an AEF battalion. With two rifle companies forward and one back, a 1921 battalion could attack on a 400 to 800-yard front. Its defensive frontage would be about twice as great.[6]

Within the rifle platoons, uniformly organized sections and squads supplanted the old AEF “do-it-yourself” system of cobbling together tactical squads from dissimilar rifle, automatic rifle, hand bomber, and rifle grenadier sections. The War Department (and later the Chief of Infantry) undoubtedly hoped that the resulting simplification of the rifle platoon’s structure would make it much easier to command. A new multi-rolled rifle squad would be the basic fighting element. It was still the old Uptonian organization of a corporal and seven privates but it now had its own Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) and its own rifle grenadier (with a grenade launcher attached to his rifle). Despite its inaccuracy and slow rate of fire, the rifle grenade launcher was still the only weapon in the regiment, outside of the howitzer company, that could lob exploding projectiles into horizontally faced targets such as machinegun nests.

The BAR gave the new squad some much-needed automatic firepower. In keeping with the tactical importance of his weapon, the BAR gunner was rated as a T6 (Grade 6) “technician”, though he would probably rank as a PFC as well. Another man assisted the BAR gunner in carrying his ammunition and could take over his weapon if he became a casualty. Two of the squad’s riflemen were also trained as scouts. The senior private in the squad was trained to take over if the corporal became a casualty. For ammunition, the squad was supposed to carry 100 rounds per rifle and 480 for the BAR but it would normally receive additional ammunition just prior to entering combat.

Hand and rifle grenades would be issued as well but World War I experience showed that, despite their usefulness in action, grenades tended to be discarded by the already heavily laden troops. The troops had received little training in throwing the hand grenade and tended to lack an appreciation of its value. Three rifle squads, led by a sergeant and assisted by a corporal (serving as “guide”) made up a rifle section. This section replaced the old AEF “half-platoon.” Two sections plus a platoon leader, a platoon sergeant, and four runners comprised a rifle platoon.

While the new platoon’s six uniformly organized squads led by two section leaders constituted a great simplification of the AEF organization; they must still have been a handful to control. The usual platoon formation for movement or attack was a column of sections (one section following the other) with each section arranging its three squads in a line parallel to the enemy’s front and perpendicular to their own direction of movement. Alternatively, the sections could be arranged in line, each section’s three squads forming a “vee.” In this way, the platoon would have a four-squad front with two more squads in trace. For the squads themselves, two principal formations were recognized, a column for movement and a wedge or “vee” formation for combat.

This latter formation covered a front of 20 to 40 yards. The corporal would be in the lead with his BAR man directly behind him. Three riflemen would be echeloned to his left and three more to his right. When approaching the enemy, the rifle company would advance with two of its platoons forward and one back. As they drew nearer the enemy, the squads in the forward sections of the two forward platoons would then each detach a scout who, with the scouts from the other squads would form a six or eight-man skirmish line about 100 to 300 yards ahead of the company.[7]

The headquarters of a rifle company was somewhat larger than what it had been in the AEF though it functioned in much the same way. The company executive officer was present only in wartime and would continue to function more or less as the Baker Board had prescribed. Except for his principal task of ensuring that the company commander had an experienced and qualified successor, most of his duties were well within the competence of a good company first sergeant. However, unlike the French, German, and many other armies, the US Army did not consider a mere platoon leader as fit to take command of a company on short notice. The American reliance on executive officers was really an organizational solution to training/selection problems with platoon leaders and NCOs. In spite of this, the overall quality and training of American non-commissioned officer corps rose significantly after the war, though its responsibilities did not significantly increase.[8]

The number of enlisted men in the 1921 rifle company headquarters had increased since 1918 despite the fact that they were serving a smaller unit (see Appendix 3.1). They included six spare privates whose only purpose was to bring the company’s enlisted strength to 200. Neither personal weapons nor specific duties were officially assigned to these men although since companies rarely had all their enlisted men actually present and fit for duty, the question of how to employ “spare” men seldom arose. For combat, the Special Committee expected rifle company headquarters to operate as a captain’s group and a rear echelon, just as it had done in 1918.[9]

Although the fourth company in each 1921 infantry battalion was now a machinegun company it assumed the letter designation of the old rifle company that it had replaced. Thus, in a given regiment, Companies A, B, C, E, F, G, I, K, and L remained rifle companies while Companies D, H, and M became machinegun companies. Each of these machinegun companies, however, would have only two platoons.

This was aimed not so much at economizing on the company’s manpower as it was at increasing its mobility. The idea was to reduce the length of the battalion’s march column and, through this, that of its parent division. March column length had a direct impact on tactical mobility and flexibility. A short column could move on or off a road and bring all its elements into action much faster than a long column could. Due to its vehicles and animals, a machinegun platoon took up nearly the same road space as a rifle company.[10] Thus, cutting a machinegun platoon could significantly shorten a battalion’s march column and increase its tactical agility.

It was hoped that the mobility of the machineguns themselves could be further enhanced by the addition of two more ammunition bearers to each machinegun squad. However, the bulk of the machineguns’ ammunition would still have to move in the same heavy carts that the AEF had used. A machinegun company headquarters was similar to that of a rifle company except that in addition to an executive officer (authorized only in wartime) it included a reconnaissance officer and reconnaissance sergeant. The ammunition officer of 1918 was gone. His job did not really require a full-time officer (even in wartime). As in 1918 there was also a company train that included the company’s motorcycle messenger (T6) but no supply vehicles.[11]

Editor’s Note: The format of the many appendices to this work fit poorly with Substack. For that reason, I have placed them on a PDF file that can be found at Military Learning Library, a website that I maintain.

[1] The scout section was to have a sergeant, four corporals and 20 privates. The observer section would get a sergeant, two corporals and 12 privates. There was also a signal section of four sergeants, five corporals and 15 privates. This replaced the old telephone detail and the messengers, orderlies, and signalers that used to come from the AEF regimental headquarters company.

[2] “Extracts from the Infantry Board” op cit pp. 12-13.

[3] Ibid pp. 14-15.

[4] John B. Wilson, “Mobility Versus Firepower” op cit pp. 48-49; and Maj A W Lane, Gen Staff “Tables of Organization” pp. 486-487.

[5] Wilson op cit pp. 49-51; and A.W. Lane op cit pp. 487-491.

[6] Chief of Staff US Army Field Service Regulations (FSR) 1923 (Washington DC US Government Printing Office 1924) p. 80; this was the counterpart to today’s FM-100-5. It will be refered to below as FSR 1923.

[7] US Army “Tables of Organization - Infantry and Cavalry Divisions” Table 28 W, “Rifle Company, Infantry Regiment” 15 April 1921 (Ft Leavenworth Kansas, The General Service Schools Press 1922); see also Allan J. Greer, 5th Infantry, “Infantry Attack Formations” Infantry Journal February 1921 pp. 144-148; and Walter R. Wheeler USA The Infantry Battalion in Wat (Washington DC, The Infantry Journal Inc 1936) pp. 1-7.

[8] US Army “Tables of Organization” Table 28 W, “Rifle Company, Infantry Regiment” 15 April 1921 op cit; see also Gudmundsson interview op cit.

[9] US Army “Tables of Organization” Table 28 W, “Rifle Company, Infantry Regiment” 15 April 1921.

[10] If train vehicles are included (though all of these actually belonged to the supply or service company) the differences become less pronounced. A rifle company’s train vehicles (both combat and field trains) would approximately double its column length from 95 to 185 yards. A machinegun company’s train vehicles would increase its column length from 205 yards (90 yards for each platoon) to 315 yards. A full battalion would have a column length of 1,030 yards, of which all its combat and field trains would use 500 yards. See War Department Tables 26W “Infantry Battalion (War Strength),” 28W “Rifle Company, Infantry Regiment (War Strength)” and 29W “Machinegun Company (War Strength)” all dated 15 April 1921.

[11] US Army “Tables of Organization” Table 28 W, “Rifle Company, Infantry Regiment” 15 April 1921 and Table 29W, “Machinegun Company, Infantry Regiment” 15 April 1921 op cit.; see also “Notes From the Chief of Infantry - Three Platoon Machinegun Company” Infantry Journal August 1927 (Washington DC) pp. 177-179; For British machinegun practice see Dolf L. Goldsmith, The Grand Old Lady of No Man’s Land, The Vickers Machinegun (Cobourg, Collector Grade Pubs 1994) p. 93; and Wheeler op cit pp. 7-12.